As those within China and abroad continue to grapple with the coronavirus outbreak, artists like Shanghai-born, New York- and LA-based Duyi Han are attempting to apply a more creative and abstract skillset to the problem. Han, who studied architecture at Cornell and worked at architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron before settling into his current role as creative director of boutique studio Doesn’t Come Out, recently put out a striking series of images entitled “The Saints Wear White,” which he made “so that we have a subject to put our hope and faith in, and feel emotionally connected with, even if people don’t experience it physically yet.”

Han drew on his architectural training and self-declared creative focus on “the evolution of art, design, aesthetics, and the feeling of experiencing a perceptual environment” to create the murals, which digitally insert images of medical workers in gloves, masks, and full-body suits onto the walls and ceilings of a Christian church in Hubei province, the primary Covid-19 infection area.

“As an art form, church painting is powerful in invoking the emotion of respect and sublimity,” reads a press release for the project. “In Hubei Province and especially Wuhan, Western influence brought in churches and church art starting from the 19th century. In this context, Duyi Han chooses to use this religious architectural and art form to celebrate and advocate for secular life-savers. It is both locally relevant and globally understandable.”

RADII caught up with Han to talk about his method of conflating European architectural motifs with imagery intended to promote acknowledgement of the heroes on the front lines of Hubei’s medical crisis:

Duyi Han

RADII: Can you give a brief introduction to your design and architecture practice and your company, Doesn’t Come Out?

Duyi Han: My design philosophy, which is about the evolution of art, design, and aesthetics, is influenced by [the] Taoist belief that things always change, and by the mutation and fluctuation of historic European art movements. Our world is going from the “Baroque” to the “Rococo,” and I see styles and social sentiments changing constantly. My work transcends the limitation of style differences and looks at time and the change of Zeitgeist.

As a company, we don’t operate like conventional interior design studios or creative agencies — our job is to develop a set of design “algorithms” from our research, and we apply these “algorithms” to very diverse work of different styles, created by ourselves or in collaboration with other designers. So in a way we call ourselves a mutator who collaborates with designers to mutate their designs and create unforeseen work.

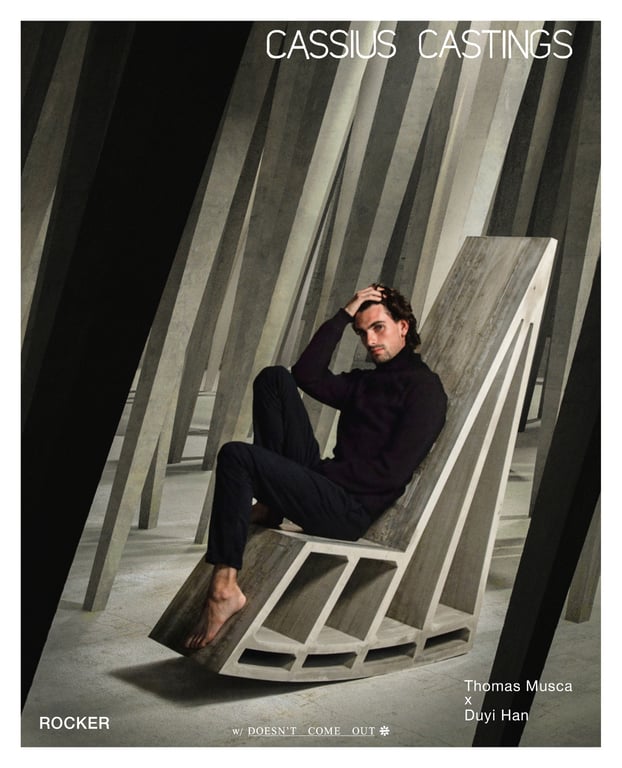

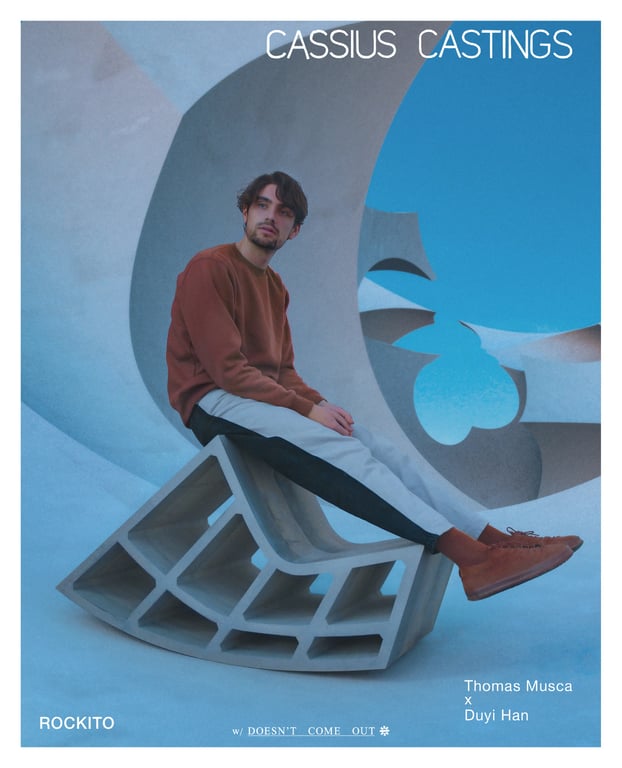

One example of our mutation work, which is also what I have been working on a lot in the past few months, is with Thomas Musca’s other studio Cassius Castings in LA — we made many pieces of concrete furniture together, and we’re planning to show at NY Design Week this May.

What was your motivation for making “The Saints Wear White,” a work celebrating and memorializing front-line medical workers combating the Covid-19 outbreak in the region?

What was your motivation for making “The Saints Wear White,” a work celebrating and memorializing front-line medical workers combating the Covid-19 outbreak in the region?

As the crisis is widespread, I’m concerned about the situation even when I am physically in the US now. Medical professionals in China deserve much better work conditions and public regard — I see recent media exposure of doctors beaten by desperate patients, doctors having to skip meals and sleep in hospital rooms, doctors running out of decontamination suits and having to share used suits or wear the same suit for a long day without using the restroom… I want to use my work to at least celebrate and advocate for them.

Artistically, many of my recent design experiments involve historic architecture and the sense of time and aging, and how to create work of contemporary aesthetics that invokes emotion. I think this chapel mural is one example.

Did you visit this chapel and physically paint this mural or was the image made digitally?

We intend to realize this mural and open it to the public as soon as we can, although we want to prevent cross-infection in a public space during the current situation of quarantine. But it is important to see this work now, and therefore I digitally visualized these photos, and I want them to feel absolutely real so that we have a subject to put our hope and faith in, and feel emotionally connected with, even if people don’t experience it physically yet.

I want them to feel absolutely real so that we have a subject to put our hope and faith in, and feel emotionally connected with, even if people don’t experience it physically yet.

As someone who lives and works primarily in the US, what has the been the main cultural reaction to the coronavirus outbreak in your observation? How do you hope to influence or inform this reaction with your work?

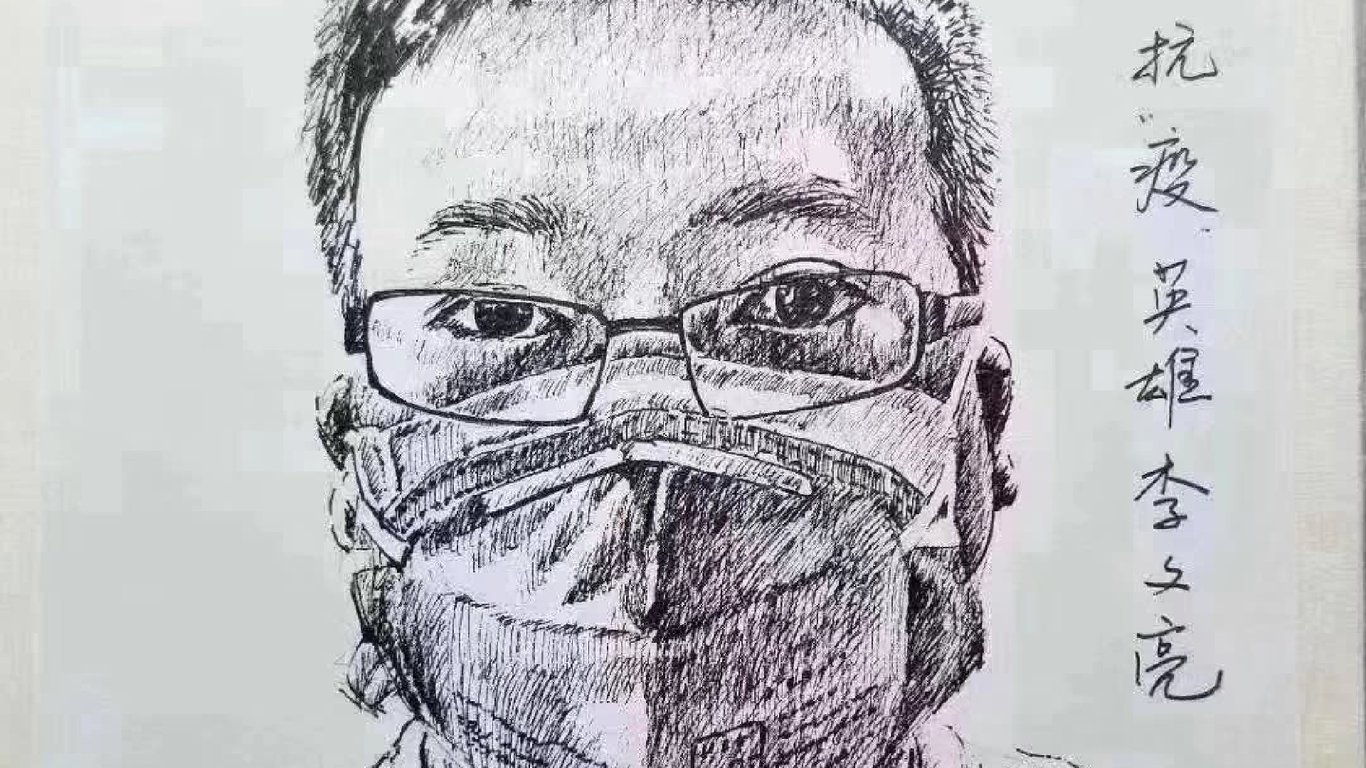

A lot of content that has been circulating on my Chinese social media feed is focused around three groups: desperate patients, hardworking medical workers, and government officials. Within the Chinese context, my work responds to the public sentiment towards medical workers, such as Doctor Li Wenliang. I have received many thank-yous from Chinese viewers.

Related:

Death of Coronavirus Whistleblower Doctor Li Wenliang Provokes Grief and AngerDr Li Wenliang’s death has sparked an outpouring of emotion in ChinaArticle Feb 07, 2020

Death of Coronavirus Whistleblower Doctor Li Wenliang Provokes Grief and AngerDr Li Wenliang’s death has sparked an outpouring of emotion in ChinaArticle Feb 07, 2020

In comparison, the reaction to coronavirus in the US is more tepid and sporadic. People are paying attention at different levels. I feel grateful that many of my friends have expressed care and people have been donating. On the other hand, I have heard words saying why the temporary hospital in Wuhan has bars on its windows and looks almost like a concentration camp. Of course there needs to be more understanding.

In general, people in China are doing their best. Because the US is geographically and culturally far from China, many people view the situation more simply, as if news from China is about the country as a whole. Perhaps if someone hears that an artist has created a mural of medical workers in China, they would automatically think that the murals are in some kind of Chinese-style building. In a way, having the murals in a church challenges stereotypical cultural assumption. Also, it is easily understandable to Western and global viewers because it is a church — so maybe it guides people to focus more on the content (medical workers) and not the country as an exotic entity.

Follow Duyi Han and Doesn’t Come Out on Instagram.

You might also like:

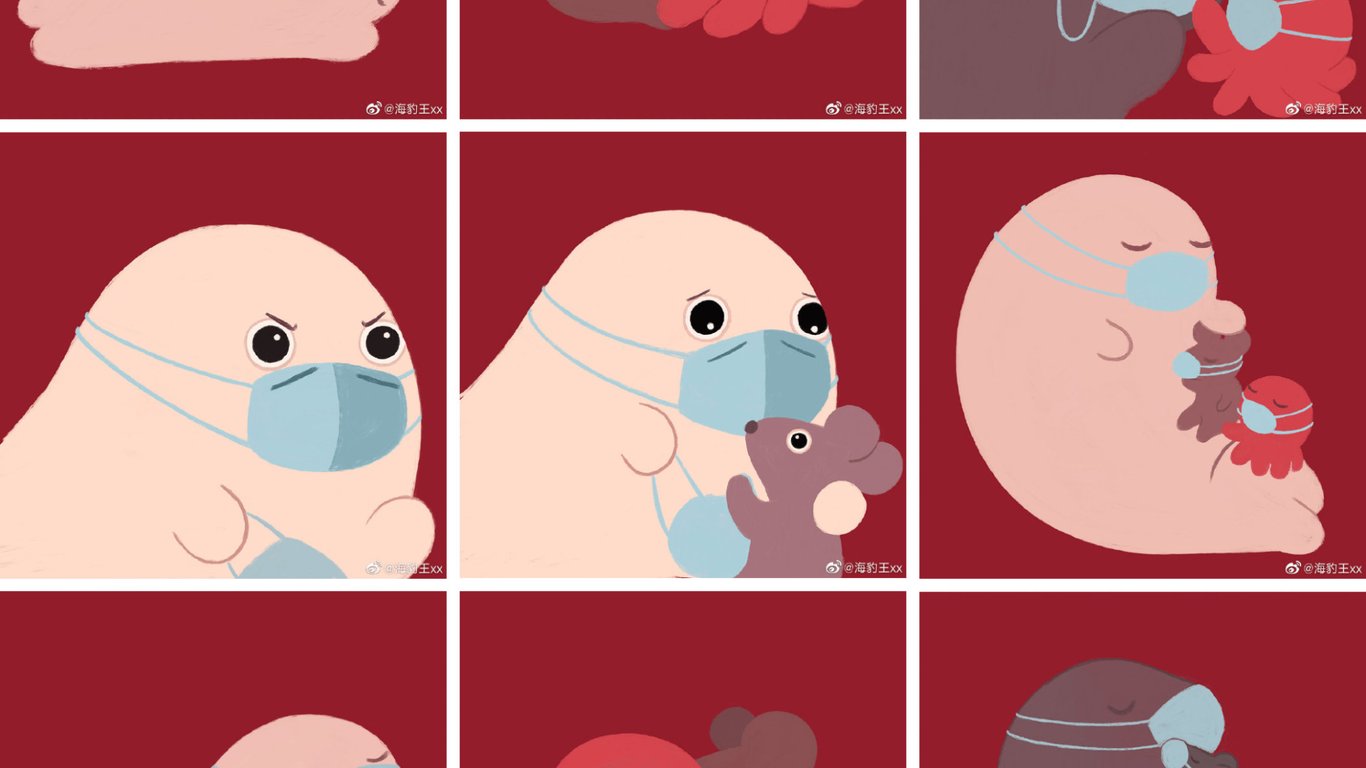

Chinese Cartoonists Grieve, Pray and Respond to the Coronavirus OutbreakIndependent cartoonists have responded to the epidemic, eschewing prosaic happy Year of the Rat illustrations in favor of decidedly more pointed and poignant worksArticle Feb 03, 2020

Chinese Cartoonists Grieve, Pray and Respond to the Coronavirus OutbreakIndependent cartoonists have responded to the epidemic, eschewing prosaic happy Year of the Rat illustrations in favor of decidedly more pointed and poignant worksArticle Feb 03, 2020

Wu Qingyu on Bridging “the Universal and the Specific” in her Bicultural DesignsArticle Jun 21, 2018

Wu Qingyu on Bridging “the Universal and the Specific” in her Bicultural DesignsArticle Jun 21, 2018