China’s massive online literature reservoir continues to grow, and, at the same time, continues to be underrepresented by traditional publication houses around the world.

There are exceptions, however, such as the proliferation of fan translations of Chinese literature, which can be easily found through a simple Google search.

At the dawn of the internet, many of these translations were of established authors, like Jin Yong, whose works are well-known but not available in English. However, as online fiction and the platforms that host them have grown in size and popularity, it is becoming easier to find English fan translations of contemporary Chinese popular fiction. These translations can be found on various platforms, like WordPress, Blogspot and, for many translation groups, on their own platforms.

Are You Addicted to Online Literature?

We spoke with two separate teams that took it upon themselves to translate Chai Jidan’s (柴鸡蛋) web novel Are You Addicted (你丫上瘾了), which go by the names Sae et al. and RosySpell. They spoke to us about their background, as well as some of the positive and negative aspects of the fan translation community.

Are You Addicted was originally serialized in 2013 on LCRead (连城读书) one of the biggest online platforms for literature in China. Divided into two volumes, the first focuses on the main characters’ youthful days in high school, and the second portrays the protagonists’ adult lives.

Related:

What’s Going Wrong with Chinese Literature in Translation?Chinese readers are often buying entirely different books to international readers of Chinese fiction – what’s going on?Article Oct 19, 2020

What’s Going Wrong with Chinese Literature in Translation?Chinese readers are often buying entirely different books to international readers of Chinese fiction – what’s going on?Article Oct 19, 2020

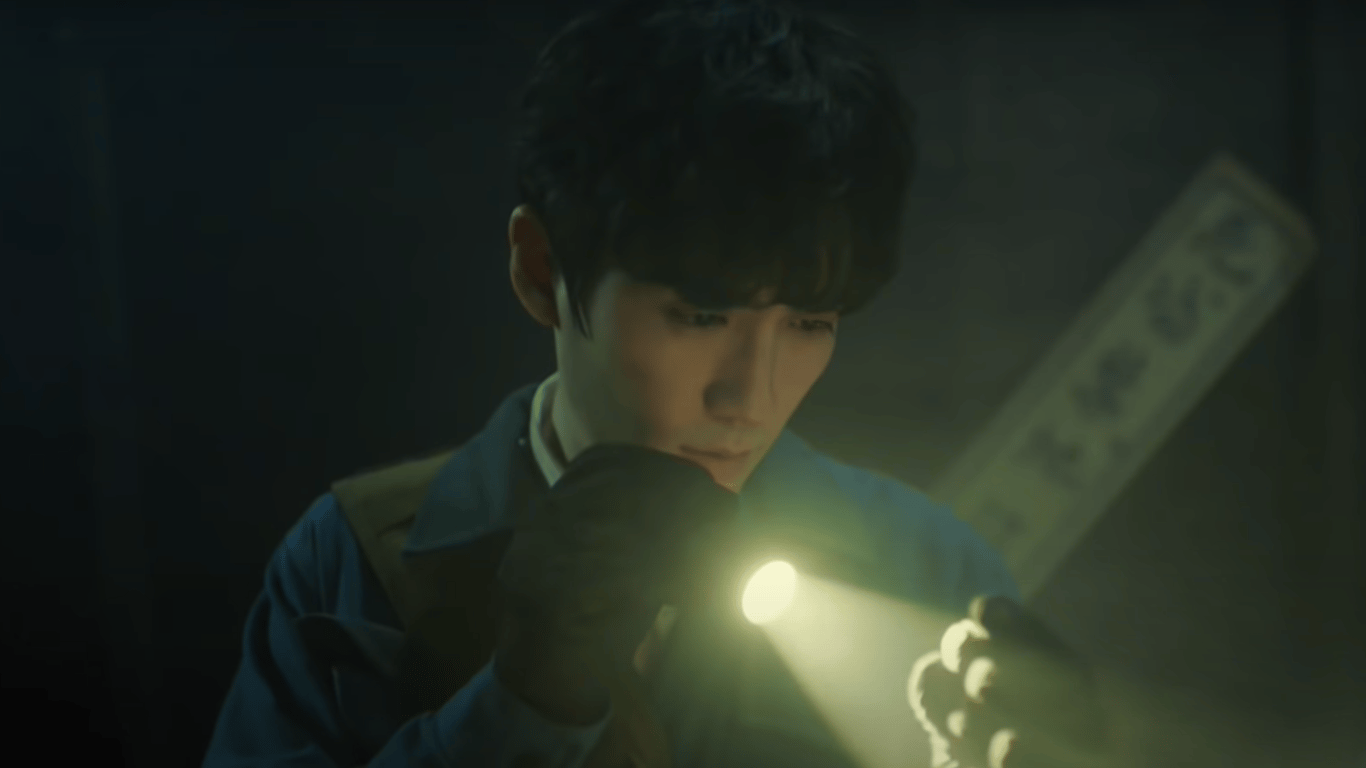

The web novel has been adapted into an audio drama and a web series, with the latter at the center of controversy due to its daring portrayals of homosexuality and its loyal re-representations of the plot. Chai Jidan also acted as a writer for the series, and she guaranteed her fans that a lot of the original work would remain unchanged in the adaptation.

The popularity of the series not only attracted the attention of viewers, but also the authorities. Only part of the first season was aired before it was abruptly pulled. While, it is unlikely that there will be a second season, the first season is actually available on Youtube, with censored and uncensored versions. While part of Addicted was aired, Chai Jidan’s other novel adaptation Advance Bravely (盛势), is only available on overseas platforms like Youtube and Dailymotion, and most likely will never be available in China (that show actually featured Gong Jun, star of Word of Honor).

Some of the translators from both teams mentioned that they became interested in the web series or audio drama before searching for the original literary works. Now that transmedia storytelling has become a norm in Chinese media, it is becoming more likely that audiences encounter visual adaptations before they learn about a novel.

As Jin Feng pointed out in her study of popular web romance, Romancing the Internet, this digital fictive realm has become a space for Chinese women to be creative, consume, share interests, and escape or cope with reality. What is unexpected is that these works have moved beyond national borders, and are influencing women in a Sinophone context.

Related:

Chinese Fanfiction is Entering Into (and Upsetting) the MainstreamThe world of Chinese fanfiction has been beset by murky copyright issues and high-profile controversies with real world consequences – can it continue to thrive online?Article Dec 10, 2020

Chinese Fanfiction is Entering Into (and Upsetting) the MainstreamThe world of Chinese fanfiction has been beset by murky copyright issues and high-profile controversies with real world consequences – can it continue to thrive online?Article Dec 10, 2020

Sae et al. is a team of three women, Sae from the US, Nancy from Australia, and Ana from Mexico. Sae and Nancy are the translators, and Ana is the proofreader, the only member who does not read or speak Chinese on this team. The three of them met online, and have kept in touch since they finished their translation project.

Sae is fluent in English, Khmer, and Mandarin Chinese. She is a native Khmer speaker and learned English when she moved to the US, and earned her B.A. in Chinese. She is also Cambodian-Chinese from her paternal grandfather’s side. Nancy moved to Australia from China when she was a child, and claims that she is not fluent in reading or speaking Chinese, but has managed to retain her listening skills through watching Chinese dramas. The most intriguing of the three is Ana, whose mother tongue is Spanish and who learned English in school. In addition to proofreading, she also translates Sae and Nancy’s version of the story into Spanish. Ana has a translation team of her own, one member from Mexico and another from Argentina.

Lost in Translation

Running the risk of having the original story get lost in translation is a constant battle for these translators. The complexity of the layers of translations from one language to another, then again from the second to the third languages, belies the difficulty of adapting these stories for different cultures. This is not limited to the wide differences between these languages and cultures, but also in that there are regional dialect variations of the original, second and third languages.

First of all, Are You Addicted is set in Beijing and a good amount of local dialect and slang appear throughout the novel. Secondly, when translating Chinese into English, not only is the Beijing dialect lost, there are also various regional differences in English. For example, American English differs somewhat from California to Alabama, but there are much greater differences between Australian English and South African English. While one can assume that Are You Addicted was translated with American and Australian English in mind because of Sae and Nancy’s background, it may not be obvious to the casual reader. Third, as Ana mentioned in her interview, she originally translated English into neutral Spanish. Yet she found it difficult to convey the novel’s sense of humor, idioms and slang in neutral Spanish, so she eventually decided to translate into Mexican Spanish, which some of her Spanish readers had difficulty understanding. Both teams mentioned that they had been asked by their readers for permission to translate their English versions into other languages.

Related:

Is Chinese TV Biased Against Non-Mandarin Music?Recent incidents on iQIYI’s major music variety shows have thrust so-called “dialect music” back into the spotlightArticle Aug 24, 2020

Is Chinese TV Biased Against Non-Mandarin Music?Recent incidents on iQIYI’s major music variety shows have thrust so-called “dialect music” back into the spotlightArticle Aug 24, 2020

RosySpell, on the other hand, is a team of two women, Rosy and Lavender who are both based in California. Both are Cantonese speakers that do not speak Mandarin Chinese, and claim that they are not fluent in reading Chinese. Both of them mentioned in the interview that they learned to read Chinese on their own or in college. They began translating because they were interested in reading Chinese novels, but would either be disappointed when translators stopped updating the story, or when they read poor translations. In order to prevent repeating the faults of other translators, Rosy and Lavender complete their translations before posting regularly.

Rules of Engagement

Since fan translations are unofficial, there are some unspoken rules and problems that plague the community. It is typically agreed upon that once a story is in the process of being translated, other people should not translate it.

However, both teams have different attitudes regarding this unspoken rule. While Sae et al. honor this rule because they understand how hard translators work on their stories, RosySpell pointed out that translators do not have ownership of the story. Since each translation will come out differently, it is up to the reader to decide which version they prefer. Both teams mentioned that they have frequent interaction with their readers, sometimes even changing segments of their translations due to reader suggestions. They have also experienced having their translations posted on other websites without their permission.

Related:

10 Great Works of Chinese Fiction to Read in the Age of CoronavirusFrom science fiction to classic romance, add these 10 Chinese fiction books to your reading listArticle Mar 31, 2020

10 Great Works of Chinese Fiction to Read in the Age of CoronavirusFrom science fiction to classic romance, add these 10 Chinese fiction books to your reading listArticle Mar 31, 2020

The interest and demand for Chinese popular literature, in particularly stories that focus on the Boys’ Love (BL) genre, is huge, and not just among English readers. And while this is the case, the gap to translate these works will unlikely be filled by traditional publishing houses or professional translators, but will remain in the unregulated realm of fan translators.

Cover image via Unsplash