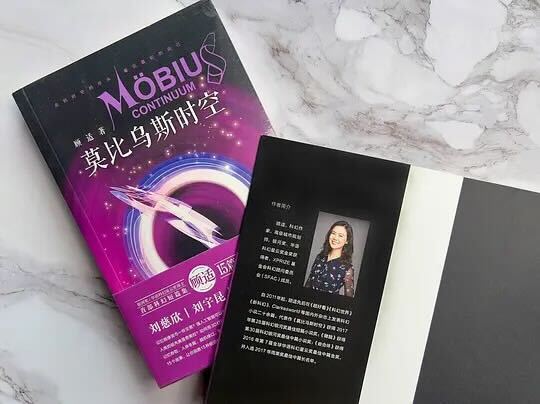

Gu Shi has stormed onto the sci-fi literary stage, captivating readers with her boundless imagination. As a speculative fiction maestro and a proud member of the China Writers Association, she’s racked up an impressive haul of accolades. Her mind-bending short stories have snagged two coveted Galaxy Awards for Chinese Science Fiction and a dazzling trio of Chinese Nebula (Xingyun) Awards. But here’s the twist—writing is just her side gig! Since 2012, she’s been cracking urban riddles as a researcher at the China Academy of Urban Planning and Design, diving into that world a mere year after she first unleashed her sci-fi brilliance on the page.

In her early years of writing, she instinctively defaulted to male protagonists. For those of her generation in China, most exposure to science fiction came from Western novels of the 1970s and ’80s, which overwhelmingly featured male leads and had few female characters. After her short story, Möbius Continuum, won the Galaxy Award in 2017, she received questions from English-speaking readers, many such as, “Why weren’t there any female characters in your novel?” That was her first moment of awakening to the power of her femininity.

In an interview with 36Kr, Gu reflected that this perspective might stem from her own upbringing. Her mother comes from a family of many sisters, where women take the lead in organizing and coordinating family gatherings. Even her grandmother on her father’s side was a college graduate—an uncommon achievement for women of her generation. The remarkable capabilities of these women gave them the authority to make critical family decisions.

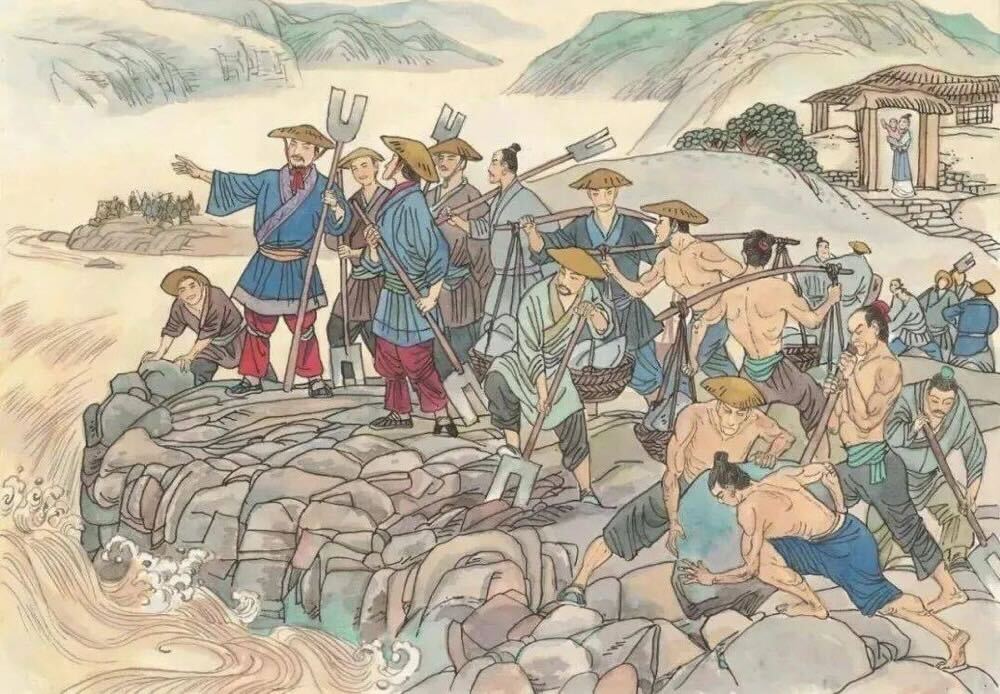

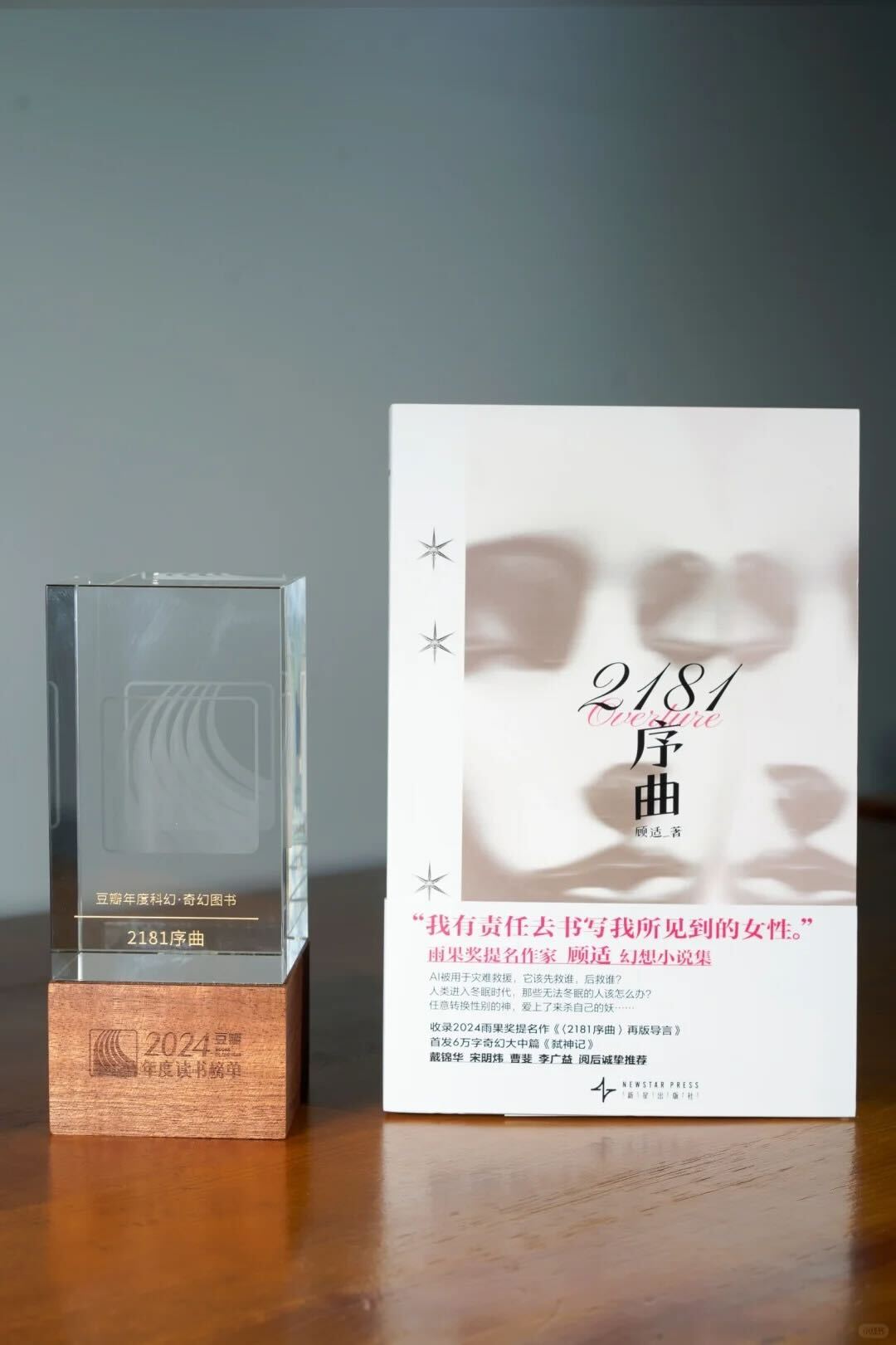

Another transformation in Gu’s writing came when her work began reaching an international audience. Some foreign readers wondered why they couldn’t sense a distinct “Chineseness” in her stories. In her early works, like Möbius Continuum, she still mimicked elements from classic Western sci-fi. However, by the time she wrote City of Choice, she had already begun exploring her own perspective—connecting the theme of rising sea levels to the legend of Dayu. In her latest short story collection, 2181 Overture, she found a balance between preserving her Chinese identity and maintaining a universal appeal. Students at New York University, who studied her work in their course readings, noted that her stories “could happen in Beijing but also in New York.” The narratives and themes resonate across cultures with equal impact.

Of course, Gu has faced dilemmas and struggles in expressing her intersecting identities. In her story, Killing the God, from her latest collection, the two protagonists fluidly shift between genders due to their supernatural powers. Their gender identities remain ambiguous in the early chapters, later challenging stereotypes. Rooted in Chinese mythology, the story still allows these characters to bear children. Some critics argue that this remains within traditional gender norms and the conventional division of labor. However, Gu is undeterred by such critiques. She believes that each work can only address certain themes, and if she were to fixate on negative feedback about what she didn’t challenge, it would only hold her back.

Gu Shi has consistently advocated for a more diverse creative landscape for women. Drawing from her background as an urban planner and designer, she has a natural ability to construct new worlds from the ground up. While researching for her novel, City of Choice, she realized that the ancient legend of Dayu, who controlled China’s great floods, made no mention of his female family members. How did his wife raise the next ruler of China while Dayu was preoccupied with water management? The only plausible answer, she thought, was a matriarchal society. When considering how sci-fi can influence the real world, Gu points to The Handmaid’s Tale as an example. “After that book came out, people became aware that we must never let reality resemble The Handmaid’s Tale,” she explains.

“Whenever real-life developments even slightly resemble it, people immediately recognize the warning signs.” She recalls a conversation with sci-fi critic San Feng, who once told her, “The world didn’t become cyberpunk precisely because cyberpunk was written.” Science fiction can serve as a low-cost way to present possible futures—if people realize that an undesirable future is approaching, they may actively resist it. For Gu Shi, her feminist storytelling is a fortunate part of this broader movement.

Cover image via Sohu.