Ask Shanghainese multimedia artist Frank Wang Yefeng, and he would know everything about renting a llama in the state of Illinois. He had one standing outside the exhibition hall for his graduation show at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The animal is a popular attraction at kids’ parties in the United States, but it wasn’t a good idea to have it out on the street.

“I spent a couple of thousand dollars on it, and, after an hour or so, the Chicago Police showed up and detained the llama,” Wang says. “They said it needed a working permit.”

Until authorities inflicted the anthropocentric rule upon the poor llama, the animal was the performative element of Wang’s graduation piece. It related directly to a digital installation inside the building, establishing a conversation between the virtual and the real worlds.

The llama also alluded to the internet meme ‘Grass Mud Horse,’ homophonous with ‘fuck your mother’ in Chinese, which is a creature of the Chinese internet that looks like a llama — or an alpaca, if we want to be exact. The meme became part of the internet lexicon around the time of Wang’s graduation in 2011, used to protest censorship in China.

The llama pop-up in downtown Chicago. Image courtesy of Wang

Criticism disguised as humor is one of the key aspects of Wang’s art. Working in the intersection of video art, writing, and technology, he explores profound subjects like belonging, othering, and racism in seemingly nonsensical 3D sculptures and animations that feature a whole menagerie of bizarre non-human creatures.

Although they may seem goofy and laughable initially, these creatures embody his philosophical views on human existence and the “in-betweenness” that exists within us all.

Fifteen years after moving to the United States, Wang, now New York-based, still muses on his experience as an immigrant and the sense of estrangement that never faded. “Since arriving in America, I have always had this strong sense of the absence of a home and origin. Whenever I went back to China, it didn’t feel like going back home at all. I felt like a tourist. But in the United States, I’ll always be an outsider,” he says.

However, instead of regretting his extrinsic position, Wang chose to extract inspiration from it. “I began thinking of this groundless, in-between space as my constant dwelling and decided to enjoy it and explore subjectivity from it,” he says.

Bird-themed street art in New York. Image courtesy of Wang

Such an enduring sense of flux became clearer in Wang’s art through his experimental portrayals of birds, a theme that came to him as he roamed his neighborhood in New York.

“West Harlem has a lot of people of color and a lot of immigrants. One day I was walking around the neighborhood and noticed that all the graffiti in the streets showed birds. I thought it was bizarre at first, but then I started to link things in my head. Birds are migratory animals; graffiti is a gesture of freedom. It’s all symbolic,” he says.

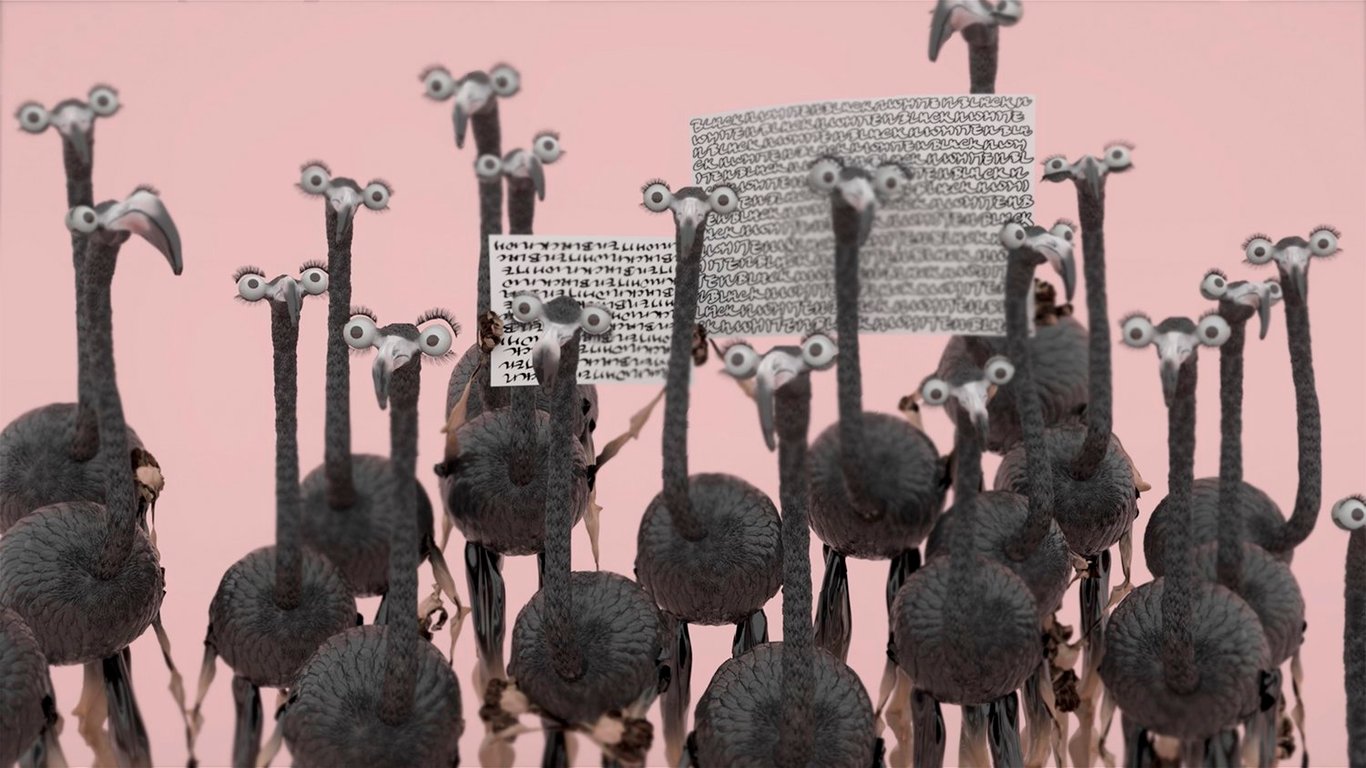

Since then, Wang began collecting photos of these birds and writing poetry inspired by them. In the series of animations BIRDS Volume I, he converts them into his own characters: a mallard adrift in the sea, a group of protesting flamingos, an American eagle in TSA uniform, and a group of sparrows — all registered in post-modernist art ideas.

Wang combines these strange beings with his poetic musings on migration, including revealing verses such as “direction is an obscure assumption” and “departing is to find new ways of arriving.”

To Wang, home is not a physical location but an ontological position.

“You’re constantly surrounded by different ideologies. This migration is not only physical but also on your mind.”

— Frank Wang Yefeng

Wang expands on the notion of direction as something irrational in Moscow Has Nice Weather, an infinite loop showing a twisted plane spinning over a flight map. He devised this piece while being literally ‘in-between,’ flying from China to Germany for an art residency in Berlin.

“On the plane, I was thinking about how uncertainty goes against the way our human brain works. So I started writing these short poems and using my phone to record the screen in front of me,” he says.

In this piece, Wang wanted to reject any form of rationalism. Inspired by the poster of the 1980 blockbuster Airplane!, he modeled his 3D version of an Aeroflot aircraft, albeit twisted as if it didn’t know where it was going.

As timing would have it, he landed in Berlin right at the beginning of the pandemic, when quarantine rules were strict. His lockdown experience in an unknown city resulted in The House of the Solitary, a series combining his poems with 3D models of his surrounding objects.

By then, Wang was already drawn to theories of object-oriented ontology, which, in sum, say that non-human entities maintain independent relations and importance beyond our human-centric perspectives. In other words, your toaster has something to say — even if you can’t hear it.

The House of the Solitary at Vanguard Gallery Shanghai. Image courtesy of Vanguard Gallery Shanghai

“I was stuck with these objects, and they were stuck with me. So, I started transforming them into my virtual characters. It’s almost as if they carry my emotions,” Wang says.

He created slow-motion 3D clips with the objects constantly being inflated and deflated. Though it might appear that these objects will explode sometime, they never do. Tellingly, the soundtrack to these videos is made of background hold music — the type people have to deal with when calling airlines.

Wang had several flight cancellations while in Germany, and his intended three-month stint in the country extended into seven.

Once restrictions eased, he went on what he calls a “discursive” road trip, avoiding highways and driving through secondary roads with no planned itinerary. One day, near the border with the Czech Republic, while passing by a run-down roadside cafe, he noticed the statue of a bird standing in front of it.

“It was making a bizarre gesture, waving at you, trying to make a connection. But the cars were just driving by and ignoring it. The bird was almost like a specter in the middle of the street,” Wang says.

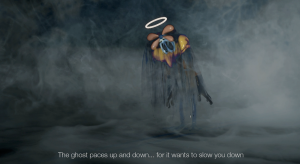

The animated bird inspired by the statue Wang saw during his road trip through Germany

Wang reclaimed the image of this bird and rendered it into an animation clip, BIRDS Volume II — Slow Spectre. In it, the bird first appears in a dark vacuum, waving incessantly at the viewer with a plastic smile and dizzy eyes. Then it appears as a ghost, semi-transparent, under a dark see-through veil. Finally, it contorts itself and melts.

“With my birds series, I was contemplating the ambivalent position and the existential condition of ‘others’ in our society. They’re almost like ghosts: they see everything around them, but they are never seen,” Wang explains. When asked who the ‘others’ are, he says, “immigrants, minorities, you name it. Literally, anyone who’s not Anglo-Saxon.”

Back in New York, with the rise of hate crimes against Asians, Wang was invited to create art for a public screening event in Times Square. He had already been working in public art and thinking of how public spaces can enhance dialogues among different people.

Based on post-humanism concepts, he conceived The Whimsical Characters, an ongoing series of digital bodies made of objects he found online. These characters were displayed on large screens, juxtaposed with stop Asian hate slogans, such as “exotic is not a place” and “not model minorities, listen to our stories.”

Like the bird on the German-Czech border, his Times Square characters continuously attempt to connect with people passing by.

Interestingly, despite their outlandish appearance, their emotions are pretty much real. Wang applied motion capture technology based on natural human behavior to enhance their emotional appeal — the result is rather haunting, especially with a heart-shaped character that weeps desperately.

“Since I used real intense human emotional data, these characters also exist somewhere in between virtual and real. They live in an ambiguous dimension,” Wang explains.

This year, Wang has been exploring the notion of the ‘yellow peril’ that has permeated Asian diasporas in the West for more than a century, notably through the Eurocentric representation of East Asians as a threat to the white world. Among many very unflattering portrayals, the one he finds more outrageous is the association between East Asians with a grotesque, evil octopus reaching its tentacles to seize wealth in Western countries.

Once more, he reclaimed the image of this loathsome octopus and turned it into the central theme for The Levitating Perils, a series aiming to highlight the century-old racist rhetoric and deconstruct harmful Eurocentric notions about East Asians that still prevail today.

“I think it has never been gone,” Wang says about Asian hate.

“But it happens in much subtler ways today, which can be more dangerous. In recent years, not just because of the pandemic, but because of the change in the international order, everything is worse,” he goes on, adding that the rise of China as a superpower threatens Western hegemony and the world’s unipolar dynamics.

“Naturally, all this gets projected into society,” says Wang. “I rarely talk much about politics, but since you asked,” he adds.

Still, Wang says that he’s not pointing fingers. The goal of his octopus series — and his art as a whole — is to deconstruct harmful beliefs and shift fixed ways of thinking toward more open-ended angles and possibilities.

Through his journeys and explorations, and in his constant in-betweenness, he establishes something special: the development of his art in a continuous process of dissimilation and re-framing.

Additional reporting by Lucas Tinoco

Cover image courtesy of Vanguard Gallery Shanghai