This post by Bernd Gartner was originally published on the blog Wanderlust Beijing. It has been edited and re-posted here with permission.

The grey skies stirred and wind beat against the windows of my office. Suddenly it started to snow, and I watched the flakes of white ice whipping around outside. I’d brought my Eisenhower jacket, and I was about to travel south to Zhengzhou for Qingmingjie (清明节), also known as Tomb Sweeping Day. My hands and ears were a bit frosty as I walked to the subway, headed to Beijing West Railway Station.

As it would turn out, this trip was to be all about jiaozi (饺子), dumplings usually filled with both ground meat and vegetables. Jiaozi are serious business in China, usually eaten on special occasions like the Spring Festival. Jiaozi are a symbol of family and the holidays, and making them is a way for families to bond during the celebrations.

They also happen to taste pretty damn good.

Related:

Photo of the Day: Qingming (Tomb Sweeping) Festival is this WeekArticle Apr 02, 2018

Photo of the Day: Qingming (Tomb Sweeping) Festival is this WeekArticle Apr 02, 2018

There are lots of stories about the origin of jiaozi. One version tells of how Zhang Zhongjing, a famous Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) practitioner, used jiaozi to treat frostbitten ears. He found that poor nourishment and insufficient warm clothing in winter caused many patients to suffer from frostbitten ears. He used dough to make small thin pancakes, called “skin”, and filled them with his special recipe filling made of lamb, pepper and herbs. He boiled these small packets and gave the jiaozi and broth to his patients prior to Chinese New Year. To this day, Chinese people still have the tradition of eating jiaozi on the winter solstice (冬至, dongzhi) to avoid the ears freezing and falling off.

At university here in Beijing my friends started calling me “Mr. Jiaozi,” after watching me eat jiaozi nearly every day – not needing the special occasion to have my favorite dish. I was also living on a scholarship, so my budget for lunch was about 10 RMB (about $1.50 USD). Few things are as amazing in life as jiaozi with lots of vinegar and chili. A simple meal, and hardy like a Beijing taxi driver.

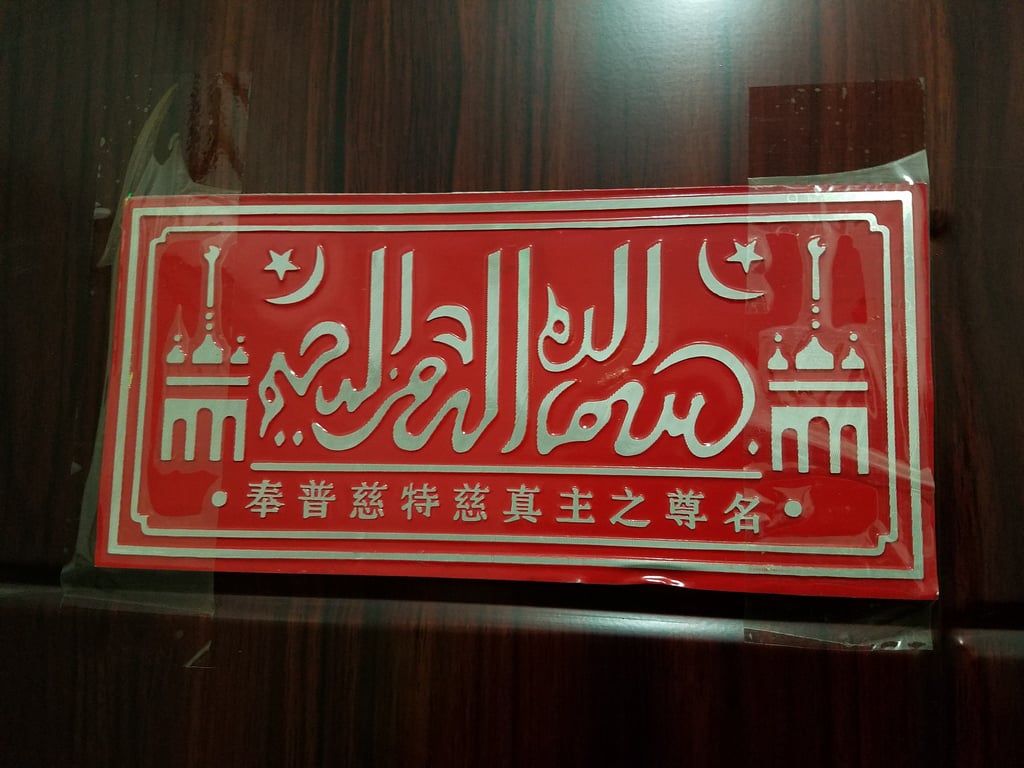

Arabic signage means you’re probably going to be eating lamb

I was on my way to Zhengzhou to spend time with my Hui family. Hui (回族) are one of China’s 55 ethnic minority groups, and practice the Muslim faith. For this reason pork, which is the filling for most jiaozi in China, is off the menu. So I was about to try a new type of jiaozi, and a slightly different experience.

Jiaozi filling, ready to go

And then there was dough.

A large piece of dough is rolled into a long log, and then cut into small pieces with a cleaver. These pieces are then pressed flat and covered in flour. The next person put the “skin” on their upturned hand, cupping it slightly before adding a lump of lamb and jiucai (韭菜) vegetable filling onto the skin. The skin is then deftly folded around the filling and sealed, creating a lamb-filled packet which looks a bit like an ear if done correctly. The jiaozi are then put on a large mat called a bi (箅), waiting to be cooked.

Apart from the skin and the filling, the other essential matter is the sauce you use to dip your jiaozi in. The sauce we had was a mixture of vinegar, soy sauce, chili oil and garlic. The quality of these ingredients makes a big difference to the final experience.

These dumplings were boiled jiaozi, known as shuijiao (水饺), literally meaning “water dumplings.” The bowl was placed in the center and we all sat down for dinner. The jiaozi were much chewier than usual, as the skin was much thicker than those I’d had before. The skin was almost like thick huimian noodles (烩面). The lamb itself was very good quality, like the lamb back in South Africa and Namibia. The dip was just the cherry on top — an explosion of flavors.

Apart from hulatang (糊辣汤) and huimian, the Longmen Grottoes (龙门石窟), White Horse Temple (白马寺) and some other sights, I’ll remember lamb jiaozi whenever I think of Zhengzhou.

Life is like a jiaozi restaurant

It can steam, boil or fry you

Although your skin might become crispy or even soft

You will end up stronger

Cover photo: Pippy Eats

You might also like:

Lessons from a 100-Year-Old Shanghainese WomanArticle Feb 07, 2018

Lessons from a 100-Year-Old Shanghainese WomanArticle Feb 07, 2018

11 Mouth-Watering “Real” Chinese FoodsArticle Jun 26, 2017

11 Mouth-Watering “Real” Chinese FoodsArticle Jun 26, 2017