Trigger warning: this article contains graphic descriptions of bullying and sexual violence.

Three months after seeing Yang Zhefen’s play Fade Away at the Wuzhen Theatre Festival, I can still hear the audience’s weeping cutting through the darkness just after the lights went out.

The play is a deeply affecting portrayal of the social issue of bullying and violence in schools, a topic that has become increasingly visible on Chinese social media in recent years. The play begins with the bully’s murder before immediately flashing back to an earlier, much more pleasant scene: three girls share an umbrella and get milk tea together after school, the kind of shared experience that has formed the foundation of many a friendship.

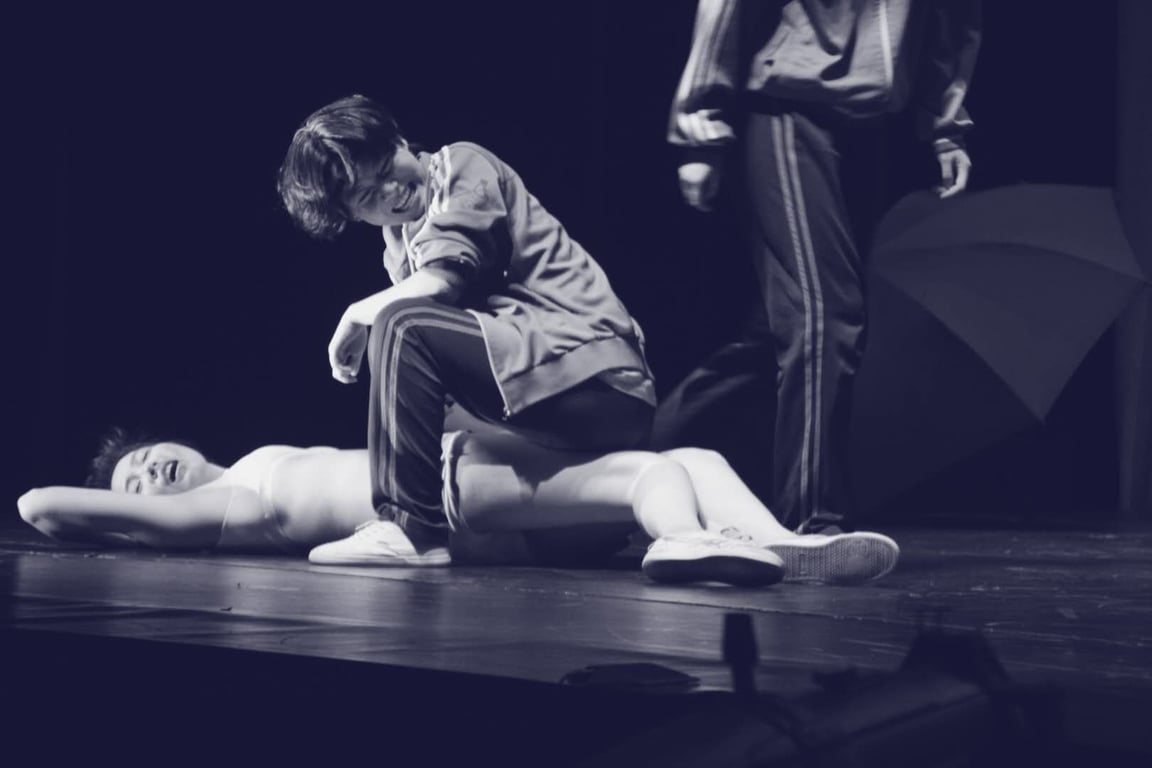

A scene from Yang Zhefen’s play Fade Away (photo courtesy 喆·艺术工作室 Zart Studio)

When the bullying begins, it starts small, with cruel words and a pin placed on a chair — but it escalates dramatically from there. The climax of the play is brutal to behold: one girl, suspected of having told a teacher about the pin on the chair, is set upon by three others, slapped around, burned with cigarettes, and, finally, stripped to her underwear and raped with an umbrella.

One would like to think that portraying something so gruesome took some creative license, but as recently as the second week of 2019, an 8-year-old girl in northwestern Gansu province was beaten up and violated with a broomstick by two of her classmates. (Yang’s play premiered in 2017 in Wuzhen, where it won the grand prize at the festival’s annual competition for young playwrights.)

Related:

Wuzhen Theatre Festival Brings Fringe-Style Performances to an Ancient Canal TownArticle Oct 24, 2018

Wuzhen Theatre Festival Brings Fringe-Style Performances to an Ancient Canal TownArticle Oct 24, 2018

Chinese netizens were understandably furious about the incident in Gansu, but this was one of countless such stories in the media. News outlets can only cover a fraction of such stories, and the public can only read about so many of them. How many times do we scroll past headlines like this in our own social media feeds? Addressing such an immense social issue is no small feat, and it’s easy to ignore the exact nature of the details in favor of retaining only a basic understanding of the fact that the social issue exists.

Playwright Yang Zhefen, center (photo courtesy 喆·艺术工作室 Zart Studio)

This is precisely why Yang did not shy from depicting the full extent of the bullying onstage. Asked why it’s important to put such graphic violence before the eyes of the audience, she replied: “People whose lives are under the light maybe never know, after all, just how dark those dark places are…. [I]n a certain corner of the world you don’t know, an incident of school bullying is happening ten or a hundred times crueler than what was in the play.”

Yang’s inspiration to write and direct the play was derived in part from an incident from her college years. Noticing a dorm room ajar one morning, she knocked to check if someone was inside, and was greeted with the grim sight of an underclassman lying in bed wearing a nightgown with bloodstains in the buttocks area. Yang says she was stupefied by the sight, and that the memory is still shocking. “I basically couldn’t distinguish her facial features, her whole head was so swollen… I think her tears were not able to flow out, just seep out of the cracks.”

In the aftermath, it came out that four other girls had ganged up on her the night before, because one of the perpetrators suspected that the victim was trying to seduce her boyfriend. The event was, briefly, a sensation at the school, but in the end nothing happened — the school recorded the incident, but did not punish the attackers, and even allowed them to continue living in the dorms.

In a stroke of brilliance, the same actresses who play the schoolgirls also play each other’s mothers. As painful as it is to witness the trauma of their home lives, there is a quality of sweetness in the way Yang attempts to direct the audience’s attention to the cyclical nature of pain. We all hurt each other, she seems to say — parents hurt children, who hurt other children, who are also being hurt by their parents. Those children later become parents who hurt their own children.

So, where does it end?

The opening scene of Fade Away depicts the victim murdering the main bully in the street — the rest is a flashback. This, too is strategic: had the play ended with a murder, there may have been some indication that this was a note of finality, a tragic heroine reclaiming her honor. What the audience gets instead, right before the lights shut off, is the victim alone onstage, bloodied face turned up and staring into the audience’s souls, pleading, accusing: “Why didn’t you save me? Why didn’t any of you save me? Why didn’t anyone come and save me? Why didn’t anyone come and save me…”

With an uncomfortable prickle, the audience begins to understand that they are, in a sense, complicit in the crime.

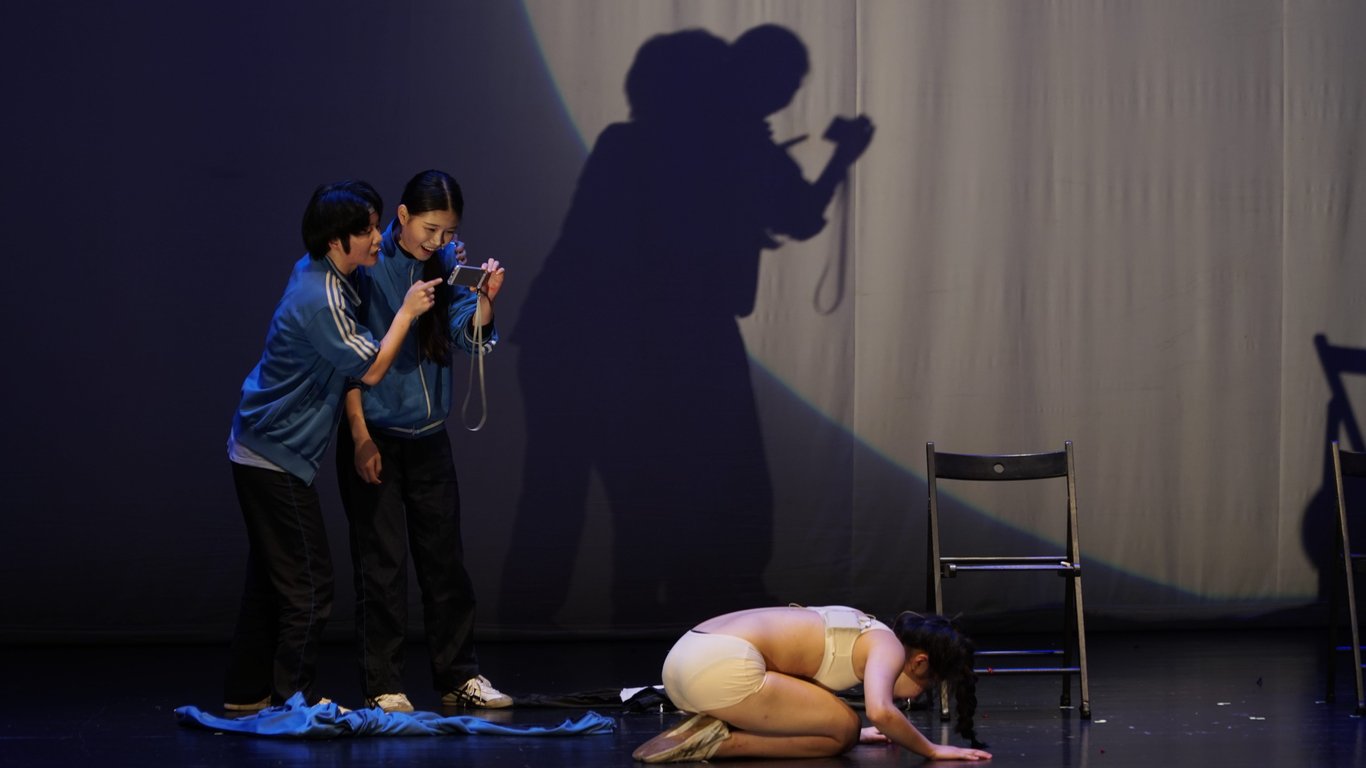

But according to Yang, this character is “the embodiment of not being self-aware.” Handed a phone, she films the initial beating; when ordered to grab one of the girl’s legs in preparation for the rape, she hesitates, but does it anyway, perhaps fearing retribution if she does not assist.

A comparison is drawn, then, between sitting and watching this spectacle within a play and the willful ignorance within our daily lives of the frequency and brutality of such spectacles. Silence and reluctance are complacency, and complacency allows the pain and the violence to continue.

As she falls silent in turn, the other actors file onto the stage and face the audience. Behind them, a montage of dozens of Chinese videos depicting youths being beaten, harassed, and bullied by their peers begins to play, clips all culled from social media and news reports. With a shock, the audience begins to realize exactly how real the events just witnessed on stage truly are. (A simple search of relevant keywords on Baidu or Weibo will indeed yield hundreds of thousands of articles.)

A scene from Yang Zhefen’s play Fade Away (photo courtesy 喆·艺术工作室 Zart Studio)

It would be easy for such a work to come across as preachy or pushy, but Yang and her actresses managed to avoid that tone. It is enough to have left an impression. It is enough that those under the light may now have seen even a fraction of the darkness, and it is enough to know that they will not forget it. Yang’s only real hope for the audience is that if they are faced with such a thing in the future, next time they will not simply overlook it. “Drama may not change society,” she says, “but within the scope of my ability, let more people see my work, let people think, let them be touched; this is what I am able to do.”

—

Cover photo: a scene from Yang Zhefen’s play Fade Away (photo courtesy 喆·艺术工作室 Zart Studio)