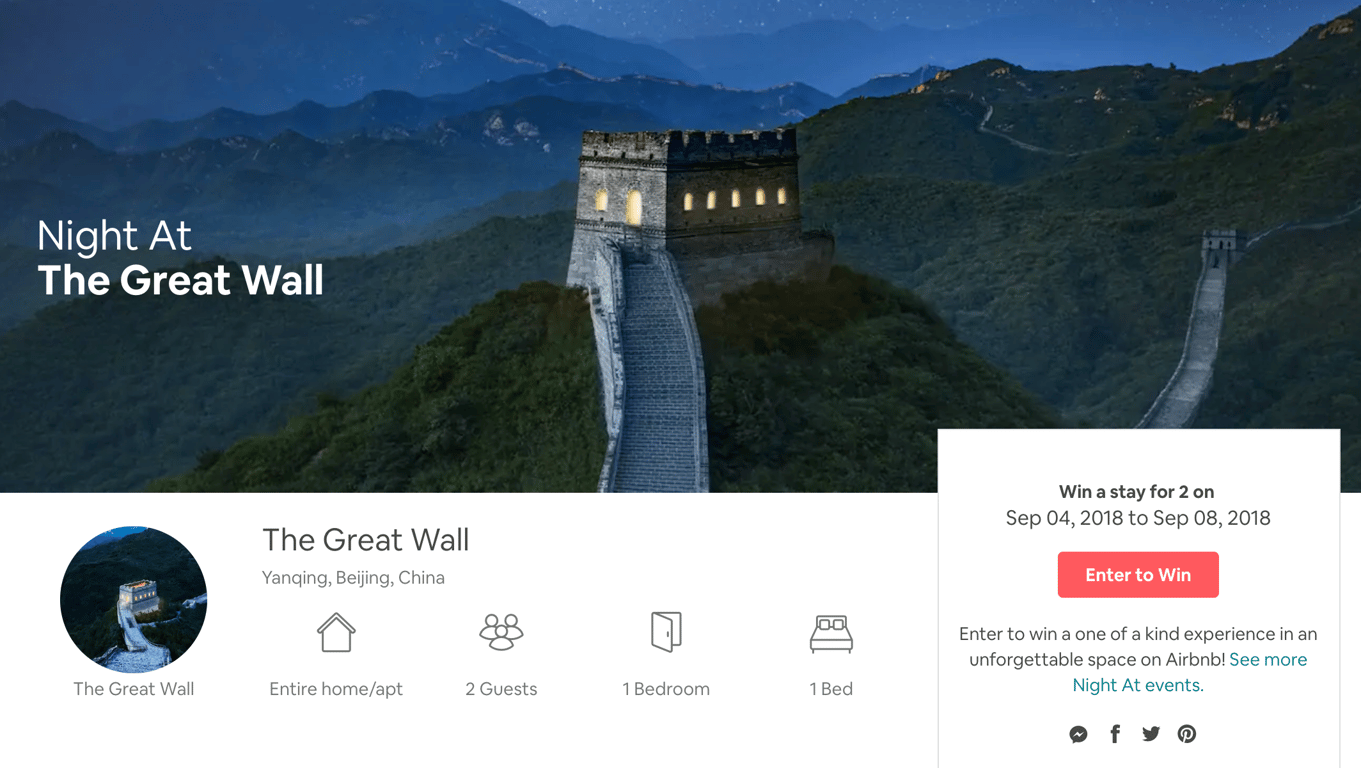

About nine years ago, a few friends of mine had the idea of leading hikes and camping trips up to one of the unrestored — i.e. “wild” — sections of the Great Wall, called Jiankou. Translated as “Arrow’s Nock,” it’s located north of Beijing, built on jagged cliffs and ridges during the late years of the Ming Dynasty in the 17th century. Due to its steepness and the fact that many parts are in disrepair, it attracts far fewer visitors than other parts of the Wall, such as the tourist-friendly Mutianyu section about six miles to the east. I went with them once, navigating precipitous stairs overlooking mountains and valleys and taking in some of the most breathtaking scenery Beijing has to offer.

Of course, it was also dangerous. Not too long before our trip, a couple of hikers had died there, leading villagers to caution all passersby. This part of the Wall has never been officially “open” to the public. Although what that actually means isn’t exactly clear, what is true is that Jiankou isn’t for everybody, certainly not the old or young who would, for instance, have trouble going up or down these stairs at a 75-degree incline:

I wonder if all that will soon change, thanks to restorations happening as we speak.

Reuters published a story yesterday called Rebuilding the Great Wall of China, featuring several stunning photographs of local efforts — which began in 2005 — to restore Jiankou. I know what you’re thinking: they’re going to ruin it. But I’m willing to withhold judgment for now: reportedly, only basic tools are being used, such as chisels, hammers, pickaxes and shovels, and pack mules are employed to transport bricks that are made to “exacting specifications.”

“We have to stick to the original format, the original material and the original craftsmanship, so that we can better preserve the historical and cultural values,” said Cheng Yongmao, the engineer leading Jiankou’s restoration.

Cheng, 61, who has repaired 17 km (11 miles) of the Great Wall since 2003, belongs to the 16th generation in a long line of traditional brick makers.

It’s possible that the government has learned from past mistakes. Just last year, for instance —

Authorities in the northeastern province of Liaoning, home to a 700-year-old section of the wall, paved its ramparts with sand and cement, resulting in what critics said looked more like a pedestrian pavement.

Soon after those disastrous repairs, the State Administration of Cultural Heritage said it would investigate any improperly executed wall preservation projects.

Of course, if this goes as planned, Jiankou will no longer be the quiet, remote site whose desolate beauty so impressed me when I visited in 2009. Tourists will come, you can bet on that (as they have in increasing numbers every year since the start of my friends’ now-defunct business). I’m not exactly dismayed, because in China good things are never kept secret for long. But I am growing a little wistful.

Rebuilding the Great Wall of China [Reuters] … the pictures above are all mine.