Kalman Pool doesn’t like rules, limitations, or boundaries. He wants no compass to guide his work or a single medium to define his art. He doesn’t even wish to be held back by the fundamental law of gravity.

Pool follows the Kantian philosophy that art can exist free from any subject, form, or content, independent from the wishes of society — in a separate universe altogether.

And a separate universe, indeed, he creates. A place populated by amebic mutants of enormous dimensions and bright, sometimes fluorescent colors. He makes them with no defined shape across paintings, ceramics, VR, and inflatable sculptures.

Kalman Pool’s 3D, VR-created piece “Duo”

Their oddity is often self-evident: many are one-eyed creatures or conjoined beings — mutations he learned about online. But, sometimes, they’re entirely abstract, making it difficult for us to identify any of their parts without a good stretch of the imagination.

At only 25, Pool’s art has already been exhibited in galleries from Chicago to Shanghai, including highly prestigious institutions like the Saatchi Gallery in London, known for launching the career of several young talents.

He was also a resident at the Swatch Art Peace Hotel and was invited to design his own limited edition set of watches. Still, he can’t help but look at his peers’ success with competitive eyes and feel like he’s yet to be entirely accepted by the art market.

Kalman Pool’s solo exhibition Unbearable Lightness

Pool’s competitive ethos traces its roots to his upbringing. He grew up in Guangzhou, not particularly focused on art but devoting most of his time to the sport of badminton, training with an athlete’s level of commitment, even as a kid. But he didn’t like the fact that he didn’t invariably win all games.

Things changed when he bought his first camera and began to photograph his surroundings and play with the digital manipulation of images. In art, as opposed to sports, he felt he had some edge.

“That’s how I realized maybe art was a game I could win. I felt that as long as I could spare some effort, I would create great things,” he says.

After graduating from high school in China, Pool briefly lived in New York City, studying photography at the Parsons School of Design. But, disappointed by the school’s emphasis on fashion and overall lack of creative vibrancy, he dropped out.

Kalman Pool’s “Luminous Opera36”

Pool’s time in New York wasn’t wasted, though. He was a frequent visitor of MoMa — the city’s famed Museum of Modern Art.

“When I saw the works of Pollock and Rothko, and when I learned about abstract expressionism, it blew my mind. There are no rules at all, and I realized art could be this free. I thought if they could do it, maybe I could too,” Pool tells RADII.

With time on his hands, Kalman traveled extensively across the United States. In Chicago, he learned about the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and how it provides remarkable freedom for artistic development.

“It’s really an avant-garde place. They don’t even grade your work. That’s why I went there to start over,” he says.

Kalman Pool

Pool graduated in 2019 with a bachelor’s in fine arts. He tried almost all different media types at the institute, from painting to ceramic sculpture and VR.

The unrestrained environment drove him to create new languages, forms, and creatures across different media.

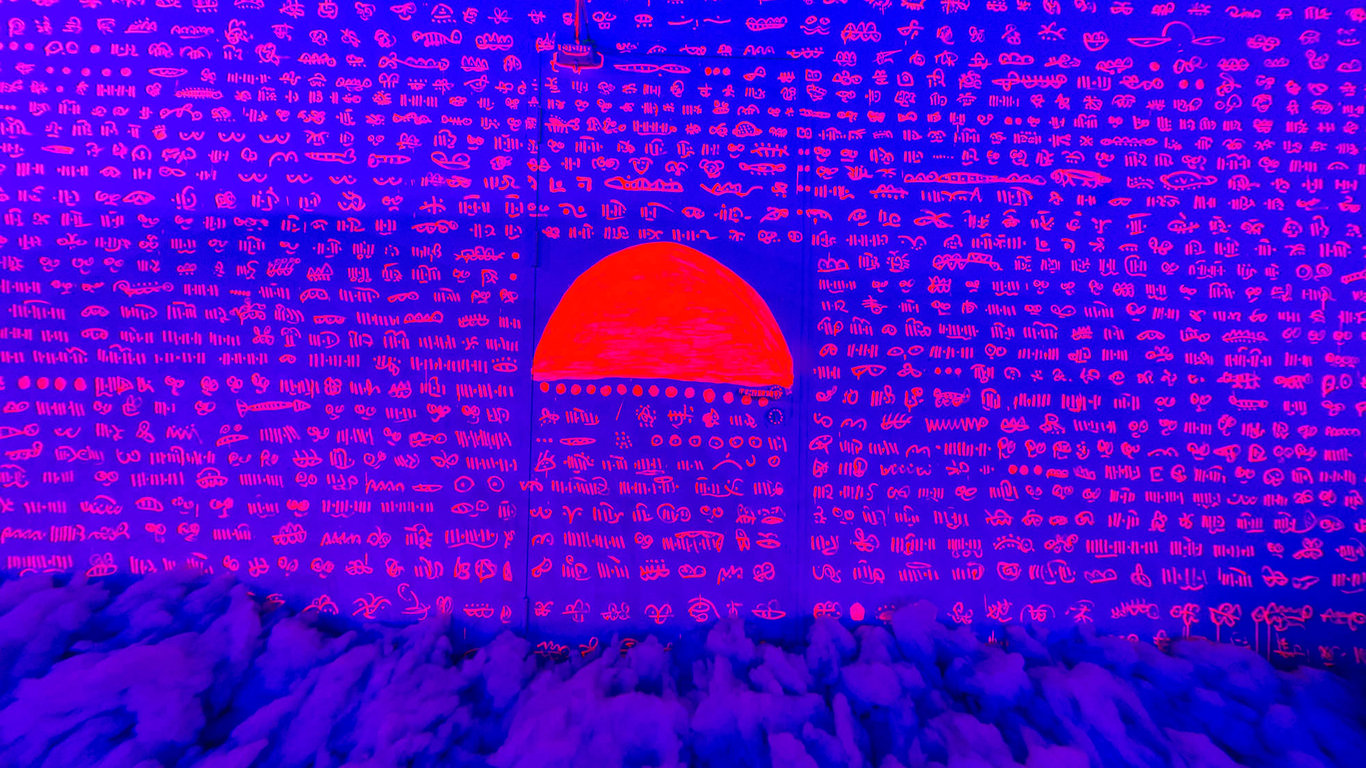

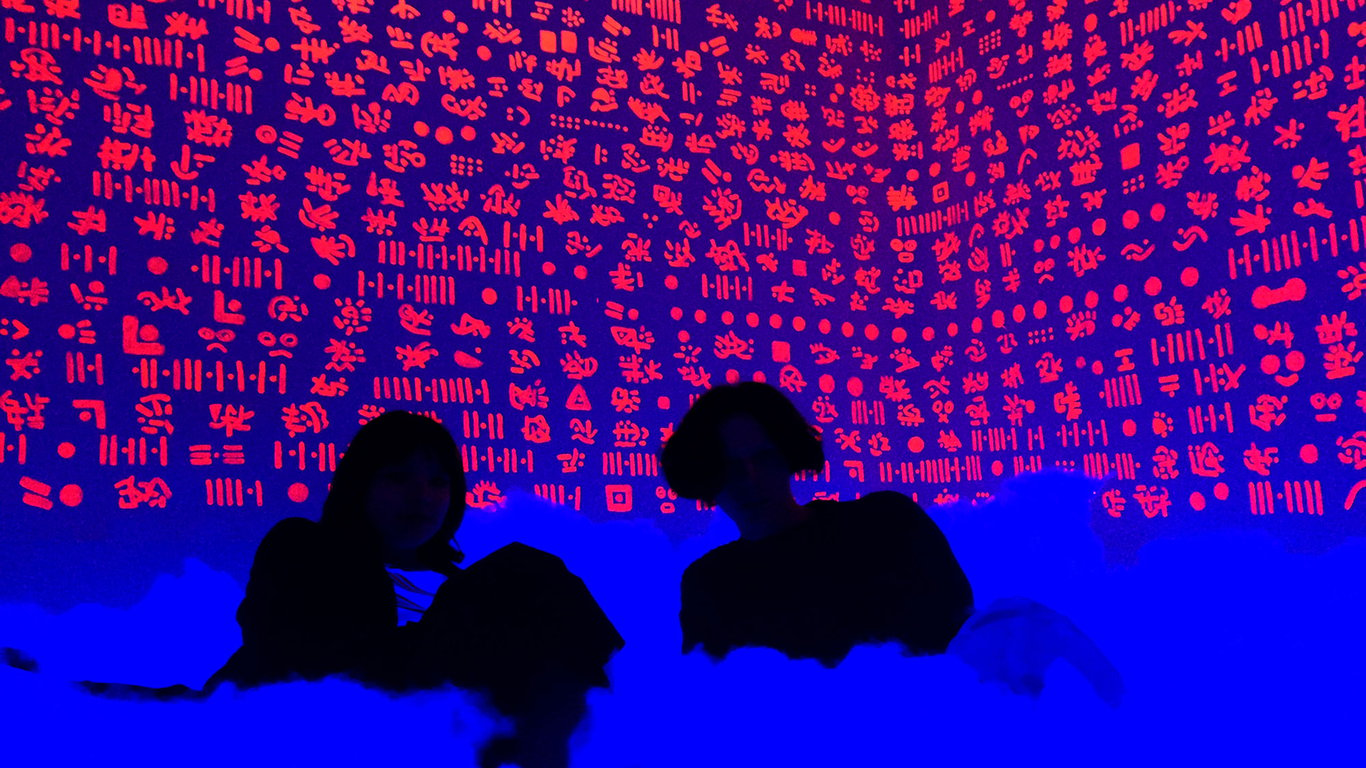

An iconic work from that time is “Under Heaven,” a gigantic site-specific fluorescent installation for which he created a unique communication code composed of symbols that only made sense to him. The installation was reproduced on a larger scale at the Coutts Art Center in Shanghai in 2020.

Kalman Pool’s “Under Heaven”

Chicago didn’t come without its share of traumas, though. Pool’s relationship with his then-partner became rocky, with intense arguments that occasionally culminated in physical violence. Amid the conflict, over 30 pieces of his work were destroyed.

This experience echoed in his art — particularly the ceramic sculptures, which Pool feels are almost abstract self-portraits in the form of traumatized, futuristic beings.

Struck by the loss of so many pieces, he turned to 3D sculpting as a safer way to create art. “I thought that if I created something digital, it would stay forever stored on the cloud, and no one could destroy it,” he says.

Even in the digital realm, Pool wanted to get his hands dirty, so VR was his medium of choice.

“Lion King” by Kalman Pool

The process of VR sculpting doesn’t start with a basic shape, such as a sphere or a cube, as flat CGI modeling usually does. Instead, Kalman uses a hand controller to draw in the air while wearing his headset.

He likens the feeling to holding an airbrush or a whipped cream gun. He squeezes a trigger on the controller to create any shape he wants with three-dimensional gestures — up and down, forward and backward, just as he would in manual sculpting.

But to him, VR is not about reproducing real-life experience — it’s about transcending it entirely.

“With regular sculpture, you’re limited by gravity, whereas VR is a space with no gravity at all, and you can create things that are impossible to do in the real world,” he says.

Along with several tools, the software provides seemingly endless color options and even a copy-paste command to replicate forms seamlessly.

Kalman Pool’s “A Desperate Possibility of Impossibility”

Another benefit of VR that Pool is particularly fond of is its portability. Unlike traditional sculpture, there are no materials or heavy tools to carry. All he needs is his computer and his headset.

“I like the idea of a mobile studio, and that I only need a small space to work. I can create in Europe, in America, in China — anywhere,” Pool says.

In seeking to free his outlandish VR creatures and bring them to our dimension, Pool landed on inflatables as the perfect physical medium.

“There are only three ways to output a 3D model: 3D printing, casting, and inflatables. Most people would think about the first two,” he says, but he chose the latter.

Inflatable art pieces designed by Kalman Pool

While studying for a master’s in painting at the Royal College of Art in London, his dissertation thesis was on inflatable sculptures.

He learned how the American military deployed an army of inflatable rubber tanks, trucks, and airplanes to deceive and disorient the Nazis, and how designers, advertisers, and artists, including famed American painter Ellsworth Kelly, were crucial in creating the illusion tricks for such classified missions.

After the war, when plastic became widely available, inflatable art gained some traction. First was Andy Warhol’s “Silver Clouds” in the late 1960s, an installation of metallic balloons filled with helium that reacted to people’s presence and motion.

A decade later came Jeff Koons with his readymade inflatable toys, all bought at discount prices in New York City and then arranged against mirror tiles to become art sculptures in galleries.

More recently, there was Florentijn Hofman’s “Rubber Duck,” a giant inflatable toy duck that traveled the world and arrived at Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbor in 2013.

Kalman Pool’s inflatable “Lion King”

Inflatables carried the properties Pool needed to persist in his unleashed experimentations. Air-filled forms are less limited by gravity, making it easier to play with scale and lightness.

Pool explores these properties to the fullest. His sculptures can be as large as three meters tall, and he often suspends them from the ceiling with transparent wires to make them seem indifferent to gravity, just as they are in the VR environment where they’re created.

Flexible PVC, the material of choice for his sculptures, is light and easy to color in the most brilliant, artificial tones.

Just like the dummy artillery from WWII, inflatable sculptures are highly portable. Pool’s enormous beasts can be rapidly transported worldwide for only a minimal shipping fee and inflated on-site in a matter of minutes.

That makes international exhibitions much more manageable. “It took 20 minutes to inflate the M4 tank,” he says.

Inflatable installations by Kalman Pool

Production is also fairly straightforward: Pool only needs to email his digital files to the manufacturer, who then engineers the structure.

Interestingly, he doesn’t create his sculptures to be inflated — such a purpose would only impose restrictions, and he wants to be free to create.

Hence, not even 10% of his sculptures are manufactured. Most remain in the digital realm, awaiting further improvements in inflatable technology.

“After the inflatables are manufactured, you have to think about the installation and the process of taking good care of them,” Pool says.

“My inflatable sculptures are silted. They have no fan blowing air. So they are fragile. They don’t break, but they deflate all the time.”

Just as it happened with “Rubber Duck,” exhibiting his sculptures worldwide over the years, Pool estimates that at least half of them deflated on-site.

“Melancholic Hot Air”

Recently, one deflated in Switzerland, and the gallery called him with a tone of desperation. “I told them to be patient,” he laughs. “You need to spend time with it. Listen to it. Touch it. Look through all the parts to find the leaking.”

Pool says it sometimes takes up to two hours to find the leaking point. He used to get angry and complain to the manufacturers about quality, but then he learned that cracking and leaking issues with PVC material are inevitable.

He now sees it as a way for him to connect with his artwork on a different level and to develop an intimate and tactile relationship with it.

“To me, inflatable sculptures have a life, and maybe they are leaking to tell me something,” he says.

Pool is now in Shenzhen for a residency at the Jupiter Art Museum, a private, non-profit institution promoting Chinese contemporary art.

The place is enormous and located in a former warehouse. But his studio, a few floors up, is not that large. It has no electricity or running water and is unfinished, exhibiting only concrete floors and walls.

Nevertheless, it’s a suitable spot for him to work on his ongoing series of paintings called Nocturnal Animals.

“Chengzi” by Kalman Pool

They depict his usual colorful creatures, but with a twist: they glow in the dark, and when you throw the UV light at them, their eyes pop. It feels as if you’re walking into their territory.

“It can get a little frightening here. But I enjoy it,” Pool says. His creatures don’t spook him, even if they come from a place of trauma.

In 2022, Kalman has lots ahead of him: a group show in London in late January, his residency wrap-up show in Shenzhen in June, and, possibly, a show in Milan this summer.

Few 25-year-olds recently graduated from art school have a comparable agenda. But Pool is demanding of himself, and he has big dreams.

He plans to create a public sculpture somewhere, like the ones he saw in Chicago, to reproduce the actual scale of his work in the digital world, where they can be as tall as buildings.

“Public sculpture can be very tall and overwhelming,” he says. Unsurprisingly, public art is another way for him to transcend limits. After all, he believes “there are no human limits in art. You can make the impossible possible — art is absolute and infinite.”

New works by Kalman Pool, including paintings and inflatable sculptures, will be shown from January 29 as part of a group exhibition presented by Berntson Bhattacharjee at the Pump House Gallery in Battersea Park in London.

Additional reporting by Lucas Tinoco. All images courtesy of Kalman Pool