Graffiti in the rubble of the Uyghur migrant neighborhood of Heijia Shan, or Black Shell Mountain, after it became the site of urban cleansing in 2014.

~

The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia is a biweekly column focusing on emerging forms of Uyghur, Han and Kazakh art and politics in the expansive region of China’s Northwest frontier with Central Asia and Russia – currently referred to in Chinese as the “New Dominion,” or Xinjiang. This column seeks to give voice to Xinjiang artists, filmmakers, writers, musicians and poets.

~

I first came to Xinjiang in 2001. At the time I was in the second year of an undergraduate program in photojournalism in my home state of Ohio. As part of my training I had the opportunity to travel throughout China, from Shenyang to Lhasa. It gave me a chance to try to understand the breadth and diversity of the space and get a feel for a profession and a country that would have a large impact on my life. Eventually I ended up in Kashgar. I had never seen anything like it: vibrant street life, warm and embracing friendships, a vibrant folk music scene, desert landscapes and Sufi shrines. The history of the place felt alive and vivid, but also fragile. It was also the only place in China where Han taxi drivers assumed I, a white German-American, was a local Uyghur. That misrecognition was instructive.

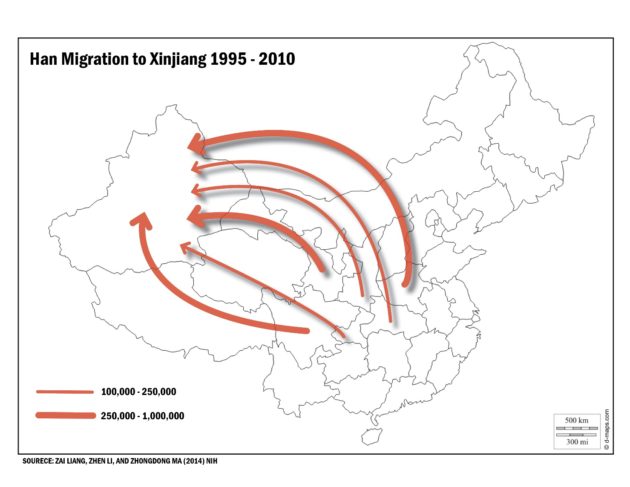

After I returned to the States and began studying the history of China and Central Asia in earnest, I came to understand that although this region had long been associated, to varying degrees, with China, Pakistan and Central Asia, the proportion of Han settlers did not reach more than ten percent of Xinjiang’s population until the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Since then, the number of Han migrants and settlers in the region has grown to nearly 10 million, producing a feeling of “occupation” among some native Uyghur and Kazakh inhabitants; at the same time, these settlers from Henan, Anhui, Sichuan, Gansu and elsewhere now also call this province home and feel as though they are playing a vital role in strengthening the nation.

Over the past two decades Xinjiang has become one of the primary destinations of internal Han migration

During years of language training in Chinese and Uyghur and fieldwork in Xinjiang, it became clear to me that over the past two decades, hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs have been displaced by the state-facilitated development of industrial farming, coal and oil extraction, and urban construction. As wealth accrues in the hands of a small number of Uyghur officials and an emerging class of Han settlers, tens of thousands of young Uyghurs are leaving their villages for a new life in urban centers. In new oil cities, such as Ürümchi, many of them struggle to find low-waged jobs in the food, service and retail industries, while at the same time dodging widespread harassment from urban police and urban cleansing projects put in motion after the violence of July 5, 2009. Kazakhs too are coming to the city in increasing numbers, as the state attempts to control their ability to earn a livelihood as herders in the north. In addition, Han migrants are arriving and taking up lucrative housing development and infrastructure jobs that are denied to Uyghur and Kazakh workers. The long-term research project I developed out of my growing interest in Northwest China addressed this contentious environment by considering how Uyghur, Kazakh and Han urbanites strive to narrate their futures and maintain a sense of stability when confronted with conflict.

~

Neither dominant Western media discourses of political violence nor official Chinese descriptions of “harmonious” modern development adequately address the lived experience and cultural life of people in Xinjiang. By highlighting Uyghur, Kazakh and Han cultural practices and objects, this column will strive to demonstrate the skillful ways in which marginalized people work out meaning in their lives.

Throughout the years I spent in Xinjiang and my ongoing visits to the region, two themes have emerged as critical in amplifying the voices of native Uyghur and Kazakh artists and Han migrant voices and visions.

First, there exists a politics of representation that consistently works against the community’s efforts to be heard and understood. On the one hand, artistic visions are often co-opted by the state and used to promote a patriotic Chinese agenda that simultaneously ignores the precariousness of marginalized people and makes them the target of blame when violence occurs. On the other hand, creative voices are overwhelmed by a focus on human rights abuses and narratives of victimization and terrorism in accounts from non-Chinese media.

Behind the scenes during the production of a Uyghur film in Ürümchi, 2015

Second, my partners in Xinjiang have identified the need to situate the contemporary arts scene in the context of history, culture and place. In order to shift the discourse away from the “peaceful development” of ethnic solidarity (from Chinese state media) and oppressive violence (from non-Chinese media) toward the work of living and making meaning in the midst of social precariousness, it is necessary to amplify autonomous narratives that arise from the work of Uyghur and Han artists.

This column will explore novel ways of presenting social precariousness, practices of cultural expression and forms of ethics that emerge in the midst of political crises. It will do so through the lens of Han, Kazakh and Uyghur migrant responses to urban development in the city of Ürümchi in Northwest China.

Come back next Thursday for the first column in this series, about the “Uyghur Justin Bieber.” The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia will run every other week from then on.