Whether or not you’ve ever been to Beijing, you can now get a thoroughly enjoyable 90 minutes of nostalgia via King of Peking, a light-hearted indie film that’s just been added to Netflix.

King of Peking is a cinematic homage to the gritty, bootstrapped Beijing of the 1990s, when ’80s popcorn flicks were filtering their way into the culture (Lethal Weapon is a recurring reference) and the era of ubiquitous bootleg DVDs was just dawning. It’s the second feature by Australian director and long-time Beijing resident Sam Voutas, following his 2010 debut Red Light Revolution, which earned him a fanbase both in China and the West.

The film captures a transitional Beijing that is now all but gone, a “Wild West” period that came after economic opening up but before the forced renovations and forced relocations that have swept the city in recent years. As such, it hits the target better than most works of nostalgia for the recent past — but then again, Beijing moves faster than most cities.

Even without a background in all that, King of Peking is a clever and compelling story, and serves as a great introduction to such wonderful elements of modern Chinese life as the popcorn cannon. Fittingly enough, it’s already being bootlegged — though you can rent it for 99 cents via iTunes or stream it on your Netflix subscription.

Voutas is already deep into his next project — a graphic novel about foreigners in Beijing called Ride East, Face West — but he took the time to answer a few questions about King of Peking as it moves from touring the festival circuit to widespread digital distribution.

Zhao Jun behind the scenes (photo by Angus Gibson)

RADII: Your debut Chinese-language feature Red Light Revolution was a bootstrapped, labor of love deal, and ended up receiving positive reviews both within and outside of China. How did you get the idea for King of Peking, and what were the biggest obstacles you had to overcome to make it?

Sam Voutas: I was on Sanlitun bar street in 2012 and saw pirated copies of Red Light Revolution for sale. I had to laugh because the pirates had done a lot of work trying to promote the movie, creating their own movie credits on the back of the box, designing their own artwork and the like, and I thought, “Wow, these guys really believe they can make money on my movie, maybe there is hope!”

Just the idea of a few passionate people working out of basements trying to create their own bootleg film studio, there was something appealing in that. And then when it came to obstacles, the biggest was simply the fact that we were making a film set in the heyday of DVDs. And Beijing doesn’t look the same any more. So just finding locations, and creating the art design for those days, that was the most difficult part.

I know you got the project off the ground with a Kickstarter campaign. Where was most of your support coming from?

Because Red Light Revolution was released in both China and the West, we had an audience that wasn’t just based in one place. There might be someone who liked the film in Amsterdam, and another person based in Anhui. And myself and the producers, we wanted them both to be able to support our crowdfunding campaign for the next film.

Our problem was that the Western crowdfunding platforms didn’t work very well in China. They were either periodically blocked, or no one in China had heard of them, meaning they had no brand recognition, or they only accepted Western credit cards. So in the end we decided to do two separate campaigns, one right after the other. One was in English on Kickstarter, which generated about two-thirds of the crowdfunding revenue, and the other was on Zhongchou in China.

What has your distribution plan for the film been? How did you get picked up by Netflix?

From pre-production, the producers and I knew we were aiming for digital distribution on this movie. On Red Light Revolution, even though we did do theatrical distribution in a few countries, our audience in the end was mostly online, via our China release deal with [streaming site] Tudou. So that really laid the groundwork for how we approached this film.

For independent film nowadays, the internet is really where you’re going to find your audience. So getting the film released by Netflix, or a similar platform, has been in the DNA of this project from the get-go. We viewed our film festival run as our theatrical run — if people wanted to see the movie in the cinema, there were festival screenings to go to. So we never really chased a theatrical release on this. The holy grail for us was a large internet release.

This is your second time working with Jun Zhao as your leading man. How was your rapport this time around?

I love working with Zhao Jun. He was such fun on Red Light Revolution, and he’s grown even more as an actor since then. We have a similar sense of humor, and we just communicate really well together on set. We have a bit of a short-hand when we’re filming together which makes everything so much easier. When writing the screenplay for this one, I always had him in mind for the part. So it really was a natural fit.

The plot of King of Peking involves a father-son team who bootleg DVDs. This plot plays on a classic trope of Beijing street life, but at the same time feels like a swan song: the infamous gray market DVD stalls that were a defining feature of the city’s fabric are being picked off as areas like Sanlitun’s bar street get sanitized and flipped to higher-end real estate. Was there a feeling of nostalgia or a commentary on how Beijing is changing today at play when you were putting together the script?

It’s funny you mention the swan song! I really felt like the Beijing I’d lived in for so many years was slipping away. That the town wasn’t the same one I’d fallen in love with. I’m a bit of a strange case in that I was living in Beijing in the ’80s for a period, and the ’90s for a period, and again in the 2000s, so each time I’d come back to Beijing there’d always be this sense of loss, that the town was no longer the same.

But it feels the change is bigger now. And the one thing about getting older — I’m in my late thirties now — is I started to get really sentimental for parts of Beijing that weren’t around any more. So I really wanted to make a cinematic homage to those memories, even if they were just about lovable characters running bootleg stalls.

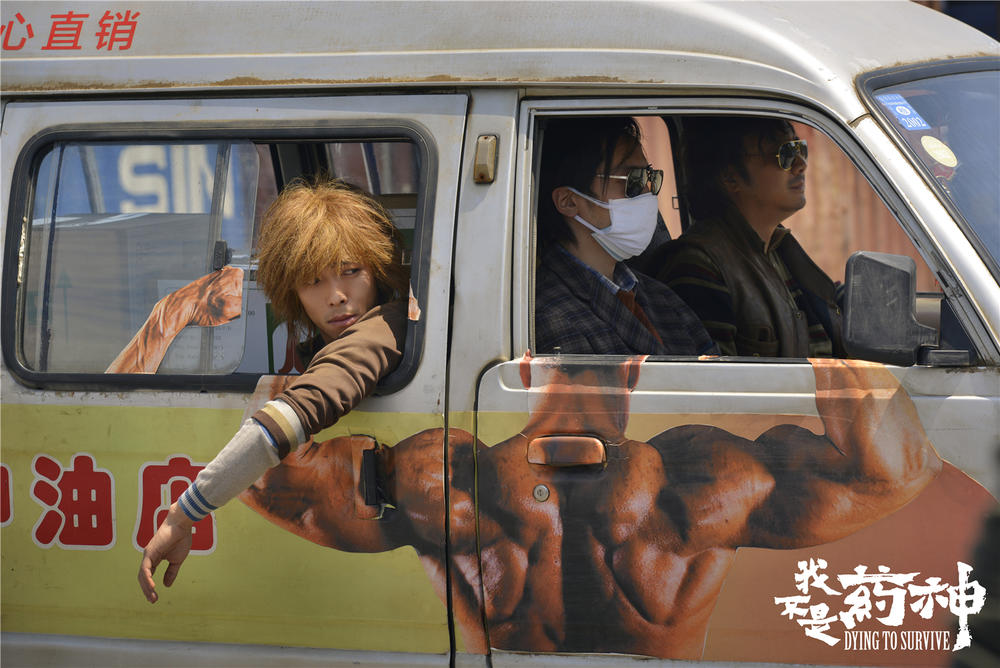

Zhao Jun in King of Peking (photo by Angus Gibson)

The plot of Red Light Revolution also revolves around an enterprising grinder setting up a semi-illegal storefront. Speaking to your own experience as an indie filmmaker, what opportunities does Beijing offer to people hustling on the margins, like hutong sex shop entrepreneur Shunzi in Red Light or Big Wong in King of Peking?

Back in the day, I think China was a really great place for entrepreneurs. It was like the early days of Silicon Valley, but for anything and everything. You could run a tiny street business selling yams, a few years later you could have a chain of them. You could start your own delivery company and all you needed was an electric scooter and an ice box on the back. The fact that there were entrepreneurs on any street corner, that was something that made Beijing and so many of these Chinese cities so special. You could be from out of town and with a dream, and there was a place for you to give it a go.

[pull_quote id=”1″]

And that’s one of the things that really saddens me about the closing down of so many small stores and stalls in Beijing, it has become so much more difficult for the entrepreneur. The heroes of my films are much harder to find on the streets these days. So in a way I’m making a Western here with King of Peking. It’s about the end of the Wild West, when the era is over and all you have is the stories.

—

Watch King of Peking on Netflix

All images by Angus Gibson, courtesy Sam Voutas

You might also like:

Photo of the Day: The Bricking of Jianchang HutongArticle Aug 13, 2017

Photo of the Day: The Bricking of Jianchang HutongArticle Aug 13, 2017

Photo of the day: A ’60s Beijing Bodega in BaitasiArticle Oct 13, 2017

Photo of the day: A ’60s Beijing Bodega in BaitasiArticle Oct 13, 2017

Here are China’s Big Summer Blockbusters for 2018Article Jun 30, 2018

Here are China’s Big Summer Blockbusters for 2018Article Jun 30, 2018