In life, he was devoted to the Party; his death nearly toppled the CCP from power.

It was 9:00 in the morning on April 8, 1989, and Hu Yaobang had a meeting to attend. Hu had been a key figure in China’s reform and opening since the ascension of Deng Xiaoping to power in 1978. Although he had been relieved of his position as General Secretary of the CCP two years earlier, Hu was still a member of the Politburo and an important voice. This happened a lot in the 1980s and 1990s. Every once in a while, David Lee Roth would show up to band practice, and the rest of Van Halen would look at each other and whisper, “He does know we fired his ass, right?”

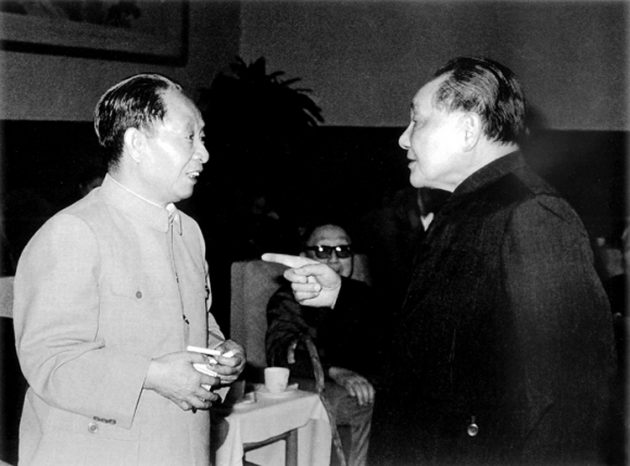

As the meeting began, Hu Yaobang suddenly pitched forward and turned pale. The meeting continued, but about 45 minutes later, Hu excused himself, rose to his feet, and then collapsed against a table. He turned to Zhao Ziyang, a fellow architect of reform and opening, an occasional political rival, and — as current General Secretary — played Sammy Hagar to Hu’s Diamond Dave. “Comrade Ziyang…”

A week later, on April 15th, Hu Yaobang died. The nation had lost one of its most beloved leaders. Students in particular looked to Hu as a leader with liberal sympathies, open to reform and fresh ideas (Hu once, possibly joking, suggested China abolish chopsticks in the interest of better public hygiene).

And at under five feet tall, Hu was perhaps the only member of the government who the diminutive Deng Xiaoping could post up at the annual Zhongnanhai 3×3 hoops tournament.

Hu had also been instrumental in rehabilitating victims of Mao-era purges. His sympathies came from experience. Along with Deng, Hu had been removed from power more times than the Venezuelan electrical grid. It was Hu Yaobang, reportedly, who worked to bring Xi Zhongxun, father of current Chinese leader Xi Jinping, in from the cold after the elder Xi had been cast into political purgatory during the Cultural Revolution.

In China, there is a long tradition of mourning the dead to rebuke the living, a bit like how US Democrats today can’t stop praising Joe Biden. The day after Hu’s death, people gathered in Tiananmen Square in a spontaneous demonstration of grief. The politburo was also receiving reports of student-organized memorial activities on university campuses.

When the party leaders met to discuss plans for Hu Yaobang’s memorial service, Premier Li Peng warned: “We should keep a close eye on the universities, especially ones like Peking University.”

Education Minister Li Tieying replied: “Things are good at the universities. It’s not very likely there’ll be any trouble.”

As reassurances go, this has to be up there with the casino manager who figured the book was safe with Tiger at 14-1 so “go ahead and take that chump’s money.”

Hu’s death gave students an opportunity to express their grief as well as an outlet for their frustration at the lack of political reform and the rise of corruption and their uncertainty about their futures as an educated elite in a changing economy.

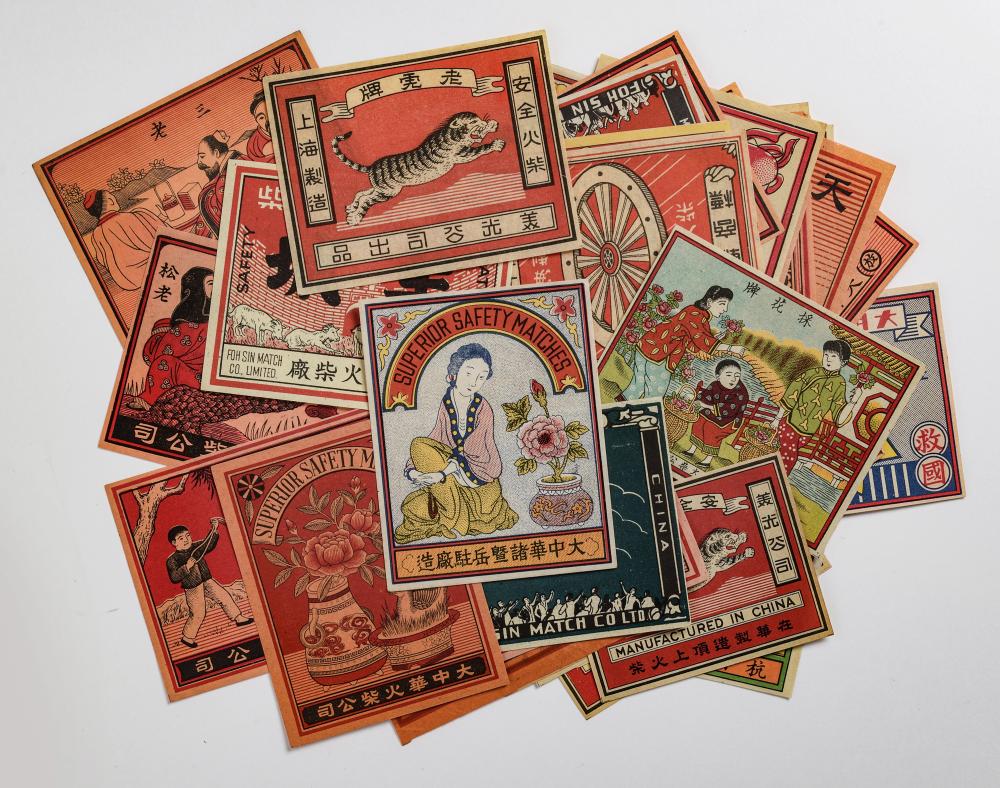

It was also about being tired of having to respect strange little men in matching black uniforms and retro eyewear.

Sorry! I posted the wrong photo from our “1980s Relics” folder. Here we go…

The students placed wreaths and banners around the Monument to the People’s Heroes, gave speeches, and demanded that they be given a greater role in the official memorial service.

Hu’s funeral, held in the Great Hall of the People, took place on April 22. That same day, over 50,000 students converged on Tiananmen Square. They carried signs and shouted slogans, and demanded to be let inside. They had come to petition the government and had a letter addressed to Premier Li Peng.

Over the next six weeks, the numbers of demonstrators grew as ordinary citizens joined the students to express their own grievances. Despite increasingly stern warnings and threats from party leaders, the square filled with people, each with their anxieties, dreams, complaints, and hopes and united by the possibility of change.

Many outside of China still refer to the 1989 protests as a “democracy movement,” but Hu Yaobang was a democrat (little “d”) in the same sense that Julian Assange’s cat could be considered an “ideal house guest.” More than the other guy, sure, but you have to remember what that other guy is capable of. Hu represented a vision of China’s future where economic development could occur within a framework of greater openness.

Whatever the possibilities of that model, June 4th made such a direction politically unpalatable for China’s leaders. But for a moment, on April 15, 1989, on a spring day in Beijing, Hu Yaobang came to symbolize in death the aspirations of a generation.