Here is something for the cartography nerds out there: If you take a map of China and draw a straight line from Heilongjiang province in the Northeast (on the border with Russia) across to northern Myanmar, you will have cut the country essentially in half geographically.

Now, most of what we think of as China is to the east of this line: my house in Shanghai, soup dumplings, bustling megacities from Beijing to Shenzhen, that delicious lamb noodle shop in Deqing I go to sometimes — all of it. East of this line lives over 1.2 billion people. This is the Hu Line, or the Hu Huanyong Line (胡焕庸线).

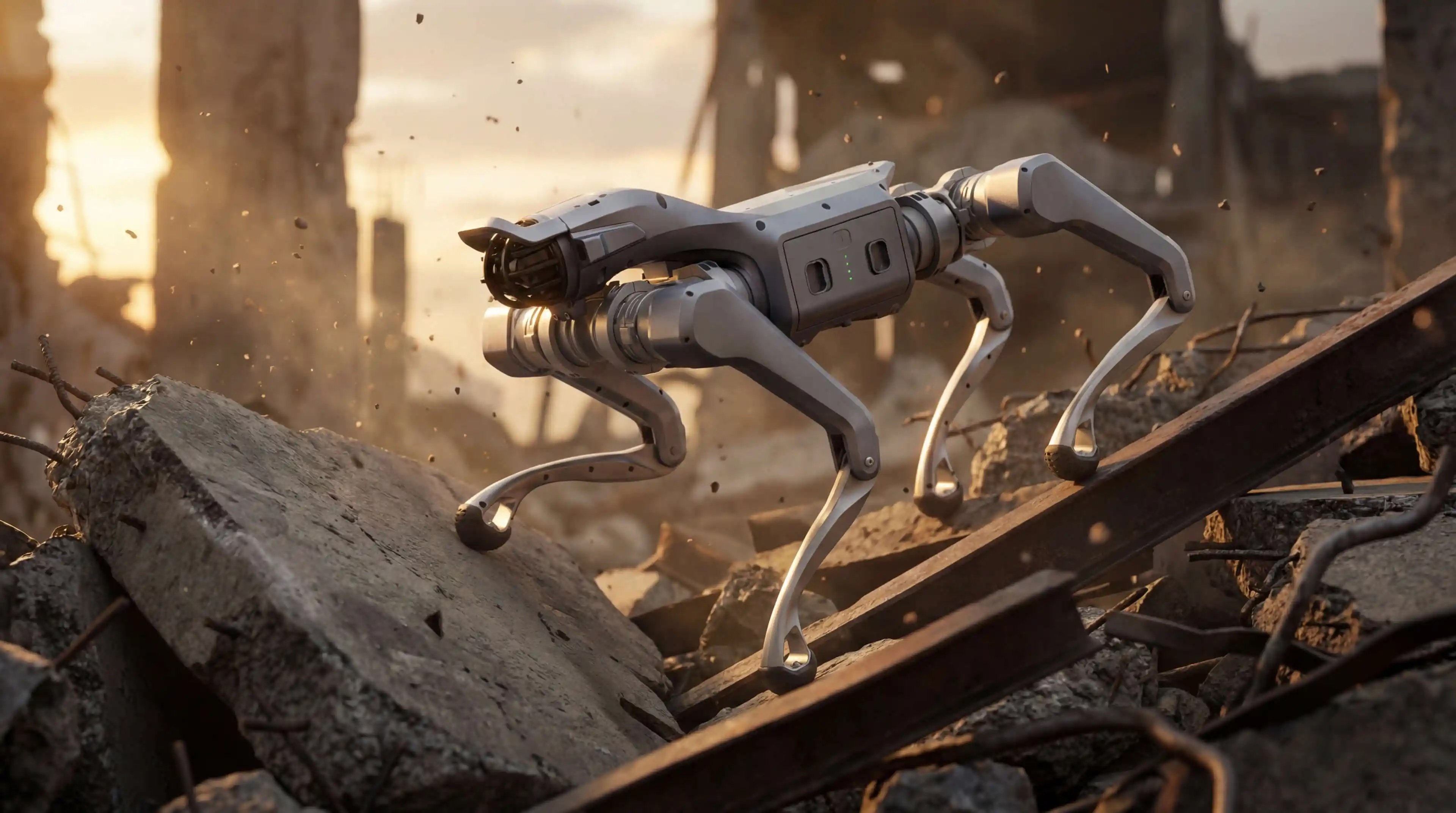

West China’s Gansu province

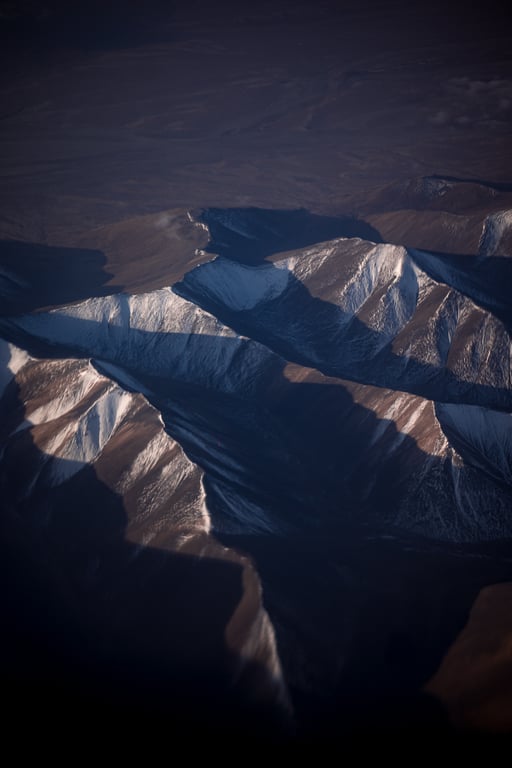

To the west of this line is an entirely different story, both demographically and economically: much of the land is barren, desert, and high plateau, home to less than 5% of the population and a diverse spread of ethnicities.

Camels on a lonely patch of earth in Gansu province

The provinces and autonomous regions of Xinjiang, Qinghai, Tibet, Inner Mongolia, and Gansu make up most of this area. Each is enormous, sprawling, and sparsely populated.

Gansu

Last year, I had the chance to explore the Aksay Kazakh Autonomous County in Gansu, sandwiched between the border of Xinjiang and Qinghai — a high plateau plain area.

Gansu

You tend to see more Tibetan antelopes and camels than humans in a place like this. Despite the subtle marks of civilization — a tag on a camel, a powerline heading off in the distance — for the most part, it was hours of driving alone in wide, rocky valleys under a blue sky.

Camels in Ningxia, a small autonomous region in China’s vast and sparsely populated West

The region is about the size of Switzerland but is home to only 10,000 people. It was one of the first times since living in China that I felt genuinely alone — no planes overhead, no farms, nor the hum of a distant tractor.

Turning off the only main road, all you have is a satellite map to guide you.

Gansu

I think it’s important to remember that this is what literally half of China looks like: vast, rolling, rocky land, with mountain ranges in the distance and the crunch of sand beneath your boots. From Everest to the Gobi desert to the rolling grasslands of Inner Mongolia.

Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region

Of course, the region is incredibly picturesque. You have the Himalayas in Tibet and beautiful coniferous forests in Xinjiang that could easily be mistaken for Canada.

What captivates me most, though, isn’t these postcard-quality sights, but the otherwise mundane expanses that stood between China and the rising and falling civilizations in the West for thousands of years.

Gansu

Above is a photo of the Hexi Corridor, an incredibly important bottleneck of the Silk Road, where all of the silk, porcelain, and tea that the West craved was carried just before leaving China.

Ningxia

Today the historical territory is part of the patchwork that makes up China, providing economic value not only from the commodities crossing these lands but also from tourism, energy production, a handful of growing cities, and countless film sets dotted throughout the nation’s Northwest.

Ningxia

These are far from empty landscapes: Some of China’s most incredible historic sites and tastiest cuisines call these rolling expanses home — not to mention a fascinating abundance of wildlife and various communities and cultures that trace their roots back thousands of years on the ancient lands.

You might also like:

PHOTOS: Global Award-Winning Wines Come from This Chinese RegionChinese wine isn’t well-known internationally, but China’s winemakers are working hard to change thatArticle Nov 08, 2021

PHOTOS: Global Award-Winning Wines Come from This Chinese RegionChinese wine isn’t well-known internationally, but China’s winemakers are working hard to change thatArticle Nov 08, 2021

All images courtesy of Graeme Kennedy