Despite living in Beijing, I rarely feel immersed when it comes to language practice. English speakers can visit just about any corner of the earth and find their native language on customs forms, street signs, menus, t-shirts and subway platforms. Even here, in the “faraway Orient” (Mussolini’s words, not mine), it’s all too easy to forgo deciphering logograms when the English translation is never far away.

So, I went looking for the best deep-dive into the Chinese language that wouldn’t be boring or expensive.

What I found was zhibo – live streaming – and calling this the deep end doesn’t do it justice.

In the Western world of Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, etc., live streaming exists as a subset of already extant social media platforms; useful for news organizations and performers to broadcast an event or themselves to their most dedicated fans. But in China, zhibo is an industry in and of itself, and a fast-growing one at that. In the past year, this wacky thing that barely existed a few years ago took in over $4 billion in revenue and is on track to triple by 2020.

It’s not just celebrities, either; zhibo apps are in the business of creating stars, not just giving existing ones a platform. All over China, people are building serious audiences with serious incomes to match. Of the 710 million Internet users here, at least half of them have tried a live streaming app. That’s nearly the population of the United States.

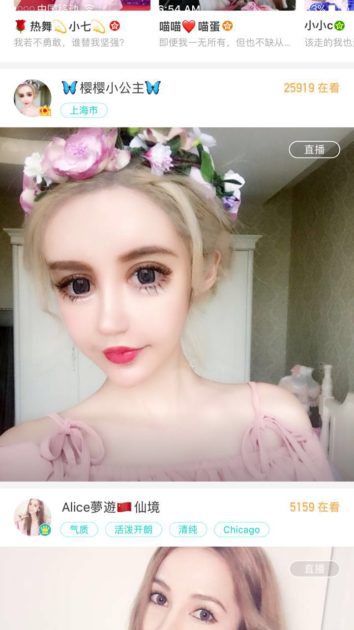

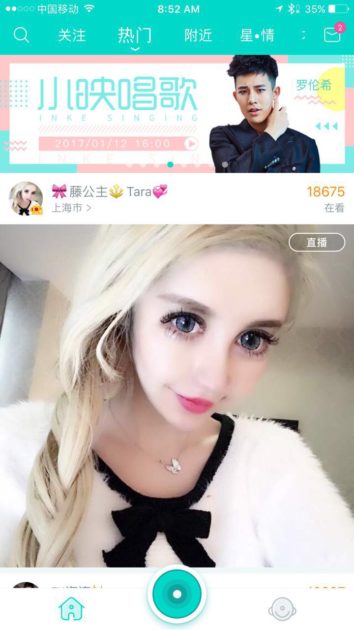

So it was on the advice of a friend that I downloaded the streaming app Yingke — English name: Inke Live, or YK for short — and started scoping things out…

The first thing I noticed was the heavily edited profile pictures – girl after girl with vampire-like skin and eyes ranging from somewhat subtly enlarged to full-on funhouse-mirror-freakshow. The gap between profile picture and reality can be pretty striking and occasionally hilarious, but let’s assume that most of our Western readers are familiar with Tinder pictures and move on.

Click on any one of the Barbie/Ken-like pictures on the front page (literally called hot door) and you enter that user’s streaming room. And now we reach the crucial question that most readers probably have: What do these people do? This whole world was so unfamiliar to me that I’ve gained a new appreciation for what our grandparents must have experienced as we attempted to explain the value of Facebook and Twitter.

Users are, in essence, sorted according to the celebrity holy trifecta: being funny, being good-looking, and being talented. This is further broken down by categories such as witty, talented, hunky, babes, melodious, humorous, etc. While watching a stream, you can tag a user based on their attributes, and that becomes part of the algorithm that decides who makes it to the front page. The result is that you have a few types of streamers: performers who sing and play instruments, specialty channels for calligraphy and working out, and most significantly, pretty girls being pretty for the benefit of millions of lonely young guys (even in China, the Internet is the Internet). In fact, there are so many pretty live-streaming girls and so many lonely guys that the government had to crack down on eating bananas on camera – literally. Too many girls were, um, let’s call it “nibbling” on bananas to get around the “no eroticism” rules.

And to answer the natural question of why people would spend their time streaming themselves doing next-to-nothing for millions of people, look no further than the streaming rooms of the biggest stars. They are bombarded with a nonstop flood of “gifts,” or flashy digital stickers worth anything from a tiny fraction of an RMB to a “Ferrari” sticker worth over 100 yuan.

Watch one of the most popular rooms for an hour, and you’ll watch them make a few thousand RMB – and that’s just on Yingke, one of the smaller-money apps. This is the sort of micropayment strategy that “freemium” gaming companies like Zynga has mastered. For individual users, spending a token amount on some stickers is probably a good dopamine-for-money tradeoff. For those receiving batches of those token amounts, it can add up to a pretty decent salary.

So with the vague notion that this service could be a huge moneymaker – and a general desire to have complicated Internet slang thrown at my face – I sat down on my couch one evening, turned on some lamps, and hit “start streaming.” I then immediately turned it off because 27 people were in the audience, “likes” were coming in, and I didn’t have a clue what to do. The first thing I realized was that I couldn’t be doing this sober. So, drink in hand, I gave it another go.

As for what the actual hell to say, I found a pretty easy solution: as the likes came in, I would simply say hi to the person hitting like. Endlessly repeating, “Hello, [name],” might sound boring, but in Chinese, names are often made up of obscure characters used exclusively for names, so it provides a decent challenge. On top of that — this being the Internet — a huge percentage of names are jokes, puns, references, etc., and my failed attempts to read them – and occasional successes – are of great interest (read: hilarity) to viewers. Through the sheer virtue of being able (or not able) to say names, I managed to earn myself my first handful of subscribers.

From there, things developed pretty quickly. Unsurprisingly (and unfairly), I have a pretty serious advantage on Chinese live streaming; there are many, many millions of users on Yingke, but only a tiny fraction are foreigners. I’ve only seen four or five on the front page in the half-year I’ve used it (though confusingly, people on the app will still tell me how surprised they are to see “so many foreigners”).

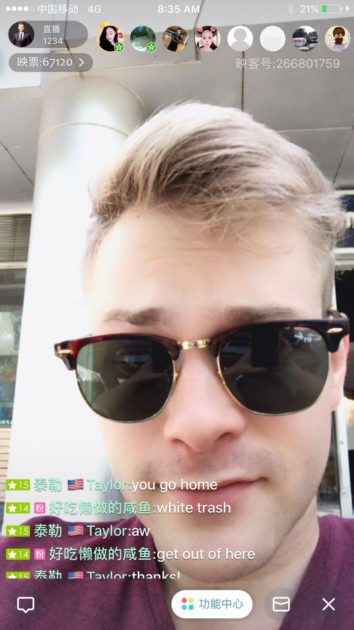

Yep, looks like a pretty diverse user base to me!

Between making friends with people who are genuinely interested in learning more about foreigners (a heartening percentage), cracking jokes with those who express good-natured surprise at my existence (also a good amount), and making everyone else laugh by engaging the trolls yelling racist nonsense (tame by the standards of any YouTube comments section), I’ve found it surprisingly easy to pass an hour chatting with viewers in Chinese. At time of writing, I’m closing in on 3,000 subscribers, with an all-time audience high of 22,000 people. That’s tiny by normal standards, but it’s provided me with a half-decent foothold in this strange new world. Come back next week to watch the weirdness unfold!

Spoiler: trolls may be involved