Though they’ve spent the last few years focusing on the intersection between agriculture and technology, Xiaowei R Wang‘s resume of working with tech in China is long and varied. Many of the projects they’ve been involved with are process-oriented and community-based, such FLOAT, an interactive design project that sent Arduino-linked air-quality-sensing kites up in public parks around China, and LOOP, a user-generated community radio that popped up in Beijing for the 2015 JUE Festival.

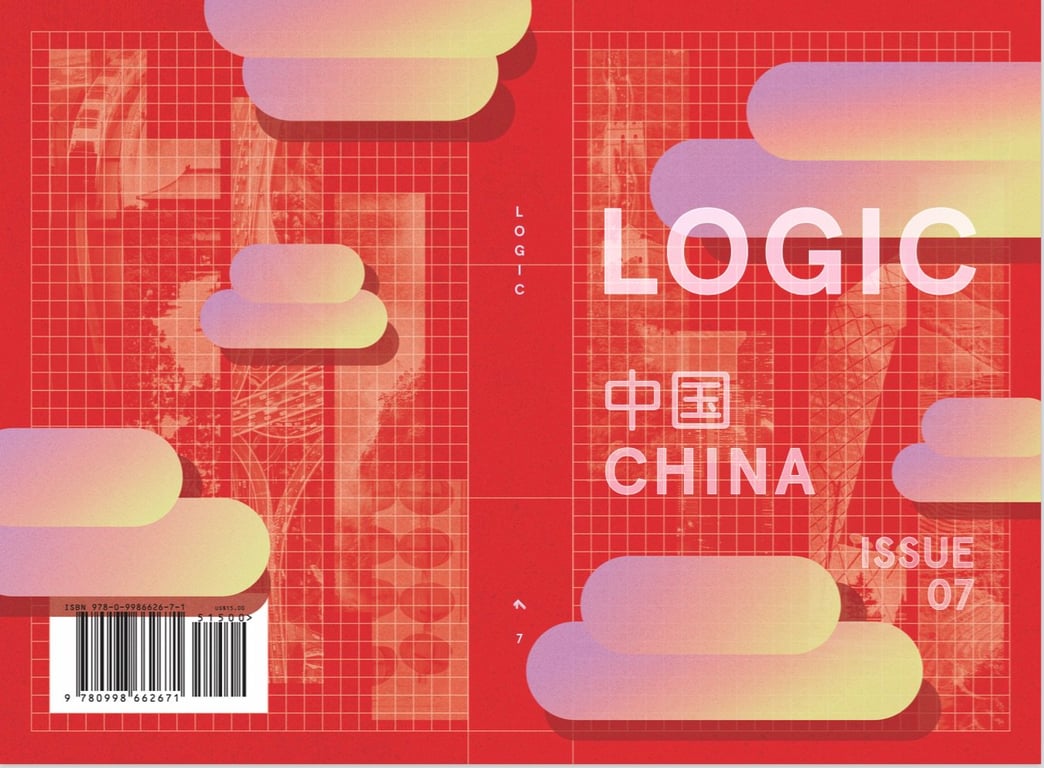

The latest one-word project Xiaowei’s become involved with is Logic, a technology magazine initiated in 2016. Xiaowei was drafted from the project’s beginning as Creative Director, and has just put together a full issue on China for the magazine’s 7th issue, out now. Logic‘s China issue tackles trending topics (censorship, surveillance, social credit) and less covered facets of technology in China (rural-urban divide in internet use, changing government attitudes towards online freedom) in equal measure, commissioned and shaped by Wang to “present a rounder, more nuanced picture of the tech landscape in China today.”

I sat down with Xiaowei to discuss the driving logic behind this issue of Logic, and where they hope it falls along “China watcher”/”tech watcher” divide:

Xiaowei R Wang at Alibaba Cloud Headquarters, Cloud Town, Hangzhou

RADII: One of Logic‘s defining features is the wide thematic scope of each issue, with themes like “Play”, “Sex”, “Justice”. In different ways each theme is both specifically evocative yet vague enough to avoid easy definition and encourage broad dialogue. How did you select “China” and how do you think this word, ostensibly a place name, functions in a similar way as a theme like “Sex” or “Intelligence”?

Xiaowei R Wang: Themes like “Play” or “Justice” are all words that have different meanings, depending on who in tech you ask — these words have become mythologized into everyday tech vocabulary. In that sense, China as a place is no different, especially through the eyes of the West. There’s the China that exists everyday, on the ground, and then there’s “China” manufactured by media to propel the American government towards certain economic decisions. There’s also the China of Silicon Valley’s dreams — a place to get rich, corner part of the China market. In this sense, by theming it China, we wanted to make explicit China as a place and as a projection of technological desires and anxieties.

By theming it China, we wanted to make explicit China as a place and as a projection of technological desires and anxieties

photo by Xiaowei R Wang

In an introductory text on Logic‘s website, you frame this issue by questioning the Western stereotype of Chinese technology and industry as imitator, not innovator — a reversal of theme that has become more common in the last several years as publications such as Wired marvel at novel technological leapfrogs such as mobile pay and social credit. Going a bit earlier in time, it could be argued that so-called “Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics” has been producing innovative adaptations in industry and tech since the Reform era began at the end of the ’70s. But you go further to argue that technological innovation and “dreams of rapid modernization” have been baked into China since the founding of the PRC in 1949. Can you elaborate on this? What do you think are some interesting innovations or localized technological solutions that define Mao’s China?

We think of technology as software and chips now, but technology more broadly and the disruptions it causes are not new. I think of Carlota Perez’s great work, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital. Similar anxieties to the ones we have today — of AI taking our jobs (technological unemployment), etc — have all existed in the past. With the ascent of the CCP and establishment of the PRC, though, I think there is a “technological solution-ism” baked into the PRC. What I mean by this is a position of economic and political governance based on finding solutions, extreme pragmatism, and the combination of ideology mixed with science and technology (like any typical Marxist ideology, where science and tech are intrinsically ideological).

For the US, I would say that legacy is a bit different, you can read the origins of science as tied into religion and cosmology. You can contrast this in the writings between Boris Hessen on the development of science and technology from a socialist, Soviet view to Alexander Koyre’s writings on Newton with a much more European lens.

And certainly much of these attitudes, the pragmatism tied into China’s one party system, but there is definitely a pragmatism that underlies the Chinese approach to economic and technological development.

AI mushroom growing tent (photo by Xiaowei R Wang)

I think that is present in history — there’s a good book, Mr. Science and Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution, that talks about science during the Mao years. It covers a lot of the early ties between politics and science (which makes some scholars say “real” science never existed in early China, because the idea is that science brings democracy because you have to have people debating stuff and doing experiments, right?). The book also has some of the experiments and technologies used in the early PRC, like a group of researchers at Zhongshan University in the 1950s looking at sulfur metabolizing bacteria, so that sulfur could be removed from low-grade iron ore. There was also a “mass science” movement where peasants and workers were encouraged to set up laboratories and communes for things like crop experiments.

We think of science as non-political, but the way it’s formed into a national program or agenda is very much influenced by ideology and politics

That to me is the really interesting departure in early PRC from Western science — the avoidance of reliance on Western ideas of what science is, and the derision towards “elite science,” instead emphasizing mass science for the people. Of course, this is so explicitly political, but it gives us a way to understand Western science and technology better too. It makes total sense that in the West, we were focused on the individual genius, the Enlightenment Era man, and that led to Big Science in the 1940s. Basically, we think of science as non-political, but the way it’s formed into a national program or agenda is very much influenced by ideology and politics.

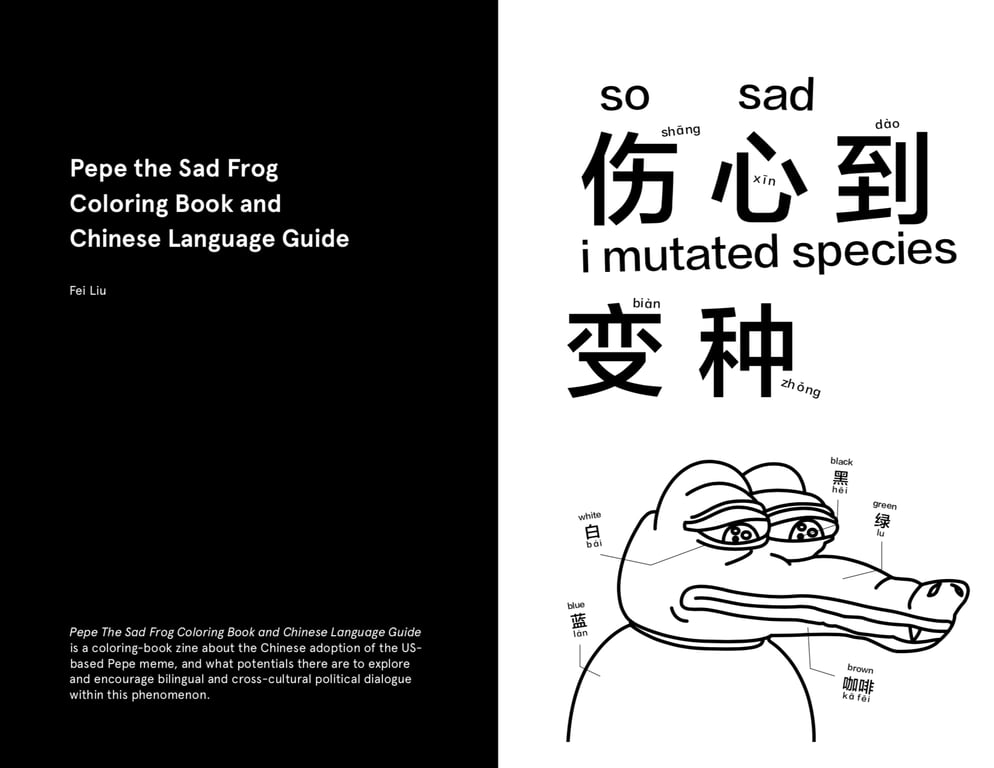

“Pepe the Sad Frog Coloring Book and Chinese Language Guide” by Fei Liu in Logic #7

One article in the new issue of Logic is “a genealogy of the Chinese Communist Party’s relationship to technology.” How has the PRC’s use of technology changed under different eras of CCP leadership?

One of the biggest changes is the government’s attitudes towards the internet and internet freedom. Before Xi, there was the Great Firewall, but you could still get around it. Now, there are not only more and more crackdowns (like the government using deep packet sniffing to detect VPNs), but the government is using social media and the Internet for explicit propaganda purposes, like the Little Red App (xuexiqiangguo). In the Logic China issue, Lü Pin talks about it, where there was the Xi eating buns incident. The incident was staged precisely for a social media environment, and that really signaled how the new powers-that-be were not only going to examine everything on the internet, but they were going to control and manipulate information in a way that prior leaders hadn’t done. There’s that whole trope of Jiang Zemin being a meme right now but let’s face it — it wasn’t intentional. Nor could you imagine Jiang Zemin or Hu Jintao deliberately staging things for social media. They weren’t that savvy.

In the process of choosing submissions to include and organizing them under different sub-headings, what key questions about China were you trying to answer, or what cliches/stereotypes were you trying to dispel?

The biggest cliche was trying to dispel China as a scary, monolithic force. We tried highlighting the rural-urban divide in internet use, showing the trajectory of how online speech became restricted under different leaders, and the origins of things like surveillance in Xinjiang.

One thing I’m aware of is how siloed “China coverage” is. Like, you can be a “China person” or a “tech person,” but if you’re a “China tech person,” that always gets lumped into China category first and foremost. But that’s so odd to me, given the globally connected forces of finance, hardware and software in the tech industry. By showing the history, the context, and the origins of certain conditions in China, I think we’re bringing it to new audiences, and also going beyond the existing tech coverage of China, which is often just business reporting.

Related:

![]() China Exports Facial Scan Tech to Zimbabwe, Launches First “AI Technology Entry to Africa”Article Apr 16, 2018

China Exports Facial Scan Tech to Zimbabwe, Launches First “AI Technology Entry to Africa”Article Apr 16, 2018

An entire section of the magazine is grouped under the sub-head “Command and Control.” Western media have no shortage of stories about how the CCP is using technology like facial recognition, biometric databases, AI-enhanced surveillance, and social credit to “command and control” China’s population. What do mainstream media accounts tend to get right, and what do they get wrong? How do the articles in this issue of Logic provide more nuance to these conversations?

So, I’m going to have to pull in Said’s Orientalism here. I think with the surveillance stuff, it’s very much a techno-orientalism that happens. We point to China as a surveiled, sinister place, primitive and despotic. But then after that critique, we don’t do much. It’s basically a patronizing approach, because we still cast the US as somehow a place where things are much better, where there isn’t surveillance happening. As we know, that’s not true.

There’s a lot of nuance to surveillance in China. For the issue, we have Shazeda Ahmed writing about social credit. She’s one of the few experts who’s devoted years of study to the topic, both in policy docs as well as interviews and ethnographies. There’s a lot of good writing at the China Law Blog about social credit as well. It’s not as simple as a universal citizen number by the government. With biometric databases and AI-enhanced surveillance, it’s also not monolithic. China’s a big country and so much policy is regionalized. The situation in one province does not automatically extend to the other. What we’re doing with the articles in that section is trying to show the finer threads, nuanced reports of social credit and surveillance in specific parts of China, and how it’s not the same across the entirety of China.

We’re trying to show the finer threads, nuanced reports of social credit and surveillance in specific parts of China, and how it’s not the same across the entirety of China

Other pieces in the magazine cover apolitical cultural tics that have grown in the unique context of the Chinese internet, like bullet commentary and certain “meme mutations.” What are the most surprising, alien, engaging or provocative behaviors that have arisen in the “walled garden” of the Chinese online ecosystem, and are unlike internet behavior/culture anywhere else in the world?

What’s really fascinating in that section on Chinese social media, is the overlap between economics/politics and social expression online. I won’t spoil it, but Christina Xu‘s piece shows the overlap between fan culture, bullet comments and “the mob,” and Hatty Liu talks about how e-commerce becomes an area where class politics are played out.

I think livestreaming, especially Kuaishou, is the ultimate alien, surprising, bizarre and beautiful online behavior I’ve seen so far. There’s just so much happening on it.

Related:

“The Internet Giveth, the Internet Taketh Away”: Director Hao Wu on “People’s Republic of Desire”Article May 08, 2018

“The Internet Giveth, the Internet Taketh Away”: Director Hao Wu on “People’s Republic of Desire”Article May 08, 2018

You finish the issue with a section including sci-fi/speculative fiction authors Chen Qiufan, Hao Jingfang and Ken Liu. How do you think science fiction influences science in China, if at all? Has the success of Liu Cixin, Haoa and Chen made a meaningful impact on how Chinese society envisions its present and future?

Well, Hao Jingfang is definitely incredible because her day job is to research and help build policy towards China’s future economic development. And I think she has an organization that works with impoverished children and education. Anyway, I think the success of Chinese sci-fi within China and globally has definitely impacted the way society sees itself. There was that Sixth Tone article Chen Qiufan wrote about the release of the Wandering Earth, and how that’s significant as a way to bring Chinese culture to the world stage.

In this sense, it introduces the element of soft power through culture, right? And that’s really exciting to see! For so long the West was the originator of music, art and literature, which really shaped cultural values across the world. And now there’s a sense that the US isn’t the only one who’s exporting soft power via culture.

“I Believe in the Individual”: Hugo Winner Hao Jingfang on Creativity in ChinaArticle Jun 13, 2017

“I Believe in the Individual”: Hugo Winner Hao Jingfang on Creativity in ChinaArticle Jun 13, 2017

What do you hope a Western reader takes away from this issue? In a time when people in the West are apprehensive about the use of technology both in their own backyards (Palantir, Facebook) and in China (Huawei, Google Dragonfly), and in a time when latent fears about “China’s rise” are front and center in Western political discourse, what do you hope to impart about China and technology that isn’t being communicated in the prevailing media narrative?

We hope that Western readers understand that China is not a monolith. In fact, I would say because Logic only ships within the US right now, the issue is mainly targeted towards Western readers.

For so long the West was the originator of music, art and literature, which really shaped cultural values across the world. And now there’s a sense that the US isn’t the only one who’s exporting soft power via culture.

Anything you want to add?

There is a lot of great reporting on tech in China in English, both TechNode and especially Abacus (run by South China Morning Post). It’s funny, even though we talk about the internet connecting everyone, I feel like the outlets we read are still very siloed! I hope more Western audiences read Abacus in the future.

—

Pick up your digital or print issue of Logic #7 here.