Across Chinese social media, millennials are bellowing a widespread battlecry.

The target? Marriage, and the prospect of having kids.

It began with a post from state media outlet People’s Daily on the microblogging site Weibo in June, listing artifacts of ‘90s-era nostalgia. The post lamented that the generation born after 2020 (hereafter referred to as the “post-‘20s” generation) will come to view those born after 1990 the way post-‘90s once viewed their elders.

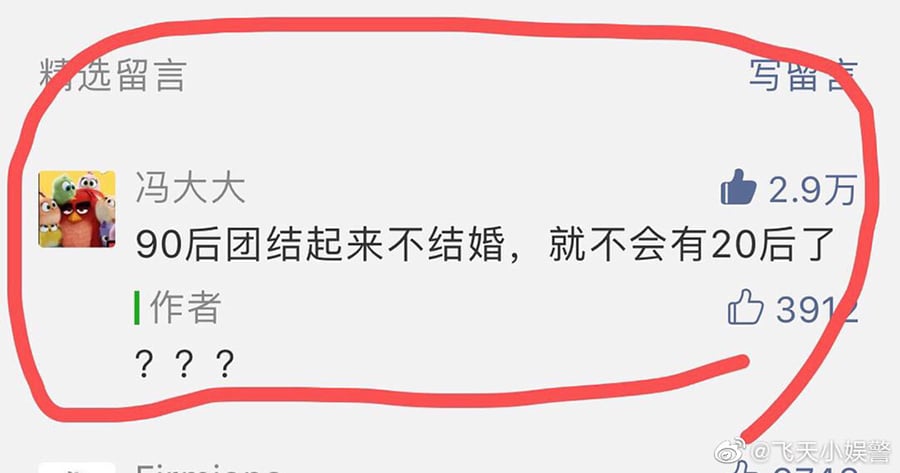

The comparison hit a nerve, so much so that one defiant commenter declared, “If post-‘90s unite to not marry, the post-‘20s will not exist,” essentially threatening that if ’90s kids make a pact not to reproduce, there wouldn’t be any future generations.

The comment that would soon become a viral hashtag

The comment became a viral hashtag (“#只要90后足够团结,就不会有20后了#”) that quickly amassed 150 million views and over 20,000 posts on Weibo.

What exactly has caused post-‘90s millennials to rally around this fatalistic battlecry? A multitude of factors are causing a generation in their reproductive golden years to feel resistant to the perceived “restraints” of marriage and procreation.

Til Debt Do Us Part

Since China’s One Child Policy ended, the nation’s birthrate has continued to plummet in recent years, causing no small amount of panic over the economic repercussions of population aging and a shrinking labor pool. The government has made it clear that procreation is a matter of national interest and even patriotism — and while we see younger generations are far from averse to patriotic behavior, the call to settle down and make more babies for their country is falling on deaf ears.

The most obvious deterrent for having children is the thankless economics of the act. Cost of child rearing in China is at an all-time high, and no new government subsidy program has rolled out alongside the updated fertility policies. With rising commodities prices and real estate costs still sky-high, raising an infant is just another money drain.

30-year-old writer Echo Lau quips:

“There’s a popular saying among young people that ‘the most effective contraceptive is high real estate prices.’ I think if apartments become cheaper, more people will want to get married and have kids.”

Fu Yizhou, a 25-year-old man working in e-commerce, further laments, “A new addition to the family does not add a new set of income to offset all the new costs. The whole family must make concessions.”

For the post-’90s generation — which saw a huge spike in standards of living in their formative years — it’s not only a personal setback, but also irresponsible parenting. As the wealth gap continues to widen, the competition for success begins at birth with the best infant milk formula for brain development, and continues with English classes for toddlers and extracurricular activities. Those who can afford to shell out for premium experiences can give their children the edge they need. And now that many ’90s kids have reached adulthood, with parents who gave them the best, the thought of not being able to do the same for their offspring is a heavy psychological burden.

The Parent Trap

Is it all about the money? Would cheaper apartments stimulate a baby boom? Not exactly.

The appeal of a lighter economic burden is contingent upon the willingness to get married, and that offers plenty of misgivings for China’s post-‘90s generation. Fu blames it on the commitment phobia rampant within his generation, saying, “We’ve had a lot of things easy as the sole focus of our parents, so we are repelled by responsibility.” This is in line with Wu Zhihong’s famous book The Nation of Giant Babies, which discusses the narcissism and risk-aversion displayed by the One Child Generation.

Related:

Film of Shanghai Marriage Market by “Leftover Woman” Goes ViralArticle Mar 19, 2018

Film of Shanghai Marriage Market by “Leftover Woman” Goes ViralArticle Mar 19, 2018

“To me marriage is trouble,” says July Wang, a 26-year-old woman who works at Douyin. “It creates problems for me in terms of economics and freedom.”

A popular meme on Weibo teases people for falling into the so-called “trap” of marriage. “Why get married?” the meme reads. “Is your milk tea no longer delicious? Are your video games no longer fun? Are your TV shows no longer engaging?” For a group of people said to lack capacity and drive to make major decisions that demand compromise and sacrifice, the seemingly endless pool of diversions is a much more alluring way to spend their time and money. Comparatively, marriage and children represent nothing but compromise and sacrifice.

Some of the “Why get married?” memes

Forever Young

And that’s to say nothing of the gendered issues surrounding marriage and children. Post-‘90s women and men each have their own reasons to be resentful of the institution.

For Dan Wu, a 25-year-old man who works in IT, marriage is steady, but stale. “Marriage offers a lot of stability, but it also means losing the sense of adventure of the hormone-stimulating courtship period,” he explains.

Related:

Wǒ Men Podcast: Under Red Skies – Inside the Minds of Chinese MillennialsAuthor and former New York Times journalist Karoline Kan joins the Wo Men Podcast at the Yenching Global Symposium to discuss how history has helped shape China’s millennial generationArticle Apr 02, 2019

Wǒ Men Podcast: Under Red Skies – Inside the Minds of Chinese MillennialsAuthor and former New York Times journalist Karoline Kan joins the Wo Men Podcast at the Yenching Global Symposium to discuss how history has helped shape China’s millennial generationArticle Apr 02, 2019

Fu meanwhile believes that post-‘90s men are inclined to reject marriage and children because “they are very immature.

They see themselves as boys and they want to keep having fun,” he explains. “They also don’t have the biological distress that women must deal with.”

This would explain why many married women complain that their husband is just like another child for them to take care of, rather than someone to share responsibilities with.

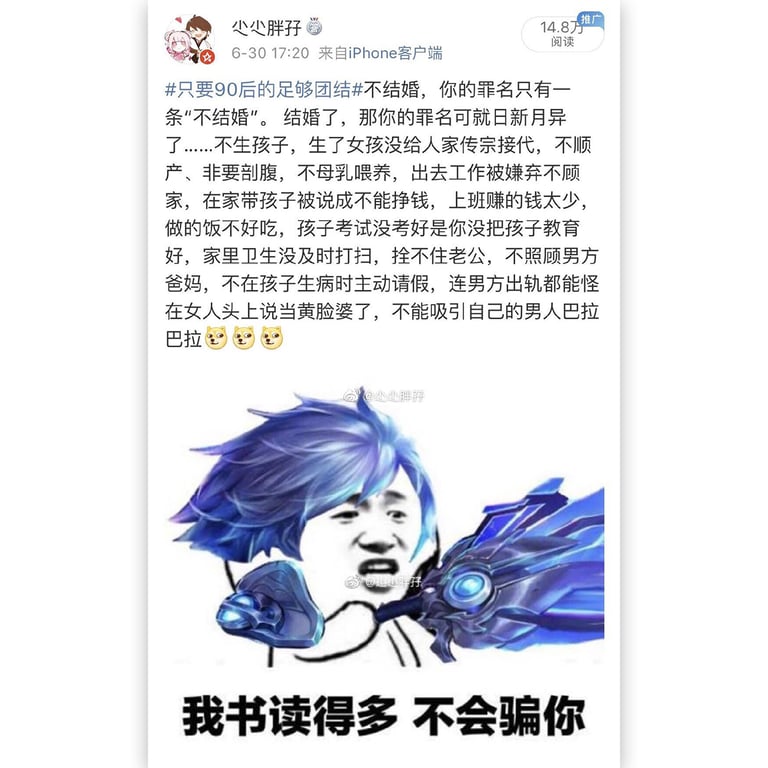

A widely shared Weibo post bearing the “#If post-’90s unite#” hashtag explains the situation from a woman’s point of view — a long, wretched laundry list of inescapable “failures” a woman will be blamed for if she does not excel at every aspect of her life (even those beyond her control).

The viral “laundry list” on Weibo, ranging from “not earning enough money” to “child doing poorly on an exam because you didn’t educate them properly” to “not doing housework in a timely fashion”

The list effectively illustrates the harrowing reality of modern womanhood in China. For well-educated, white collar women in big cities, rather than resigning themselves to suffering, many of them eschew unattainable standards of the perfect wife and mother to nurture their careers, their hobbies, and enjoy their freedom.

Related:

Lipstick Messages, Bunny Massages, and Marathon Manicures: Sexist Stereotypes Hit Chinese HeadlinesArticle Nov 05, 2018

Lipstick Messages, Bunny Massages, and Marathon Manicures: Sexist Stereotypes Hit Chinese HeadlinesArticle Nov 05, 2018

But are so many women really determined to remain unmarried for life? For Lai, this all depends on whether she can find a partner who will support her through this ordeal.

“In the future, things will be better, but for now, getting married and having babies means dealing with nagging in-laws and values from a very different time,” she says. “I will only go through this if I find a partner that I truly love, so that I would not be alone to face the music, and so that he would not be an additional burden for me to bear.”

Header image: Mayura Jain