The 15th edition of the George Town Festival is set to return from July 19th to 28th, bringing a vibrant celebration of arts and culture this summer. Whilst this is the Malaysian coastal city’s most anticipated annual festival honoring its unique heritage and global artistic talents, the festival has recently gained attention for perhaps not the most ideal reasons.

Its organizers released a promotional video that sparked criticism from the Malay community, who felt it did not properly represent and feature their cultural heritage, instead focusing exclusively on festival programs related to Chinese and Indian culture. In the end, the organizers decided to remove the videos and issued an apology.

Nonetheless, Penang’s colorful annual event will still enthrall audiences, promising over 80 programs from around the world and exploring new perspectives.

Here are 10 programs to look forward to at this year’s festival!

Performing Arts

Yam Seng Lah!

Created by the Dabble Dabble Jer Collective in collaboration with Michelin-selected Curios-City restaurant in Penang, this is a unique theater and dining experience that promises a sensorial journey where a curated menu is paired with personal narratives reflecting Malaysian culinary heritage and culture.

Date & Time: July 20 & 21, July 27 & 28 2024 | 11:30am & 6:30pm

Duration: Approx. 150 minutes

Venue: Curios-City

Language: English

Double Bill of Jingju Magic

A theatrical experience that merges traditional Chinese opera with modern theater, this program features two compelling excerpts — “Avenging Zidu” and “Zhuangzi Tests His Wife” — which delve into the complexities of human nature, showcasing the extraordinary physical prowess and artistry of the Jingju (aka Peking Opera) performers. Dubbed the “Eastern Macbeth,” the actors masterfully evoke the audience’s imagination with stylised action, bringing landscapes and characters to life on the minimalist stage.

Date & Time: July 19 & 21

Duration: 90 minutes

Venue: Dewan Budaya USM

Language: Mandarin, with English and Mandarin subtitles

Visual Arts

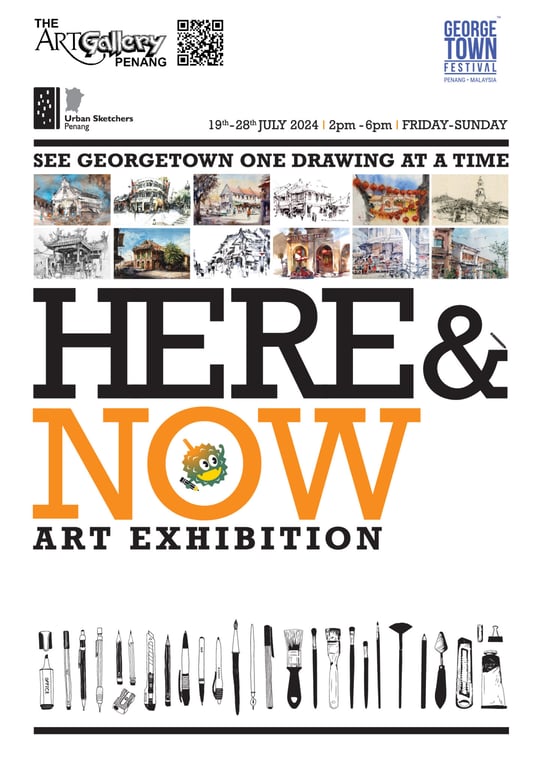

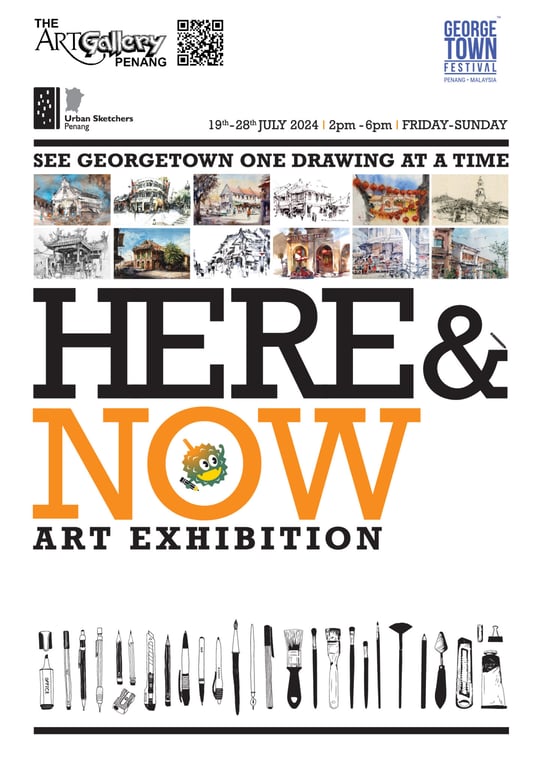

Here & Now Art Exhibition

“Here & Now” is an electrifying showcase of sketches by the creative collective Urban Sketchers (USk) Penang, who have been dedicated to the art of on-location drawing since 2010. Through the unique interpretations of 12 artists, the exhibition invites viewers to experience Penang’s vibrant streets and tranquil waterfronts like never before, with USk Penang transforming the city’s treasures into art one delicate brush stroke at a time.

Date & Time: July 19-21, July 26-28 | 2:00pm-6:00pm

Venue: The Art Gallery, Penang

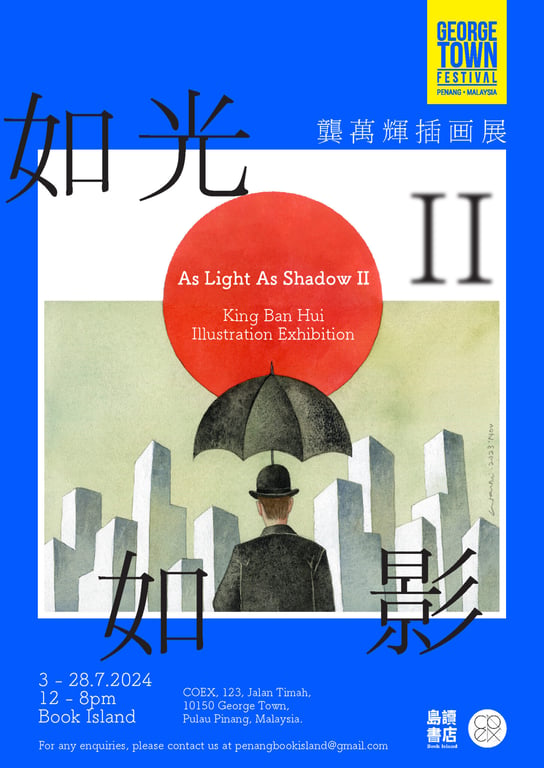

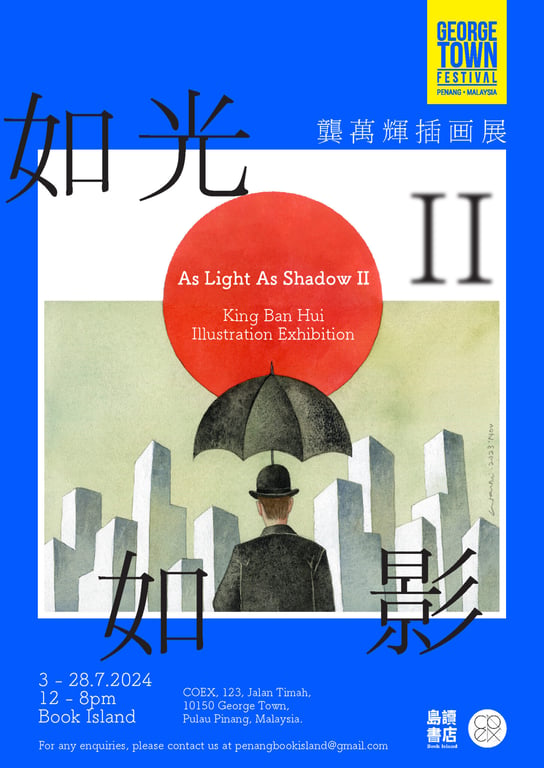

As Light as Shadow II: King Ban Hui Illustration Exhibition

Teeming with imagination and surreal narratives, this exhibition showcases evocative hand-drawn illustrations by Malaysian-Chinese artist and writer, King Ban Hui. His works are often featured in newspapers, magazines, and book covers in Taiwan and Malaysia.

Date & Time: Now until July 28, 12:00-8:00pm

Venue: COEX @ Kilang Besi

Artists-in-Residence

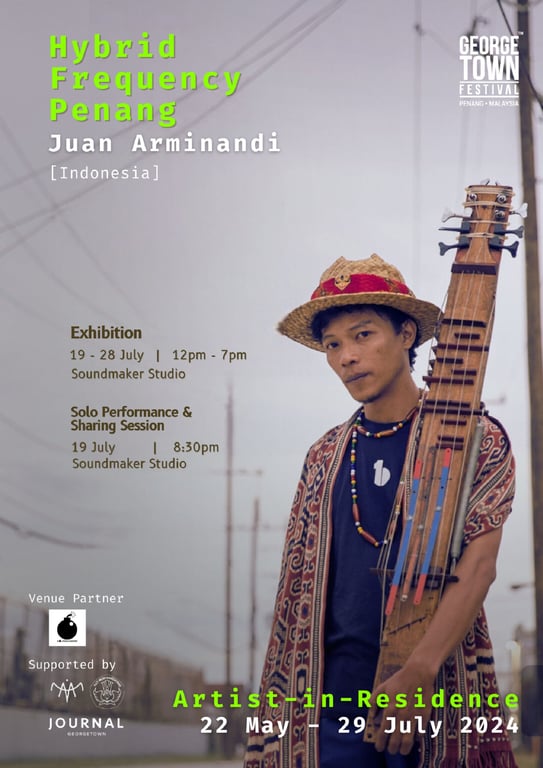

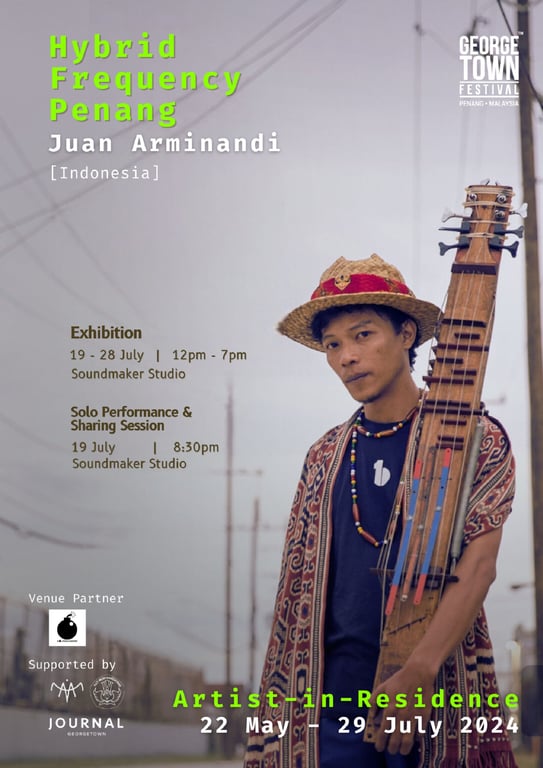

Hybrid Frequency Penang

Hybrid Frequency Penang is an experimental project in which Indonesian artist, Juan Arminandi, becomes a human recorder — capturing sights, sounds, smells, and feelings of George Town through dynamic interactions with the local community. Arminandi’s observations are then transformed into musical instruments in collaboration with local communities and then performed in a musical performance.

Date & Time: Exhibition: now until 28 July, 12:00pm-7:00pm, solo performance: 19 July, 8:30pm

Venue: Soundmaker Studio

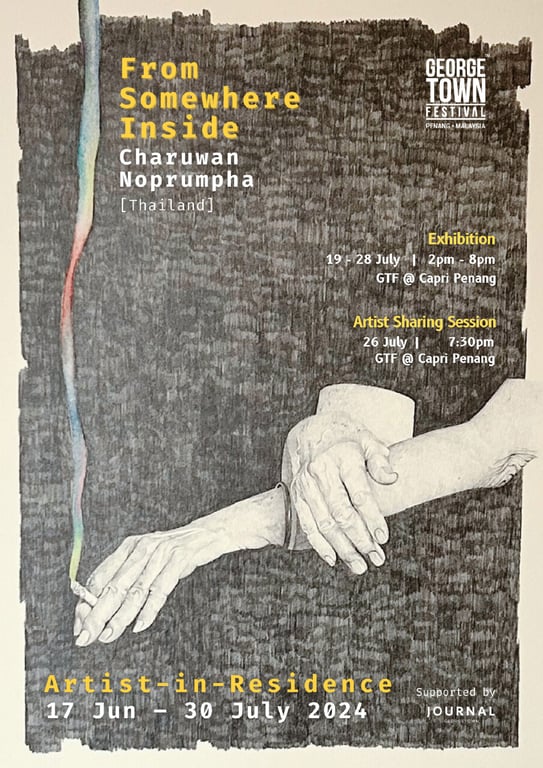

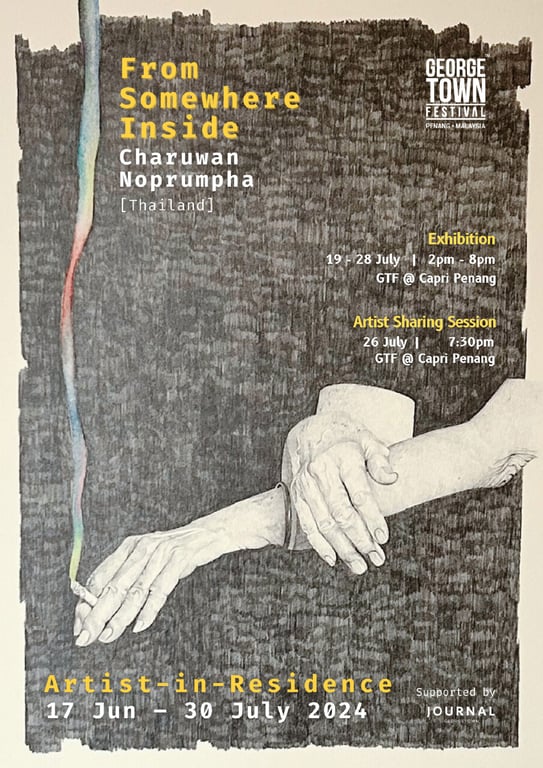

From Somewhere Inside

A participatory project by Thai visual artist Charuwan Noprumpha, who observed and collected items from local communities in George Town, then translated traces of their everyday lives into abstract artworks that capture moments and allow viewers to observe through an outsider’s perspective. Her works have previously been exhibited in countries such as Belgium, France, Germany and Thailand.

Date & Time: Exhibition: Now until 28 July, 12:00pm-8:00pm, Artist Sharing Session: 26 July, 7:30pm

Venue: GTF @ Capri Penang

Workshops

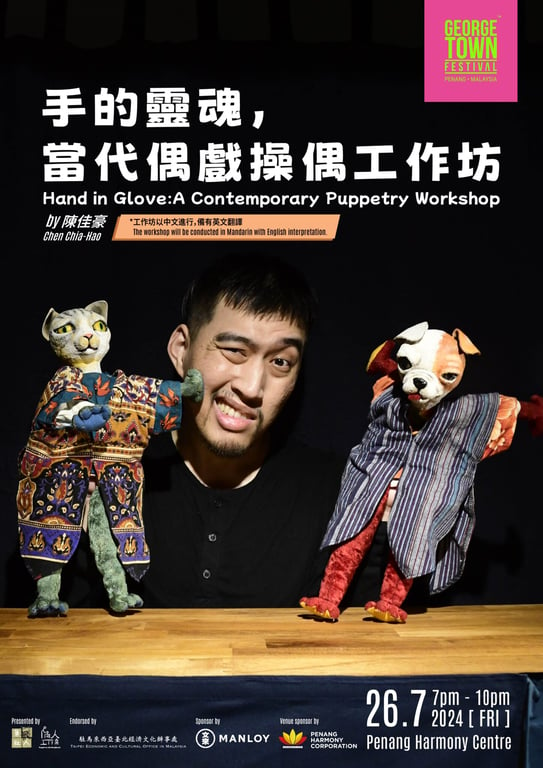

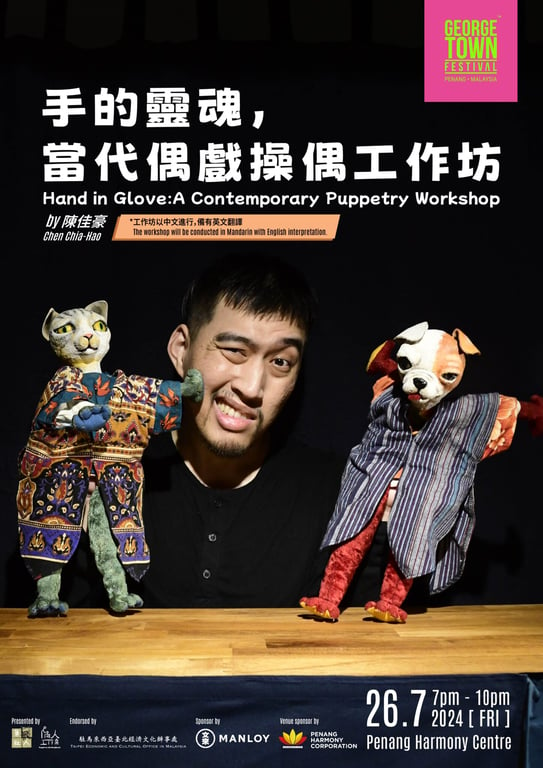

Hand in Glove a Contemporary Puppetry Workshop

In this contemporary puppetry workshop led by Taiwanese puppeteer Chen Chia-Hao, participants will explore the joy and boundless possibilities of the art form, using traditional glove puppetry hand training as a foundation to discover their own “hand creatures” through imaginative exercises.

Discussions will also delve into the choice of puppets and their implications, while exploring changing positions and the relationship between puppeteers and their puppets.

Date & Time: 26 July, 7:00pm – 10:00pm

Duration: 3 hours

Venue: Penang Harmony Center

Language: Mandarin, with English interpretation

Real-Time Unconventional Instrument Workshop

Led by Bulgarian musician and sound artist Mirian Kolev, this workshop explores how any sound can be turned into music through the use of unconventional instruments and methods — such as field recordings and small sound devices. Participants will learn to create real-time compositions and explore the expressiveness of music, with the workshop recommended for those interested in music composition and sound editing.

Date & Time: July 21, 10:00am – 11:30am

Duration: 1.5 hours

Venue: The Courtyard @ Beach Street

Language: English

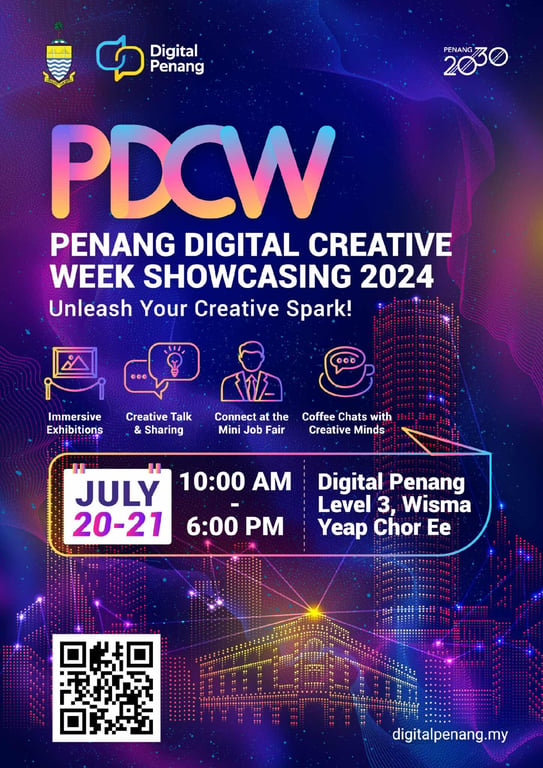

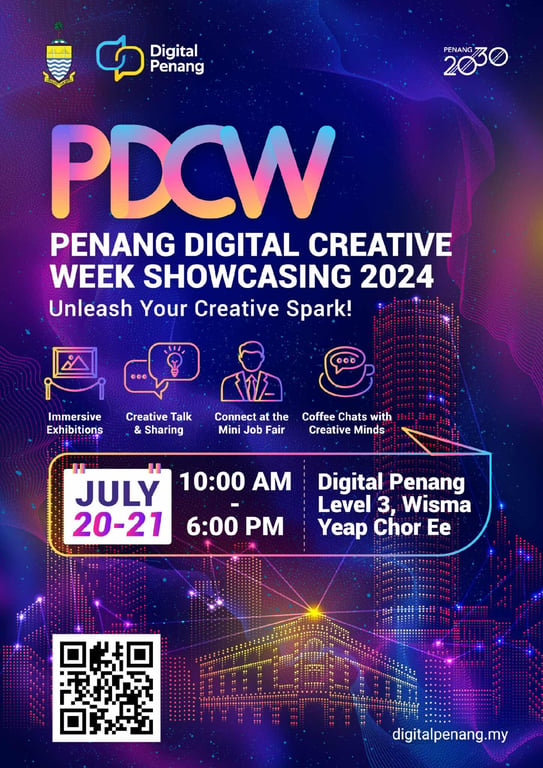

Penang Digital Creative Week Showcasing

A digital transformation initiative by the state government’s agency Digital Penang, Penang Digital Creative Week (PDCW) aims to nurture young creative talents and companies. The showcase features exhibitions, sharing sessions, a mini job fair, and chats with creative minds, where selected projects receive development funding and mentorship. Through PDCW, Digital Penang aspires to firmly establish Penang as a hub for creative talent and companies.

Date & Time: 20-21 July 2024 10:00am-6:00pm

Venue: Digital Penang Level 3

Negaraku

Showcasing a curated selection of works from the prestigious collection of Malaysian collectors Bingley Sim and Ima Norbinsha, this exhibition is a heartfelt tribute to Malaysia and features pieces to celebrate the country’s vibrant culture, captivating history, and breathtaking natural beauty.

Date & Time: Now until August 11 | 12:00pm-7:00pm (weekdays), 11:00am-7:00pm (weekends)

Venue: Hin Bus Depot

For more information, visit George Town Festival’s website or check out the program itinerary here.

Banner image via George Town Festival.