Rock climbing has become a popular sport in recent years, and it took the world stage for the first time as an Olympic event at the delayed 2020 Tokyo Games. The Olympic rock climbing competition included three disciplines: speed climbing, bouldering, and lead climbing. But outdoor rock climbing offers a different sense of adventure from the climbing on artificial walls and plastic holds seen at the Olympics. While China has a healthy presence at international climbing competitions, if you’re in the country and want to try climbing outdoors, where should you head? For many rock climbers, the answer is Yangshuo, a small county close to the city of Guilin.

Hiking to Bamboo Cave Crag. Photo via Team Sustainable Yangshuo.

Thanks to its karst mountain landscapes (even featured on the 20 RMB bill!), Yangshuo has developed into an outdoor climbing destination over the past three decades. In 1990, American climber Todd Skinner established the first sport climbing route in China, Proud Sky (5.12b on the Yosemite Decimal System, a widely used climbing grading system), at Moon Hill in Yangshuo, marking the beginning of modern climbing in the country.

Eight years later, Huang Chao, the Chinese owner of a Western restaurant on Yangshuo’s busiest commercial street, was exposed to climbing culture through his international customers. Huang Chao would go on to develop many more crags in and around Yangshuo, leading an increasing number of locals to start rock climbing.

After decades of growth, Yangshuo now has over 70 crags and 1100 climbing routes. A wide range of routes in different styles has attracted climbers of all levels from around the world. Climbers in Yangshuo can be broadly categorized into three groups: tourists, regulars, and professional climbers.

Tourists, naturally, are outdoor enthusiasts who visit Yangshuo to climb, ranging from beginners trying the sport for the first time to intermediate climbers who own some basic gear. Regulars are dedicated climbers who can climb grades above 5.10 (a benchmark for moderate difficulty). They visit Yangshuo periodically, own their ropes, and are adept at lead climbing (climbing a route without a rope already placed at the top) and placing protection. Professional climbers, meanwhile, reside year-round in Yangshuo, often working as climbing or outdoor guides. They possess advanced climbing skills, able to climb routes ranging from 5.12 to 5.14.

Climbing in Yangshuo. Photo via Team Sustainable Yangshuo.

The latter two groups are most active in the climbing community and are often referred to as yányǒu (岩友, climbing friends). Some yányǒu are Yangshuo locals; others moved there from out of town, bringing their life experiences with them and enriching the area with their love for art, culture, sports, and nature.

This growing community has gained the attention of the global climbing community. Last June, The North Face held its annual Mountain Festival in Yangshuo, providing guests the opportunity to explore the area through outdoor activities such as canoeing, camping, and, of course, climbing. Canadian outdoor brand Arc’teryx also led an edition of its Academy workshop series in Yangshuo last October, hosting talks on topics ranging from climbing techniques to opening new routes.

Yet these brands also seem to be treating Yangshuo like tourists themselves, merely landing for events and then leaving. After a burst of activity and attention, what’s left for Yangshuo?

When it comes to making a last impact on Yangshuo, it’s up to the yányǒu then. And yányǒu status isn’t limited by nationality: American Andrew Hedesh has lived in China and work as an outdoor guide for more than a decade. His guidebook, China: Yangshuo Rock, is essential reading for newcomers to the climbing area.

Now, thanks to community groups like Team Sustainable Yangshuo (永续阳朔小组), Yangshuo’s rock climbing culture is even spreading beyond the county. Last year, inspired by a performance of the extreme sport artist group The Flying Frenchies, Flupke (Xiaojuan 小卷), a Yangshuo local and owner of Demo Bistro, conceived the idea of suspending a rock band from a cliff.

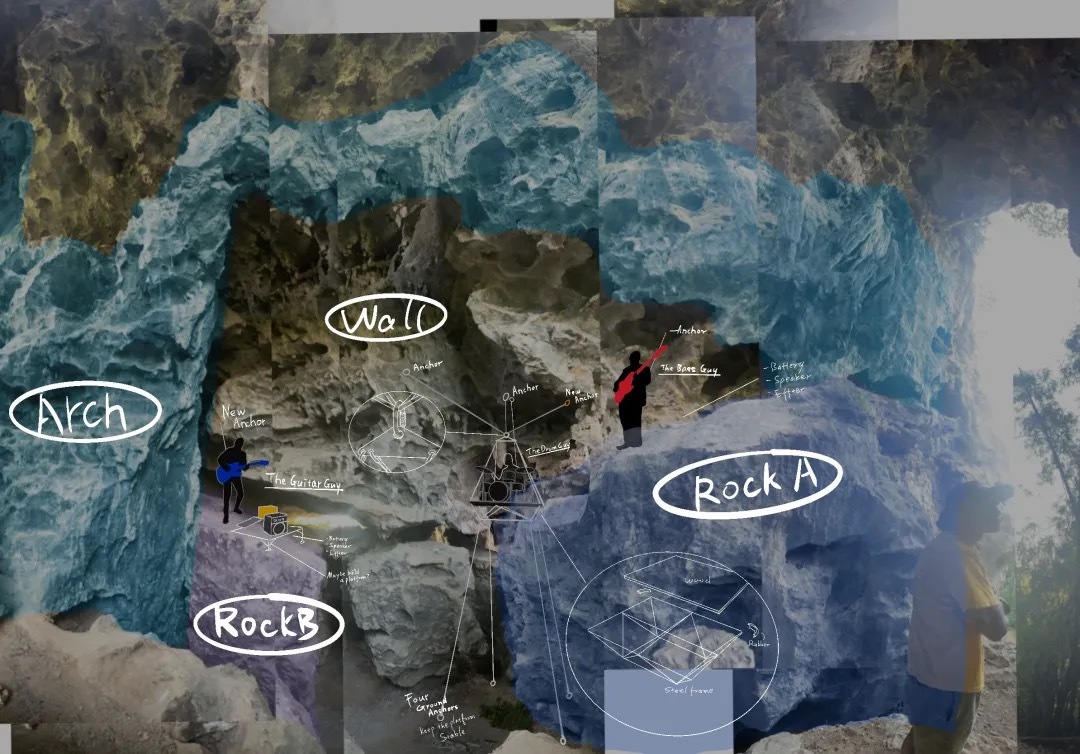

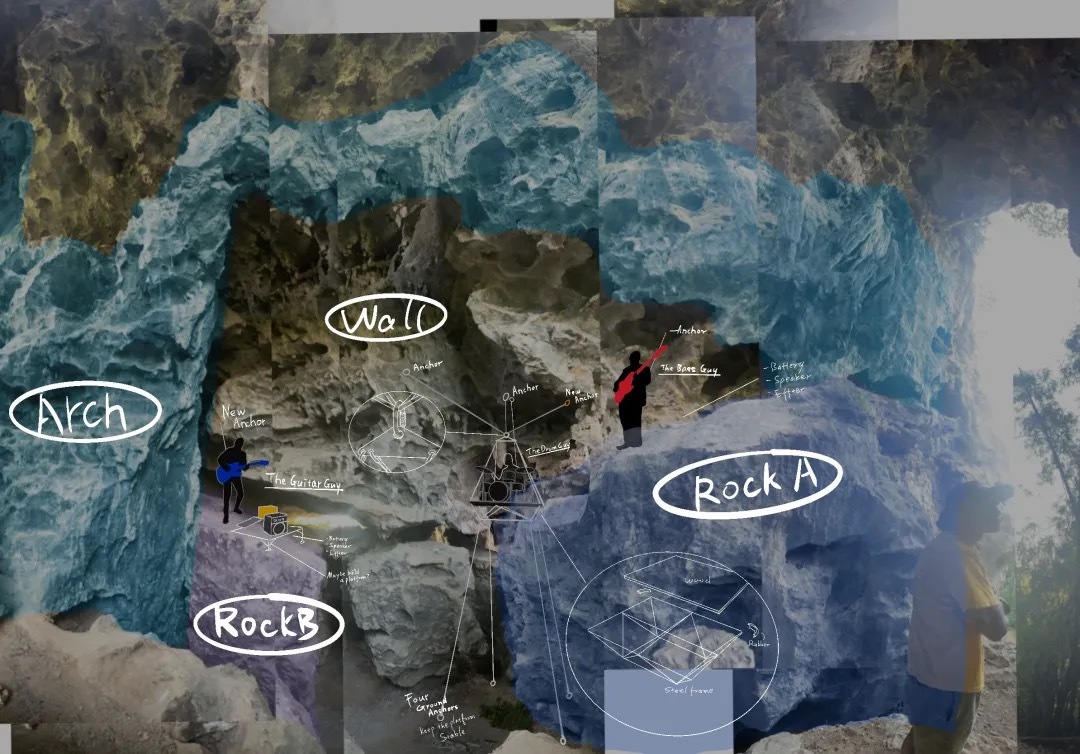

This was the beginning of Wildass Yangshuo (阳朔野崽). Julian Yang, an interactive installation artist and engineer, proposed a guiding principle: “Materials must be from Yangshuo and the fabrication process must take place there. All participants of the filming and executing team must be from the local Yangshuo community too.” This approach ensured that both the making-of the project and its final outcome fostered exchange between different social circles in the local community and made a positive contribution to Yangshuo’s economy. Gradually, more yányǒu embraced the concept, contributing their music, resources, and climbing expertise to Wildass Yangshuo.

Design sketch of the hanging band set up. Image via Julian Yang.

The hanging band performance took place last December in Yangshuo’s Bamboo Cave crag, drawing an audience ranging from other climbers to local administrative personnel. Team Sustainable Yangshuo later raised money amongst themselves to screen footage of the performance in New York’s Times Square, sharing Yangshuo’s climbing culture on an international platform.

Inspired by the success of the project, Team Sustainable Yangshuo plans to continue using rock climbing as a medium to enhance Yangshuo’s culture and ecology, through art residencies, educational projects, and sustainable commerce. Soon, they’ll be assisting a social activist with a spinal cord injury by developing a fully supported rock climbing program for people with disabilities, the first of its kind in China. The project aims to raise awareness about the living conditions and limited access to sports that people with disabilities face.

The hanging band performance. Photo via Wildass Yangshuo.

In the meantime, while Yangshuo is fortunate to welcome guests from around the world to share its abundant natural resources, maintaining a balance between local residents and visitors remains crucial.

Since its establishment in 2017, the grassroots organization Yangshuo Climbing Association (YSCA) has served as a bridge between the local government, villagers, and climbing enthusiasts. They have facilitated communication between villagers and climbers, for example mediating conflicts related to climbing routes next to ancestral tombs. Their efforts have brought benefits to both individual climbers and community groups like Team Sustainable Yangshuo.

However, several practical issues still need to be addressed, including transparency in qualification standards for climbing trainers and inadequate wages. As urban residents who may not have the opportunity to contribute in person except on holiday, what can we do for the sustainable development of this outdoor destination? According to Julian Yang, shifting away from a litterbug mindset — leaving behind garbage in nature and assuming professionals will remove it — and instead understanding Leave No Trace principles (LNT) would already be a significant step forward.

For further information on Team Sustainable Yangshuo, follow Wildass Yangshuo 阳朔野崽 on Xiaohongshu or @thisis_julianyang on Instagram.

Banner image by Haedi Yue.