That the zodiac this year lands on the Year of the Rat is something of a missed opportunity, because tigers are really having their year.

Besides the now meme-enshrined American miniseries Tiger King, 2020 has also seen the release of Chinese American writer C Pam Zhang’s acclaimed debut novel How Much of These Hills is Gold, set in gold-rush era California populated with mythical tigers. While it may not reach the big screen this year, surreal coming-of-age drama Tiger Girl from Andrew Thomas Huang is also in the works. And, despite the pandemic, 2020 brought Taiwanese-American screenwriter Alan Yang’s directorial debut Tigertail to Netflix too.

This last work in particular provides a rich opportunity for interrogating the recent growth of mainstream Asian American storytelling. Although Asian American cinema has been around for (almost) as long as Asian Americans have, much of it has been independent or even underground. The last few years, however, have witnessed a mainstream breakthrough.

Tigertail is one of a number of recent releases that ask us to ask ourselves: what are the tales that Asian Americans can tell and can “make” mainstream? How do these stories build upon or work from Asian cinema? And ultimately, how can we use these stories to build community?

Different Stripes

In an interview with The New York Times, the 36-year old Yang said that he was hopeful that Tigertail “could be some small source of comfort” to the Asian American community, speaking during a time in which there was an uptick in the number of hate crimes against Asians in the US. “It’s very much a love letter,” he stated. “Not just to my own family, but to every family that’s gone through this experience.”

Related:

Coronavirus Stirs Rumors and Racism Towards Chinese Eating Habits and HealthOn social media, ignorant rhetoric about food and health is spreading faster than the virus itselfArticle Feb 03, 2020

Coronavirus Stirs Rumors and Racism Towards Chinese Eating Habits and HealthOn social media, ignorant rhetoric about food and health is spreading faster than the virus itselfArticle Feb 03, 2020

Yang is perhaps best known as a co-creator of the Emmy Award-winning television series Master of None, alongside Indian-American actor and writer Aziz Ansari. Since the release of Tigertail in April, Yang, an alumni of NBC’s Diverse Staff Writer Initiative, has also been vocal in support of the Black Lives Matter movement, pushing the #8cantwait campaign, which asks for immediate change to police departments in the US.

Tigertail, his first feature film as director, explores the legacy of his family’s immigrant story, following Pin-Jui, a poor, young Taiwanese man who dreams of moving to America. During the day, Pin-Jui works with his single mother in a sugar factory, while at night he frequents dance halls and croons Otis Redding from memory. Pin-Jui loves a girl named Yuan, but when his boss offers to fund Pin-Jui’s immigration in exchange for marrying his daughter, Zhenzhen, he takes the deal.

In the United States, hard work and a loveless marriage erode his vibrant personality until he even has difficulty connecting with his own daughter.

The narrative is based on Yang’s father’s own immigration story, and it draws from real-life details. “Tigertail” is the English translation of Huwei, his parents’ hometown in central Taiwan. Yang’s father even narrates sections of the film in voice-over. Familial love letter it is. But letter to “every family that’s gone through this experience” is less obvious. The universality of how immigration can harden is not clear.

For one thing, Asian Americans have immigrated for other reasons. Many have not turned into the kind of father Pin-Jui becomes, yelling remorselessly at his young daughter to stop crying. In fact, the film’s depiction of Pin-Jui and Zhenzhen’s emigration from Taiwan in the 1970s does not feel well-researched, given the political context of that time, during which American immigration favored those with professional credentials or existing family ties.

The problem of aiming for universality is greater still: Tigertail feels torn between the universal and the personal; it has a tough time figuring out how to balance the before with the after, the Asian with the American.

Failing to Paint a Tiger

Sean Wang, a filmmaker at Google, says that he “really, really wanted so badly to love [Tigertail]” and that, all things considered, he did like it. Wang found it heartening to watch something “so proud of its Asianness” saying: “Just seeing it exist, being put out into the world at this time, was very comforting. I was rooting for it.” He admits, however, that the film’s scenes of the past — situated in Taiwan — were much stronger than those that take place in the present, in the United States.

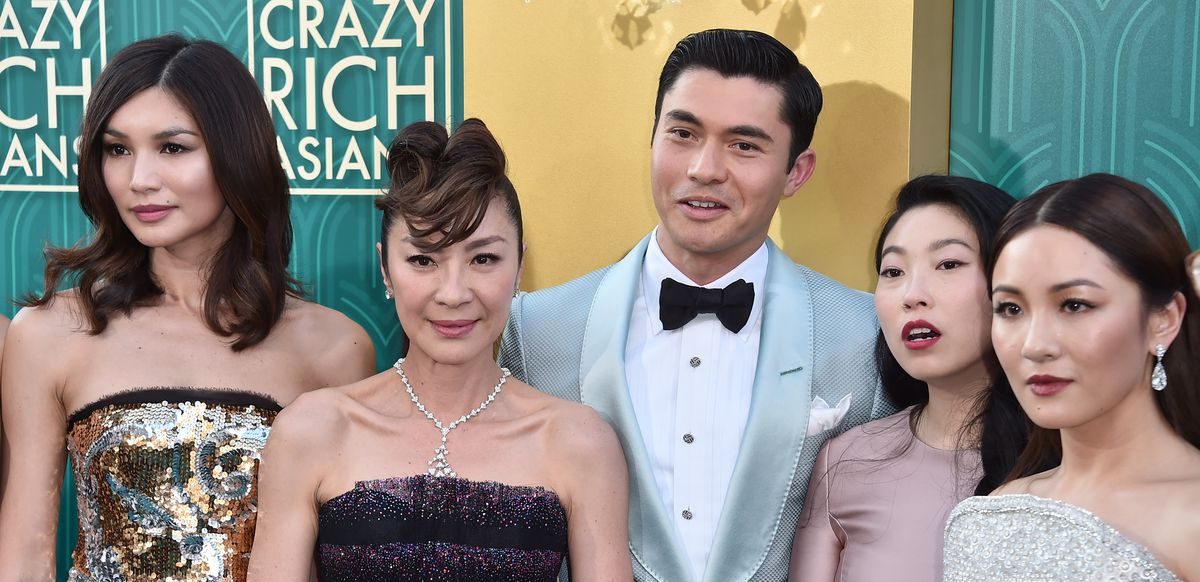

That Tigertail is split between the past and present, between Asia and America revisits questions that audiences and critics alike have been asking since the explosive release of Crazy Rich Asians in 2018. “The Asian American community is doing cartwheels [over Crazy Rich Asians] because our culture is being acknowledged. Only it isn’t,” journalist Sarah Lai Stirland wrote in The Boston Globe at the time. “It features one Asian American main character, representing one small part of the Asian diaspora in America. All the others are English-speaking Chinese from Singapore.”

Related:

Asia Reacts to “Crazy Rich Asians”: Asians, Americans, and Stars on Film’s ImpactArticle Aug 18, 2018

Asia Reacts to “Crazy Rich Asians”: Asians, Americans, and Stars on Film’s ImpactArticle Aug 18, 2018

Earlier last year, Lulu Wang’s The Farewell also contemplated — as Tigertail does — the idea of “going back” to Asia as a way to understand the pain, the severance, of immigration. When The Farewell was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the 2019 Golden Globes, debates ensued over what it meant to be a “foreign film,” given that Wang and much of her cast were American.

How can we consider Asian cinema together with Asian American cinema? This is something that Brian Hu, Assistant Professor of Film Studies at San Diego State University, has contemplated before. Hu points to Vietnamese American filmmakers, including Ham Tran, as examples of those who have gone to Asia to find stories, to mutual benefit. “Vietnamese American filmmakers went to Vietnam and transformed it,” Hu says. “They were pivotal in making Vietnamese cinema more international, and infusing [it] with new creative energy.”

Related:

“The Farewell” Gets Intimate with the Gaps Between Being Asian, Being Chinese, and Being AmericanThe critically lauded film humanizes the China where it takes place, giving Western viewers a fresh perspective on the countryArticle Aug 06, 2019

“The Farewell” Gets Intimate with the Gaps Between Being Asian, Being Chinese, and Being AmericanThe critically lauded film humanizes the China where it takes place, giving Western viewers a fresh perspective on the countryArticle Aug 06, 2019

Hu also notes that Tigertail is not the first film by a filmmaker who chooses to “go back” to Taiwan in the hope of telling a different story. In fact, the movie follows in the footsteps of the late great Edward Yang, who attended school and worked in the United States for many years before returning to Taiwan — and an auteur whom Alan Yang has cited as inspiration.

Sean Marc Lee, an American photographer currently based in Taipei, thinks that the influence of Hong Kong and the Taiwanese New Wave cinema — of which Edward Yang was a part — is visible, even too much so, in Tigertail. “It’s very surface-y, the way it’s approached,” says Lee. “It’s almost like, if he didn’t say anything about it, you wouldn’t hold it to those standards. Because once you start name-dropping those titans of cinema you’re like, ok, so am I supposed to approach watching your film from that same viewpoint?”

But Lee also makes room for a more empathetic understanding of the way Alan Yang drew upon his Asian influences, recognizing that he would have done something similar, in homage. “It’s like: I’ve been here before, I came to Taiwan, I know nothing about it, I was working on a movie here.”

Related:

Watch: Andrew Thomas Huang’s Sun-Drenched ’60s Short “Lily Chan and the Doom Girls”The film is a prelude to Huang’s surreal coming-of-age drama “Tiger Girl”Article Jul 01, 2020

Watch: Andrew Thomas Huang’s Sun-Drenched ’60s Short “Lily Chan and the Doom Girls”The film is a prelude to Huang’s surreal coming-of-age drama “Tiger Girl”Article Jul 01, 2020

Likewise, in The Ringer, Jane Hu posits that “Yang is not so much making independent Taiwanese cinema as drawing on its aesthetics to make what feels definitively like a new kind of American cinema,” and that the film is a “deliberate bridge between Asia and the United States, going a long way to make American film feel less local.”

By citing these giants of Asian cinema, Yang is also weaving them into mainstream American conversations. “As Asian Americans, we don’t really have cinematic masters the way that Taiwan does or Hong Kong does,” says Hu. “I mean, you can point to people — even Wayne Wang — but in terms of looking for masters, I actually like the idea that Alan Yang is trying to make an Edward Yang movie, as opposed to a Terrence Malick movie.”

“Ultimately,” he says, “what happens is that there will be people who will say I kind of like Tigertail — but I really want to know more about Taiwanese cinema.”

A Nose for Empathy

In May, Netflix dropped another quarantine hit: The Half of It, directed by Taiwanese American Alice Wu. Unlike Jon Chu, director of Crazy Rich Asians, or Alan Yang, Wu has been a well-known name on the Asian American indie film circuit for some time, celebrated for her 2004 feature Saving Face.

With The Half of It, Wu modifies the story of Cyrano de Bergerac to feature teenaged Ellie Chu, one of the only queer Asian American protagonists in recent memory. Ellie lives with her widowed, depressed father in a small town in Washington State, where she helps him with his duties as station master of their local train station. She is a straight A student and the only Asian at her school; she completes homework assignments for her classmates for extra pay. This is how Paul Munsky, an apparently typical jock from the football team, approaches Ellie, asking her for help writing letters to his crush, Aster Flores. The twist, of course, is that Ellie is also secretly in love with Aster.

But the other love story in The Half of It isn’t between Paul and Aster or Ellie and Aster but between Paul and Ellie: their initial letter-writing setup eventually blossoms into real friendship. Paul and Ellie accept each other for who they are, see beneath each other’s exteriors, and beyond easy stereotypes. Later, talking to Ellie’s father, Paul tells him that he doesn’t truly see his daughter: “What she is. Could be.”

What she could be — seeing the future in the present. “If I can get a 60-year-old, straight, conservative white guy to start identifying with a 17-year-old closeted Asian immigrant nerd or her depressed dad who’s lost the love of his life, I’ve won,” Wu told Variety. “Any time you can increase the human capacity for empathy, it’s a victory.”

Related:

“Don’t Tell Me I Can’t Do It”: Two Female Chinese Filmmakers on Awkwafina’s Oscar Shut OutWith Awkwafina and “The Farewell” both conspicuously absent from this year’s Oscars, we sit down to hear from two Chinese women in filmArticle Jan 28, 2020

“Don’t Tell Me I Can’t Do It”: Two Female Chinese Filmmakers on Awkwafina’s Oscar Shut OutWith Awkwafina and “The Farewell” both conspicuously absent from this year’s Oscars, we sit down to hear from two Chinese women in filmArticle Jan 28, 2020

Grand Designs

There is a phrase in Chinese: 画虎不成反类犬. Hua hu bu cheng fan lei quan. Meaning: failing to paint a tiger and ending up with a dog instead. The ancient origin of this saying had to do with one’s character: Ma Yuan, a respected general in the Eastern Han Dynasty, told his nephews not to emulate someone too heroic and accomplished, for, if they failed, they would end up as caricatures or worse.

Modern usage of this has instead largely centered around visual or visible likeness — think “Ecce Mono”; think aspirational, think someone literally trying to paint something grand and coming up short. Tigertail attempts to paint a tiger — or maybe Edward Yang? — in more ways than just its title, and comes up short, but it is heartening to remember that it is only a debut. Nor is it alone among recent mainstream films in feeling out their lineage in Asian and independent Asian American cinema.

And just how might we better communicate that genealogy, that community?

“Well, that’s kind of my lifelong mission,” says Hu, with a laugh. “As a critic and with my scholarship.” He also reminds his students, many of whom are on the production rather than the critical side of film, that “Creation is also a work of criticism. Their films can help us see the world anew.”