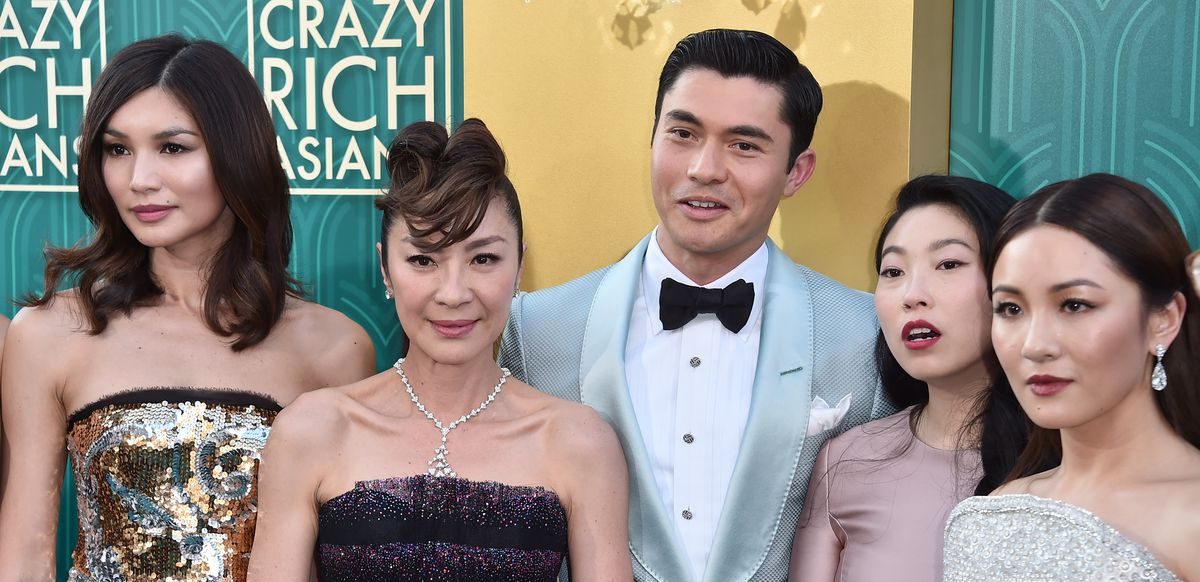

This Wednesday, a cinematic shockwave made its way through the US Asian-American population, in the form of director Jon M. Chu’s film version of Kevin Kwan’s Crazy Rich Asians. The film will be the first Hollywood offering to feature a predominantly Asian cast with Asian leads in over two decades (the last movie to fit that description was Amy Tan’s “Joy Luck Club” in 1993). It’s also stacked with recognizable stars like Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon’s Michelle Yeoh, and Fresh off the Boat’s Constance Wu.

These past few years have been particularly egregious for Asian representation in Hollywood, with Rupert Sanders’ Ghost in the Shell, Zhang Yimou’s Great Wall, and countless others all falling victim to whitewashing of lead actors. A successful box office for Crazy Rich Asians could be the litmus test to dismiss the constant suggestion that “Asian actors aren’t marketable” (although as many have also pointed out, if the film “fails” it would be unfair to assume the Asian-ness of its cast as the reason for this).

Meanwhile, though, in China, excitement is minimal. The film hasn’t gotten the green light for a Chinese release, but if it does (and at present that seems unlikely), its biggest selling point in the US will mean very little for Chinese viewers. Nearly every film in China features an all-Asian cast, and an all-ethnically Han Chinese cast at that. It’s a Hollywood film, but without the box office sheen of Optimus Prime or Robert Downey Jr.

China writer Rui Zhong pointed out some differences between the two audiences’ viewing criteria on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/rzhongnotes/status/1027743839455465474

And yet, despite huge gaps in understanding, there is a sense of identity and common struggle running between young Chinese and Asian-Americans as the film rolls out.

“A lot of people missed the point about the significance of this movie, with an all-Asian cast, and didn’t understand the Asian-American perspective of it, or the struggle to be both Asian and American at the same time,” one Weibo commenter wrote. “Many of my American-born Chinese friends cried last night.”

Another wished for a strong box office performance:

“I hope that this movie is successful. If this one is a success, Warner Brothers could green light four other Asian films, and Asians will have more room to develop.”

“Yes, at least it proves that Asian actors also have a market,” another agreed. “Asians are working hard in Hollywood.”

Several Douban comments referenced The Joy Luck Club while discussing the potential impact of Crazy Rich Asians

On the overwhelmingly young and hip social media platform Douban, the film holds an early rating of 7.1 stars, and the comments section is alive with discussion. Some commenters aren’t impressed (“my only gripe is that the setting is Singapore…why not our country?” someone laments), while others push to look past initial criticisms:

“White movies only need to tell a story — why should we demand this film represent all the complexity of Asian culture?” reads the top-rated comment. “It’s important now to drop our pet peeves, and support the opportunity to see more Asian stories at the box office.”

The nail-biting and finger-crossing among Asian-Americans seems audible to many in China, especially to millennials. Young Chinese are more open minded and boast more international understanding than their parents — they’re more likely to have studied overseas, or to have consumed Hollywood movies and Western media from a young age, and to sympathize with the plight of Asian-Americans searching for representation.

Asian-Americans on the other hand, like all Americans, are likely to grow up on a diet that is largely Hollywood blockbusters, supplemented by sporadic Taiwanese dramas or Korean movies playing on laptops and family TV sets. They’re more aware than anyone of the disparity in representation when it comes to white versus Asian, and it stings them hardest when they have to watch another powerful, complex Asian role be re-written for a white guy. For them, seeing an all-Asian storyline — played out by an all-Asian cast, if you can believe it — is unspeakably empowering.

“It’s not just about obscene wealth — it’s about unapologetic Asians who don’t need to prove themselves to anyone,” says Amy DeCillis, born in Hunan and raised by adoptive parents in the States, and now studying Interactive Media Arts and Global China Studies at NYU Shanghai. “It’s showing the world that Asian actors and actresses can be the rich and powerful main character, and not just the sidekick or the nerd.”

2011’s The Green Hornet managed to successfully cast Taiwanese pop legend Jay Chou for the role of Kato, originally played by Bruce Lee — though of course, still in the position of kung fu sidekick.

In addition to the all-Asian cast, Crazy Rich Asians also break serious ground by portraying an (admittedly exaggerated) slice of life storyline. Whereas before, Asian audiences had to settle for excitement at the prospect of The Green Hornet’s kung fu sidekick Kato being faithfully portrayed as a sexy Asian man, Crazy Rich Asians puts Asians on the big screen as professors, boyfriends, fiancées, business tycoons, sons, and mothers. The heroine is a funny, real Asian woman, not an exoticized and eroticized sex device. Her love interest is an attractive Singaporean man, an otherwise classic rom-com male lead, who doesn’t know any martial arts.

In terms of Asian representation, a well-constructed female lead and a leading man with sex appeal are both huge leaps for the industry.

Related:

BRICS Film Co-Production “Half the Sky” Focuses on Women’s StoriesArticle Jun 20, 2018

BRICS Film Co-Production “Half the Sky” Focuses on Women’s StoriesArticle Jun 20, 2018

Still, some Asian viewers have voiced criticism. Crazy Rich Asians takes place in Singapore, an incredibly ethnically-diverse country. While approximately 75% of its 5.6 million residents are of Chinese ethnic descent, the other 25% is made up of a diverse blend of Malays, Indians, and other ethnic groups. With its highly-touted “all-Asian” cast, some viewers were displeased with the overwhelmingly Chinese-ethnic take on the word “Asian.”

“Part of the way that this movie is being sold to everyone is as this big win for diversity, as this representative juggernaut, as this great Asian hope,” Singaporean Indian writer and activist Sangeetha Thanapal told the New York Times. “I think that’s really problematic because if you’re going to sell yourself as that, then you bloody better actually have actual representation.”

Star Constance Wu, who plays Rachel Shu in the film, addressed those concerns in a Twitter post. “So for those of you who don’t feel seen, I hope there is a story you find soon that does represent you,” she wrote. “I am rooting for you.”

#CrazyRichAsians opens August 15th. Read below to understand why it means so much to so many people. All love. @CrazyRichMovie @FreshOffABC @WarnerBrosEnt pic.twitter.com/IISLRDMRjU

— Constance Wu (@ConstanceWu) August 1, 2018

There are valid truths to that critique, and the multidimensional story of “Asian” people is an important one to tell. But the overwhelming sentiment seems to be that Crazy Rich Asians has succeeded where some feared it would fail, and surpassed what many viewers would have considered acceptable.

“Yes, the story only highlights rich East Asians, but it was never the film’s goal or responsibility to represent all Asians,” says DeCillis. “And how could it? Asians are not monolithic, and one film could not possibly encompass all of the different Asian identities. This movie isn’t the end-all-be-all of Asian films in America, and that’s a good thing, because it’s set the stage for more stories to come.”

[pull_quote id=1]

Mark Lee, Research Manager at entertainment market research company Screen Engine/ASI, points out that the desire for perfect representation has to be balanced with the realities of film production.

“It goes back to expectations – they are high and everyone wants to see a bit of themselves on screen, when that’s unrealistic and impossible. Imagine going to every film with an all-white cast and demanding that it represent people from extremely liberal San Francisco, to deep country South in Mississippi, and demanding the director cast someone from every part of the country with ancestral roots going to all different parts of Europe.

It’s noble, but not feasible, and at some point you have to draw the line and say, ‘Look, this is the best we can do without having quality of the actual story or production suffer.’”

For Singaporean actress Victoria Loke, whose role as Fiona Cheng in Crazy Rich Asians was her first time on the big screen, that balance was especially important.

“Singapore is such a unique melting pot of indigenous and settler cultures, and to represent a country like this requires a sensitivity to the nuances of these intersections, and how they are very much different from their cultures of origin,” she tells RADII.

“I cannot emphasize enough just how much thought and effort was put in behind-the-scenes to make this possible: our production designer Nelson Coates did a fantastic job right down to the tiniest little kuehs and must-have nyonya ingredients that would dress the kitchen of the Young family’s Peranakan household, which he learned about by personally speaking to the food stall aunties at the local markets.

“If you listen closely, you will hear that Singaporean accents fill the background in the movie; if you take a second look, you will also see that the extras are dressed not just in cheongsam but in saris and baju kurung and kebaya. A lot of our crew members were local, and their input was invaluable to the production too.

“As much as this is an American production, there was a conscious and continuous effort to engage with the local community and have those perspectives inform the representation of Singaporean culture. That’s something I consider crucial to representing cultures that are different from your own.“

[pull_quote id=2]

As for the film’s reception in Asia, versus in the States, Loke sees the amount of media coverage and online commentary that the movie has sparked on the continent as a positive development.

“There have been a lot of discussions sparked in Asia with the release of the trailer, which is indicative of the emotional ownership that people already have of this film, and that is a compliment in a way,” she says. “I think critical engagement with the media we consume is important, and I also think that the engagement in this particular case needs to be informed by an awareness of the differences between the Asian-American experience and the experiences of the rest of the Asian diaspora.”

Ultimately, it comes back to the idea that Crazy Rich Asians should not be seen as a representation of some unified Asian experience, she says. “Being a Chinese person in China is very different from being part of the Chinese diaspora in Singapore, which is also very different from being part of the Chinese diaspora in America. I believe the challenge for Asian audiences would be to momentarily suspend their own cultural biases when engaging in their critique of the film, and to use this film as a vehicle to understand the Asian-American experience, and the multiple iterations of Asian identity.”

Related:

Meet the New Wave of Chinese FilmmakersArticle Aug 02, 2018

Meet the New Wave of Chinese FilmmakersArticle Aug 02, 2018

Crazy Rich Asians may not be perfect, but then again, nothing is. The film succeeds not only in hosting an all-Asian cast (easier said than done, considering one producer tried to suggest casting heroine Rachel Shu as a white woman), but in its execution as a film. It is, by all accounts, a funny, nuanced, and rather true-to-life representation of Asian humans, marching forward out of a sea of kung fu villains and geishas.

Kevin Kwan and Jon M. Chu were right to turn down the offer of a huge payday from Netflix, in favor of putting their vision on the big screen. It may not turn out to be a smash hit with Chinese/Asian audiences, or event to secure a screening here in China, and it may not perfectly represent the setting of Singapore. But the film is indeed a watershed moment for Asian-Americans, and for Hollywood itself, and that impact can be felt and understood by Asian audiences worldwide.

You might also like:

China’s Hottest Female Rapper Makes Hollywood Debut on “Crazy Rich Asians” SoundtrackArticle Aug 15, 2018

China’s Hottest Female Rapper Makes Hollywood Debut on “Crazy Rich Asians” SoundtrackArticle Aug 15, 2018

Toronto’s Newest Film Fest Wants to Show “the Real, Unfiltered Picture of China”Article Jul 25, 2018

Toronto’s Newest Film Fest Wants to Show “the Real, Unfiltered Picture of China”Article Jul 25, 2018

Has China’s Most Expensive Ever Film Become its Biggest Ever Flop?Article Jul 17, 2018

Has China’s Most Expensive Ever Film Become its Biggest Ever Flop?Article Jul 17, 2018