“Besides the Xinhai Revolution of 1911, this is the second time the world has heard of Wuhan.” This is what a friend in Wuhan told me in the wake of the coronavirus crisis, which has unfortunately made the capital of Hubei province famous worldwide. But Wuhan is not only the epicenter of the recent virus outbreak, it’s also a complex and beautiful city, which has a long history of revolution and dissent — and of great music.

On October 10 1911, the Wuchang Uprising led to the establishment of the Republic of China and the downfall of the Qing dynasty. In 1967, at the height of the Cultural Revolution, an armed conflict later dubbed the “Wuhan incident” was a turning point for the Communist Party. And in the mid-1990s, Wuhan was again at the epicenter of another revolution: the Chinese punk movement.

Related:

Keep Screaming: A Brief Account of Early Beijing PunkA story of distorted guitar, roast duck restaurant basements and beers. Lots of them.Article Jan 22, 2020

Keep Screaming: A Brief Account of Early Beijing PunkA story of distorted guitar, roast duck restaurant basements and beers. Lots of them.Article Jan 22, 2020

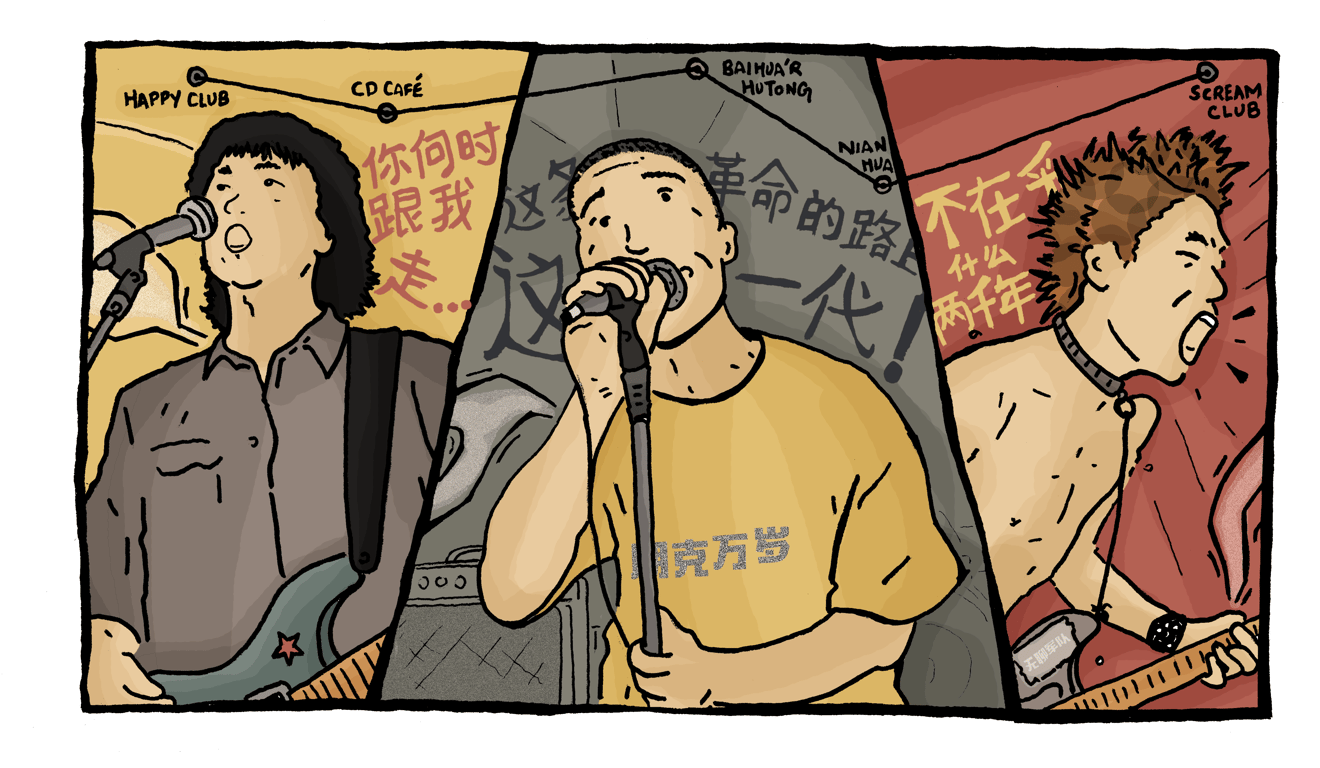

I’ve previously written about the Beijing punk rock movement of the mid-1990s, led by underground bands like UnderBaby, Catcher in the Rye, and, later, by the “Boredom Army,” Wuliao Jundui. Beijing punks were backed by the rock community flourishing there in the 1980s. But 1,000 kilometers south of the Chinese capital, the city of Wuhan was at the same time also witnessing the birth of a punk subculture.

Who was first, Beijing or Wuhan? This is a very controversial question, as both cities claim to have given birth to Chinese punk. As always, the issue is more complex than it appears; the answer is not merely chronological, but also involves ethics and politics. Claiming that Wuhan is the true birthplace of Chinese punk means one favors political engagement over style, raw punk energy over complex musical arrangement. I am myself non-objective on the matter, as shown by the tattoo on my upper arm or the patch sewn on my jacket: I frankly lean toward Wuhan. For me, if there is one song that embodies Chinese punk, it’s not “All the Same” (都一样), the self-proclaimed “first Chinese punk song” by UnderBaby; it’s “Scream For Life” by SMZB. Here’s why.

Claiming that Wuhan is the true birthplace of Chinese punk means one favors political engagement over style, raw punk energy over complex musical arrangement

Along with rebellion, Wuhan is known for culinary delicacies like the fabulous “hot and dry noodles,” (reganmian; 热干面) and delicious duck necks (yabozi; 鸭脖子), as well as unbearable temperatures and humidity in the summer and winter. One of the most interesting punk scenes in the country was born in this cauldron in 1996 with the formation of SMZB (the band’s name stands for shengming zhi bing, 生命之饼 — literally “the bread of life,” a reference to the Bible) by Wuhan-born singer and bassist Wu Wei.

Wu grew up in a complicated family in the district of Hankou, hanging out on the streets with petty criminals and stirring up trouble at school. In Never Release My Fist, a documentary by Wang Shuibo, Wu recalls witnessing blatant injustices in his youth. The sound of early SMZB was heavily influenced by street punk, with very basic melodies, fast tempos and crude lyrics. The arrival of a new band member playing flute and bagpipes would help the band land on their signature Celtic punk sound in the 2000s, but if you want to understand the earlier SMZB sound, you can listen to their first cassette tape, self-released in 1999, entitled “Damn You” (你是该死的):

At some point, Wu Wei discovered that in Beijing, a new school of music was accepting students who didn’t need to pass the gaokao, the Chinese university entrance exam. The Beijing Midi School of Music, which is now well known around the country for its annual Midi Music Festival, allowed Wu to develop his musical skills and meet the musical underground of the Chinese capital. Unlike Beijing, Wuhan had no underground live venues or an older rock community to help young punk bands perform — before coming to Beijing, Wu Wei had no idea about pioneering rockers like Cui Jian.

Rather than pursuing a subcultural career in Beijing, however, Wu decided to move back to Wuhan after his time at Midi with friend and SMZB drummer Zhu Ning, in order to help Hubei’s capital develop its own punk scene. Wu Wei was also involved in the development of punk scenes and live venues in other cities, like Changsha and Guilin.

Related:

Yin Special: Wuhan RocksWith the city in the headlines, here’s a reminder of Wuhan’s rich musical heritageArticle Jan 31, 2020

Yin Special: Wuhan RocksWith the city in the headlines, here’s a reminder of Wuhan’s rich musical heritageArticle Jan 31, 2020

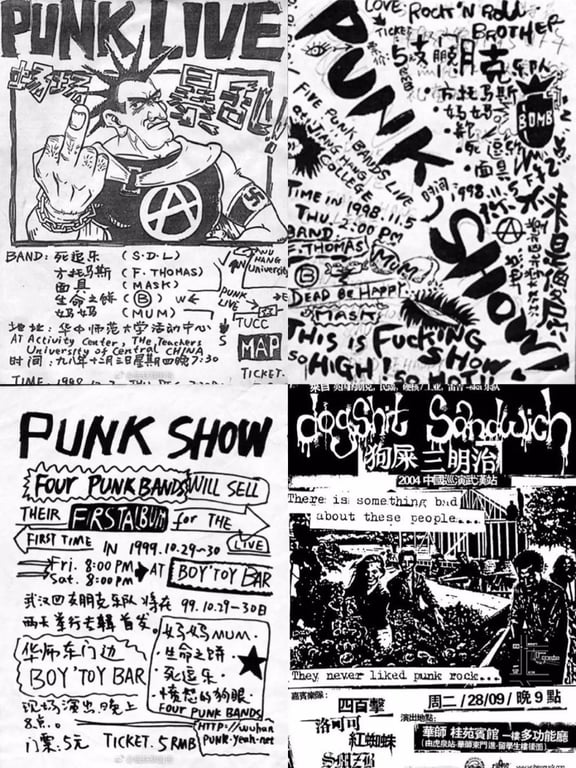

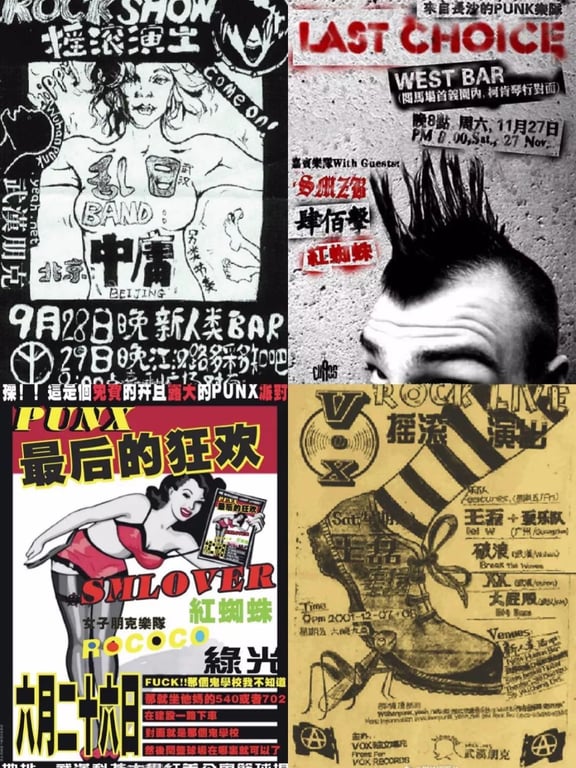

SMZB was of course not the only band in Wuhan. Soon after SMZB started, several other punk bands began to form, sharing members and instruments. Zhu Ning himself had to play drums for six bands. SMZB was soon joined by bands like Si Dou Le (死逗了), MUM (妈妈), F. Thomas, Mask (面具), Angry Dog Eyes, Big Buns, and Disover. Contrary to Beijing, Wuhan punks had to create their own spaces to perform and rehearse, first playing at universities (at the activity center of Wuhan Normal University, for instance) and KTVs, or karaoke bars. As Wu Wei recalls: “We had to negotiate with KTV owners, but after we played in one KTV, they wouldn’t want to have us again, and we had to find another one!”

Most of the punks in Wuhan came from a working-class background, unlike the more “middle-class” upbringing of Beijing punks, and they were not afraid to steal their food, beer or their musical instruments in order to survive

Wuhan punks didn’t have bars owned by rockers like in Beijing, but they had something else: links to the underworld of the Hubei capital. They could find spaces not directly controlled by the authorities, and thrive in the underground. Most of the punks in Wuhan came from a working-class background, unlike the more “middle-class” upbringing of Beijing punks, and they were not afraid to steal their food, beer or their musical instruments in order to survive.

The favorite sport of Wuhan punk was — and still is — running naked on the streets (luoben, 裸奔) after drinking, often chased by the police. As sung by SMZB in 2014, they are the “Naked Punks,” both literally and figuratively: they truly had nothing to their name.

Early Wuhan punk posters

Wuhan punks could not continue performing in universities, where the administration often cut their power because of the noise, nor KTVs. They had to open their own venues.

Kang Mao, now the singer of the Beijing punk band SUBS, opened the bar Boy Toy with two friends, which promptly began organizing punk shows. Kang Mao herself created her own all-female punk band, No Pass, with Hu Juan, who would later become SMZB’s drummer and Wu Wei’s first wife. Zhu Ning decided to help the scene by creating a live venue dedicated to underground music: VOX, which is still today the epicenter of the musical underground of the region. VOX’s motto “Voice of Youth, Voice of Freedom” still defines the scene in Wuhan.

One important characteristic of the Wuhan punk scene is its politicization. Wuhan punk bands in general, and SMZB in particular, don’t hesitate to tackle very sensitive topics, from Tiananmen to Mao’s cult of personality, police brutality, or petitioners. Having a political stance as a musician can be risky: in December 2017, someone complained about the band on a Beijing municipal website, inviting unwanted attention to their performance. As SMZB sung on their 2002 EP Wuhan Prison, Wuhan punks “don’t just say ‘fuck’” — they put actions behind their words. In Wuhan, punk is something serious, as shown by the other key figure on the Wuhan punk scene, Mai Dian (麦巅), who used to play in Si Dou Le and later formed the band 400 Blows (四百击).

Mai Dian opened an autonomous youth center in the Donghu area of Wuchang district in the east of the city called Our Home (我们家), based partly on the squats he experienced when touring in Europe with his band. Now closed, Our Home was an oasis of liberty in the sometimes suffocated city of Wuhan, where people hung out, played music, drank beers, and organized talks and film screenings.

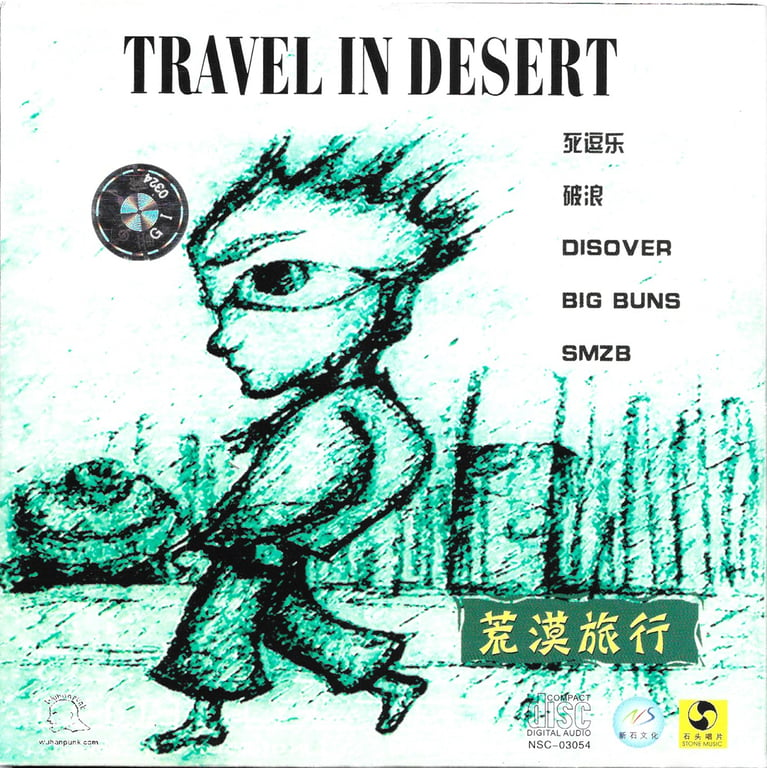

Travel in Desert was an early compilation of Wuhan punk featuring Si Dou Le, SMZB and others

In their songs or actions, Wuhan punks often show their affection for the city, but also their aversion to a municipal government that tries to suppress every inch of popular autonomy. On Wuhan Prison, Wu Wei compares the city to an open-air prison:

I am living in the city, with my family

We can’t feel freedom and safety

We feel like [we’re] in a prison

I want to leave this hell, but can’t find a way

So many fucking rules, but I don’t care

Riot, riot this city… Wuhan Prison

Wuhan Prison is also the name of a bar managed by Wu Wei, located just downstairs from VOX Livehouse in Wuchang. Apart from being the coolest bar on earth, it is the meeting place of the Wuhan musical underground. “One Night in Prison” (贻笑大方) by SMZB aptly describe the atmosphere of the bar:

In 2008, SMZB released a now-classic album through the label Maybe Mars for their 10 years anniversary (in fact 12, but never mind), Ten Years Rebellion, including the song “Great Wuhan” (大武汉). The song is a love letter from Wu, who wishes that his hometown will gain freedom one day, “because it belongs to you and me.” One has to see SMZB perform this song in Wuhan, at VOX, to understand the influence of SMZB in this city. For me, Wuhan will forever be associated to this song, virus outbreak or not:

I was born here, this hottest city,

800 millions people live here,

In 1911, the Wuchang Uprising fired here,

Sun Zhongsan [Sun Yat-sen] is always kept in my mind,

I live here with my dream,

I walk on the street with my hope,

I want to change this city,

Because she belongs to you and me;

She will be beautiful, she will get freedom,

It won’t be like a prison here forever,

Break the darkness, there will be no more tears,

A seed has been buried in my heart.

Here is a punk city, Wuhan!

We sing this song for you, Wuhan!

We start to rebel and fight in Wuhan,

Everybody cheers for you!

Wuhan punks have shown that they do care about their city, and try to protect it themselves. They were were greatly involved in the defense of Donghu, Wuhan’s East Lake neighborhood, after a scandal broke out in 2010 — revealed by Time Weekly (时代周报) and the Southern Weekly (南方周末) — about a corrupt development project in the area, where a lot of punks live. In a 2014 interview, Wu Wei explains how they tried to resist the expropriation of the Donghu area, and were harassed by the local authorities. Mai Dian continued the good fight by organizing talks about Donghu and forming an art collective to document the real estate development. In 2015, filmmaker Luo Li released a fascinating movie about East Lake, Li Wen at East Lake (李文漫游东湖), featuring a lot of Wuhan punk figures, including Wu Wei and Mai Dian.

Throughout the years, Wuhan has produced a huge number of great bands, well-known or not, and several music compilations are now the last testimony of the city (sub)cultural creativity, such as 2003’s Travel in Desert (荒漠旅行), which featured five Wuhan early punk bands.

Through his label Wuhan Prison Records, Wu Wei has also produced several compilations of Wuhan bands, such as Pepsi Punk (百事朋克) in 2010, and the 2011 folk compilation The Temperament of the Punk Youth (文艺气质的朋克青年). VOX and Zhu Ning have, since 2013, released four compilations of Wuhan rock and hip hop entitled Voice of Wuhan (武汉之声). All the artists featured are worth checking out: The One, 757, Sharpills, Mean Street, BigDog, Meat Sucks, Codnew, 不三不四. Among all these, perhaps the most well-known is the post-punk band AV Okubo, whose members include the drummer Hu Juan, as well as the very promising post-rock band Chinese Football. (You can listen to both here.)

In 2015, independent filmmaker Wang Shuibo released an incredible documentary on the Wuhan punk scene entitled Never Release My Fist (绝不松开我的拳头), a reference to an SMZB song. For me, this is the best documentary on Wuhan and on the underground Chinese music scene in general. Wang Shuibo let the Wuhan musicians speak and tell their stories in their own words. Watching the film, one also learns how to open a pizzeria with drug money.

I’ve worried about my friends in Wuhan every day since the virus outbreak. I know they are fine for now, confined in their homes, eating instant noodles instead of “hot dry noodles,” playing songs at home, and living in a real-life “Wuhan Prison.” But I also know that if there is one place that can beat any kind of virus, it’s Wuhan, a rebel city that saw the real birth of Chinese punk, against all odds.

Wu Wei recently sent a letter via Unite Asia, a website dedicated to the Asian underground scene run by Riz Farooqi of legendary Hong Kong hardcore band King Lychee. (Here they are covering SMZB’s “Scream for Life.”) Wu states that he and the band are fine. And, ever politically conscious, he takes the opportunity to state his support for Hong Kong — because if there’s one band who has the guts to tell the truth, it’s SMZB, from Wuhan.

You might also like:

Hang on the Box: The Illustrated Story of China’s Female Punk PioneersThe story of self-described “bitch-punk” band HotB, who were determined to break through the Beijing cultural underground’s glass ceiling in the late ’90sArticle Sep 04, 2019

Hang on the Box: The Illustrated Story of China’s Female Punk PioneersThe story of self-described “bitch-punk” band HotB, who were determined to break through the Beijing cultural underground’s glass ceiling in the late ’90sArticle Sep 04, 2019

The Great Chinese Rock ‘n’ Roll SwindleHow a postmodernist trickster convinced the world that punk rock had reached China in the early ’80sArticle May 13, 2019

The Great Chinese Rock ‘n’ Roll SwindleHow a postmodernist trickster convinced the world that punk rock had reached China in the early ’80sArticle May 13, 2019