In a previous article for RADII, I talked about the birth of Chinese punk — or more precisely, the birth of a fake Chinese punk band. Let’s continue the story of Chinese punk with its apparition in Beijing, a decade after Marc Boulet invented the Dragons.

The Great Chinese Rock ‘n’ Roll SwindleHow a postmodernist trickster convinced the world that punk rock had reached China in the early ’80sArticle May 13, 2019

The Great Chinese Rock ‘n’ Roll SwindleHow a postmodernist trickster convinced the world that punk rock had reached China in the early ’80sArticle May 13, 2019

A quick note up front: in this article I’m talking about Beijing punk. I cannot stress this enough: only Beijing, which does not represent the whole of China. There is an ongoing debate between Beijing and Wuhan camps about who qualifies as the first Chinese punk band. This article doesn’t take a side — its only purpose is to tell the story of early Beijing punk, and its connection to China’s older rock’n’roll community. It’s a story of distorted guitar, roast duck restaurant basements and beers. Lots of them.

Chinese Rock in the ’90s: Between Crisis and Survival

In the 1990s, Chinese rock’n’roll was in a state of existential crisis. Theses have been written on the “crisis of Chinese rock”; Andrew F. Jones also published an influential book in 1992 regarding Chinese rock. All of these analyses pointed towards the progressive disappearance of Chinese rock after 1989, in a context of political and cultural repression.

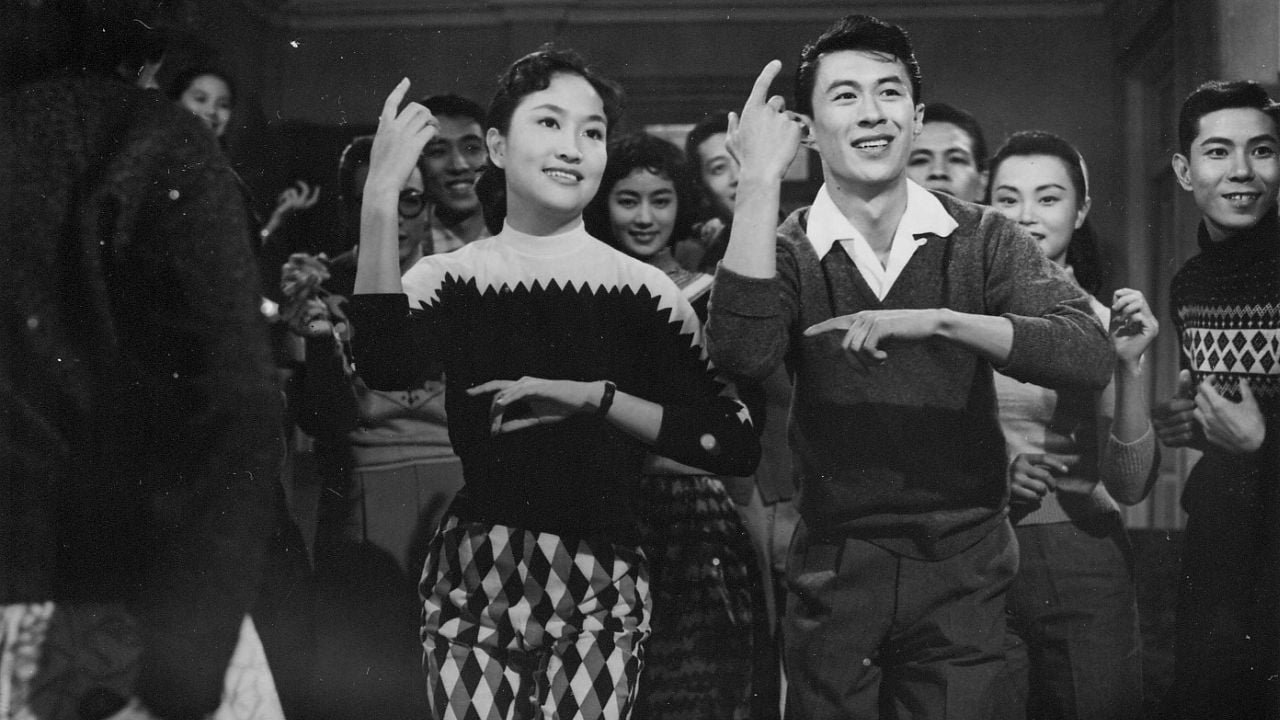

Chinese rock, which dates back to 1979 with the creation of rock cover bands among both Chinese (Wan Li Ma Wang) and expats (the Dalu Yuedui), hit the mainstream in 1986 when Cui Jian performed “Nothing to My Name” on national television at a charity concert in Beijing Worker’s Stadium. The sound, the guitar, Cui Jian’s voice, and even his socks were something entirely new for a lot of Chinese. Hailed as the “Godfather of rock”, Cui Jian was the voice of Chinese youth in the 1980s, and his 1989 album, Rock ‘n’ Roll on the New Long March is still considered the best rock’n’roll album from China.

In 1984, Cui Jian’s sound, guitar, voice, and even his socks were something entirely new for a lot of Chinese

Related:

“My Dad’s a Rocker” Tells the Story of a Chinese Rock ‘n’ Roll PioneerArticle Mar 26, 2018

“My Dad’s a Rocker” Tells the Story of a Chinese Rock ‘n’ Roll PioneerArticle Mar 26, 2018

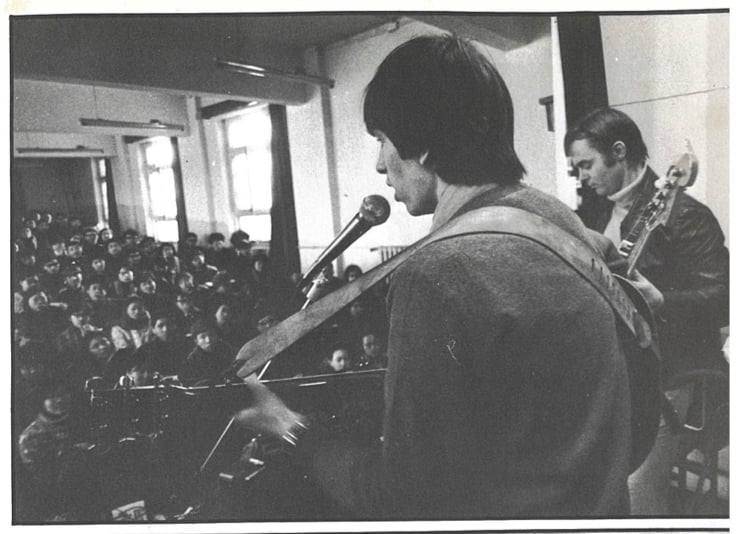

To perform live, rock bands in the 1980s didn’t have much choice. They could organize a show in a university — providing that the administration would let them — or play in international hostels during “parties,” mostly frequented by expats, as highlighted by Catherine Capdeville-Zheng in her work on Beijing rock circles.

Expat rock band All Star Beijing performing at Beijing Teacher’s College in 1981, in Liu Heung Shing (from China After Mao, Penguin Books, 1984)

In a book published in 1993, Xue Ji tells the story of these “parties” — the English word was used for early gigs, rather than “performance” or “show,” or even the Chinese word for “party” — first organized by Beijing expats, and progressively opened to Chinese rockers. Cui Jian was the first Chinese rocker to perform at a party at the restaurant Maxim’s in 1986. Li Ji, the singer of the rock band Bu Dao Weng, was the first Chinese rocker to organize a party two years later, in a karaoke on the Western side of the capital, but after 1989 it became more and more difficult to organize these kinds of events in Beijing. Cui Jian himself was eventually banned from playing live concerts in the city, even though he agreed to organize a nationwide tour in 1990 to promote the Asian Games, as noted by Jonathan Campbell in his book Red Rock.

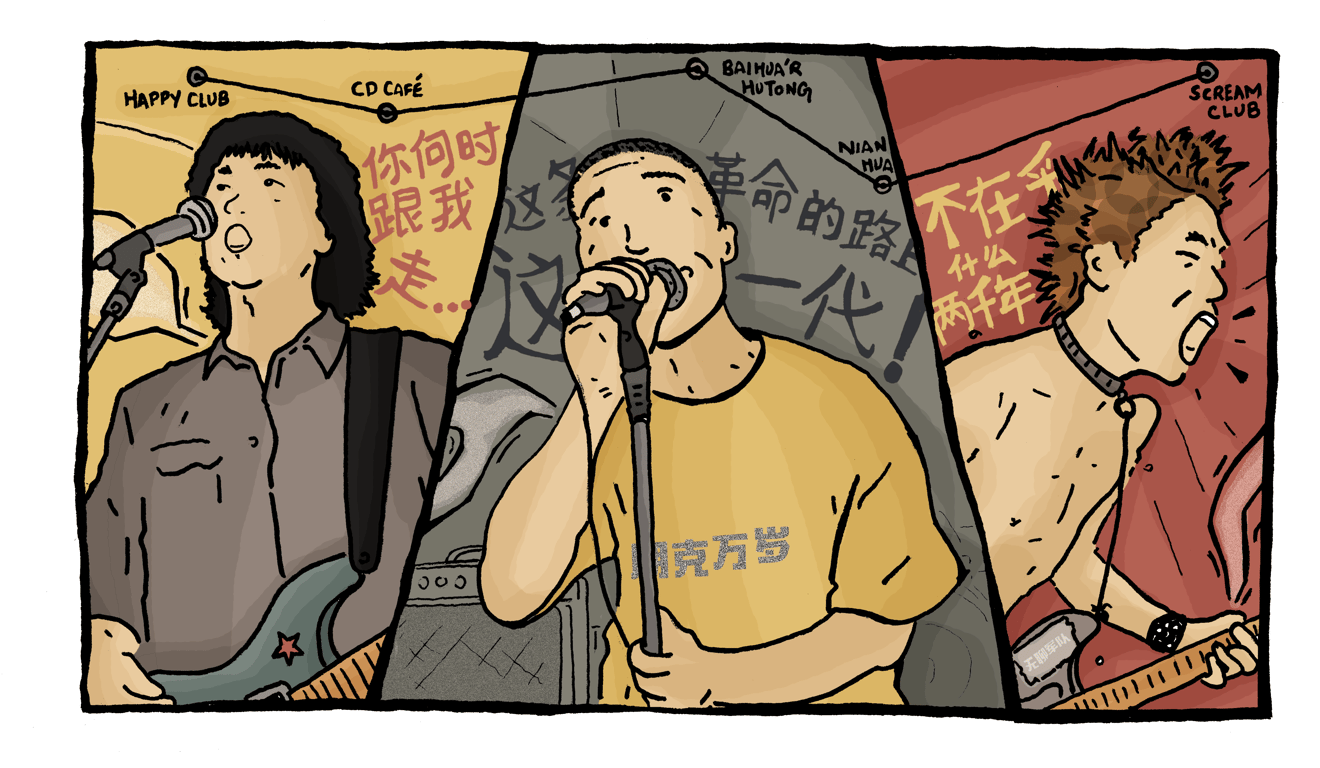

In 1992, Li Ji opened the first space dedicated to rock parties: the Happy Club (Xingfu Julebu), but due to pressures from the authorities, he had to close it down in 1993. Other bars and clubs opened at the same time, to host a growing rock circle in the capital. Liu Yuan, Cui Jian’s trumpet player, opened CD Café, a bar and live venue, where rock musicians like Cui Jian could play, even if they don’t have official approval. A very interesting interview with Cui Jian by BBC World in 1995 captures the schizophrenia of official censorship: Cui Jian learns that his concert in Taiyuan is unexpectedly canceled by the authorities. His reaction cannot be clearer: “我操! 真那么傻逼” (“Fuck! What a bunch of dickheads”). At the end of the footage, Cui Jian goes to CD Café to play the saxophone, in a safe environment in the middle of Beijing.

Children of Dakou

If Chinese rock’n’roll was in the middle of an existential crisis in the early ’90s, supposedly being replaced by Canto- and Mando-pop, rockers still continued to exist in the underground, taking advantage of the spaces they occupied in the 1980s and the sociability they created. By the mid-1990s, the Beijing rock community possessed all the resources necessary to organize a concert, and a new generation of young musicians appeared all around China.

Unlike the rockers of the 1980s, who grew up in music-oriented families (Cui Jian’s dad was a musician in the People’s Liberation Army; members of Bu Dao Weng studied music at university), this new generation was largely self-taught, and was introduced to rock and punk music by other means. Instead of listening to Cui Jian’s songs, the ’90s kids were buying pirated CDs of Hong Kong rock band Beyond, and most of their musical education was made through dakou and pirated CDs and tapes.

For the Beijing punk kids, the rock community of the 1980s was essential, because the rockers possessed the resources they needed to organize concerts. They had bars, instruments, ways of dealing with the local authorities. The Gao brothers, founders of the early punk band UnderBaby (which pretty much looked like a grunge/garage band), participated in rock parties in the early 1990s, and performed for the first time at a rock party. A younger generation of grunge rockers, like The Fly and Catcher in the Rye, performed with UnderBaby at CD Café and Angel’s Bar, where you could see Cui Jian and his band in the audience. UnderBaby published its first punk song, “All the Same,” in 1996 in the rock compilation China Fire II, alongside rock legends Dou Wei, Zhang Chu and Iron Kite.

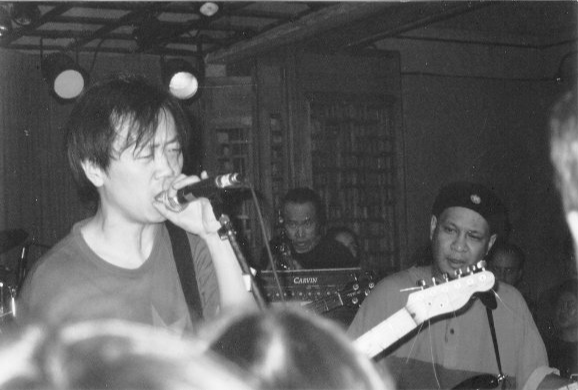

Cui Jian singing at the CD Café, 1997 (photo by David O’Dell in Inseparable: The Memoirs of an American and the Story of Chinese Punk Rock, 2014)

But punks also needed their own space, to hang out and rehearse. And that’s what the brothers Gao from UnderBaby provided, perhaps unwillingly, when they turned the tiny annex of their parents’ roast duck restaurant in Baihua’r hutong into a rehearsal space. As noted by David O’Dell in his memoir Inseparable, the tiny room was the epicenter of the early Beijing punk community. People came and people went, practicing their instruments, drinking cheap beers, fighting, creating new bands, disbanding old ones, making love… This tiny room was the petri dish of the coming punk bands, which would shape the Chinese punk sound over the following decades.

UnderBaby posing for a photo at their rehearsal space at Baihua’r hutong, 1996 (photo by David O’Dell in Inseparable)

These newly-formed bands booked shows in newly-opened bars, karaoke parlors, and universities. The bar Nian Hua (also known as “Here and Now”), opened by the artist Song Xin, was for a brief moment the meeting point of the Beijing alternative scene. In February 1997, for a Valentine’s Day concert, David O’Dell took footage of the show revealing the porous nature of the relations between the 1980s rockers and the young Beijing punks.

During the show, the street-punk band 69 performed in front of a very diverse crowd. You could see members of Cobra, the first all-female rock band of the 1980s, UnderBaby, Catcher in the Rye, but also Dou Wei himself, the ex-singer of China’s first hard-rock band, Black Panther. Dou was one of the first experimental musicians in China, and his former wife, Wang Fei (Faye Wong), was a Cantopop and Mandopop musical icon who at the time combined pop and alternative music, showing the links between these two musical worlds.

All of these genres and generations coexisted together in the same physical space, because the punks needed these rock bars to perform. But they were soon able to open up their own venues.

Scream Club: Beijing Punk Paradise?

The year 1998 represents a turning point for the nascent Beijing punk scene. Instead of performing in rock bars, which were located far from their usual hangouts, Beijing punks had the opportunity to find new venues in the university neighborhood, Wudaokou, where young people used to hang out and buy cheap dakou CDs and tapes on street stalls.

Scream Club opened its doors around 1998, started by by Lü Bo, an artist from Shandong province. It closed down in 1999, and was soon replaced by other Wudaokou bars, such as Happy Paradise (开心乐园). During its very short life, Scream had an enormous impact on the Beijing punk community.

Punks found it the perfect place to hang out, drink, fight and perform. Among all the bands playing at Scream Club, four of them made history: Brain Failure, 69, Anarchy Boys, and Reflector, who were later grouped under the name Boredom Army (“Wuliao Jundui,” 无聊军队, also known as the “Boredom Contingent”). This name was bequeathed on the group of bands by Tina, an Italian foreign student and singer of the punk band Rockstar, who was surprised to hear Brain Failure’s singer Xiao Rong say that he was “bored” every day. To understand the importance of Scream Club for these bands, one has only to hear the song “Scream” (嚎叫) by Reflector:

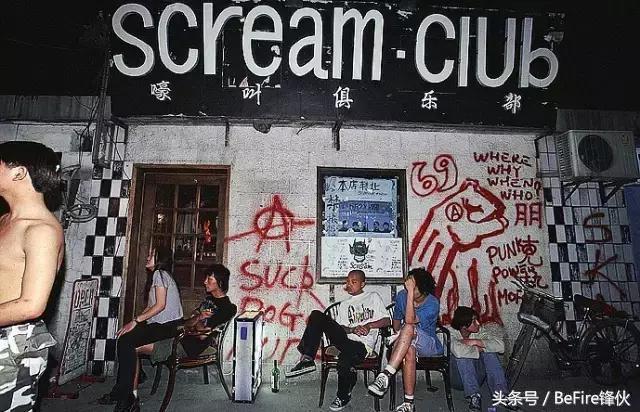

Chilling in front of the Scream Club in Wudaokou (photo by BeFire)

Chilling in front of the Scream Club in Wudaokou (photo by BeFire)

Scream Club was more than a live venue — despite its short lifespan, it transformed into a record label, Scream Records, which published the first punk compilation of the Boredom Army in 1999, as well as a live album of their 1998 Christmas show, Christmas in Scream! These are two very important records, which continue to influence punk bands in China today.

Scream Records did not only publish punk bands; they also signed the first nu-metal bands from China, like Miserable Faith and Twisted Machine, along with early hip hop bands CMCB and Yin Ts’ang. The record label itself was linked to the rock circle of the 1980s, since it was managed by Wang Di, one of the first rock musicians to play with Bu Dao Weng. In 2007, Wang Di paid a vibrant homage to the 1990s punk scene of Wudaokou with the song “Wudaokou 1998”:

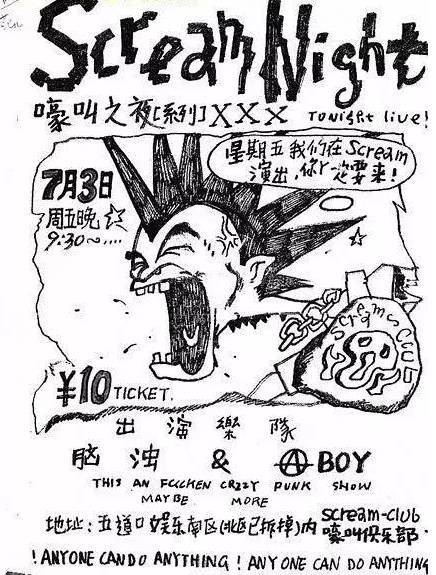

Poster of a concert at Scream Club with Brain Failure and Anarchy Boys

This partial and brief history of the early Beijing punk bands cannot cover the entire story of Chinese punk. It focuses solely on Beijing, but punk appeared at the same time in other parts of China, and those stories tend to be forgotten. Beijing punks often pride themselves as being the first punks in China, but this is contested by many — particularly Wuhan punks. But that’s a story for another time.

—

Cover illustration by Krish Raghav

You might also like:

Hang on the Box: The Illustrated Story of China’s Female Punk PioneersThe story of self-described “bitch-punk” band HotB, who were determined to break through the Beijing cultural underground’s glass ceiling in the late ’90sArticle Sep 04, 2019

Hang on the Box: The Illustrated Story of China’s Female Punk PioneersThe story of self-described “bitch-punk” band HotB, who were determined to break through the Beijing cultural underground’s glass ceiling in the late ’90sArticle Sep 04, 2019

WATCH: Stories Behind Dakou, China’s Semi-Illegal ’90s Music ImportsArticle Nov 15, 2017

WATCH: Stories Behind Dakou, China’s Semi-Illegal ’90s Music ImportsArticle Nov 15, 2017

The History of Rap in China, Part 1: Early Roots and Iron Mics (1993-2009)No, it didn’t all start with The Rap of China — far from it. In Pt. 1 of a two-part series, Fan Shuhong traces the history of hip hop in China from the 1990s to 2010Article Feb 01, 2019

The History of Rap in China, Part 1: Early Roots and Iron Mics (1993-2009)No, it didn’t all start with The Rap of China — far from it. In Pt. 1 of a two-part series, Fan Shuhong traces the history of hip hop in China from the 1990s to 2010Article Feb 01, 2019