When Sneaker Con launched in China this year — ten years after the sneaker expo was first founded in New York City — their audience was more than ready. Close to 20,000 “sneakerheads” crammed into Shanghai’s West Bund Art Center in May with shoeboxes in tow, buying, selling, and trading prized sneakers like stocks.

With streetwear and athleisure are steadily on the rise in China, many are putting their money towards one prized fashion accessory in particular: the sneaker. Limited editions of the likes of Air Jordan, Revenge X Storm, Fear of God Military and the covetable Adidas Yeezy Boost are sold — and often resold — for thousands of dollars.

Today, the overall athletic footwear market in China amounts to 9.5 billion USD annually, and as the Asian market grows in size and spending power, Chinese millennials are set to constitute up to 69% of it by 2021.

But sneaker appreciation didn’t start in China, or with its 400 million millennials. “Sneakerhead” culture has its roots in 1970s and ’80s-era America, the “golden age” of the NBA and a time when hip hop music was on the rise. Rap group Run DMC landed a sponsorship deal after rapping about their favorite shoe in “My Adidas,” and when Nike’s first collaboration with rookie basketball player Michael Jordan hit shelves in 1985, it kicked off their decades-long dominance of the shoe industry.

That began to change in 2013 when, after a string of successful limited-edition shoe launches with Nike, rapper Kanye West left them for Adidas. His Yeezy Boost 750s proved an instant success for the brand, with stores selling out stock in minutes, prices quadrupling on resale sites, and Adidas ultimately threatening Nike’s global supremacy.

Yeezy Boost 350 sneakers bought on Chinese resale app Poizon (毒)

It’s not surprising, then, that sneakers are gaining momentum in China, where a mix of American hip hop, K-pop and Chinese underground rap influence has produced a unique, highly personalized, yet label-conscious culture that expresses itself through its dress code. The influence of social media, and reality shows such as Dunk of China and Rap of China — in which streetwear is featured front and center — have helped edge sneaker savviness into the mainstream.

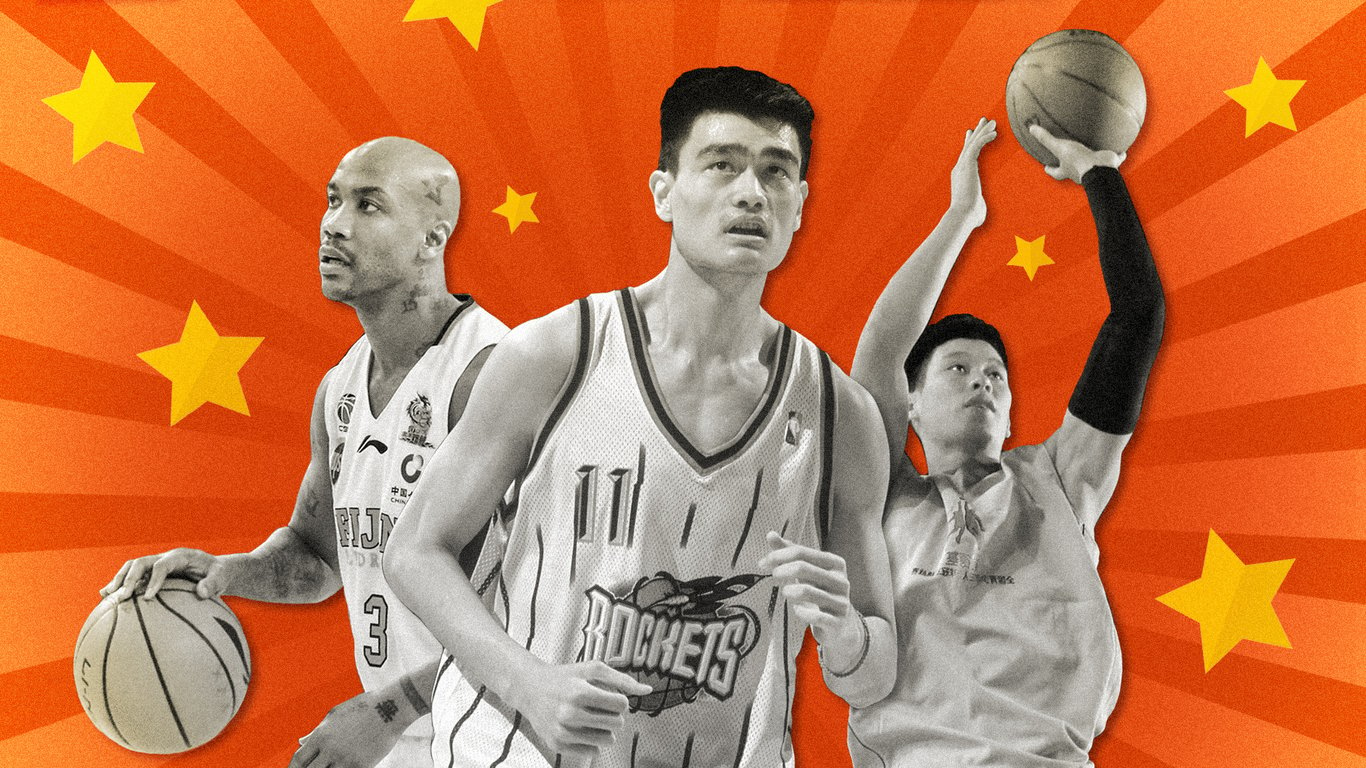

23-year-old Hector Hu, a student from Wuhan, bought his first pair of limited-edition sneakers when he was only eight. His favorite brand is Air Jordan, a love that was first kindled when his father took him to watch basketball games as a child, back in the days when Yao Ming first entered the NBA.

Related:

How Basketball Became China’s Most Beloved SportAnd no, it’s not just because of Yao MingArticle Aug 28, 2019

How Basketball Became China’s Most Beloved SportAnd no, it’s not just because of Yao MingArticle Aug 28, 2019

“During an All-Star Game, my dad pointed at someone and told me that it was [Michael] Jordan — the ‘god of basketball,’” he recalls. “From then on, I was a Jordan fan. I watched his videos, started playing basketball, and then began to collect sneakers. I don’t just collect Air Jordans, though — I collect all the shoes of all the stars I like.”

Sneaker Con co-founder Alan Vinogradov told RADII that celebrity collaborations — like K-pop star G-Dragon’s daisy-emblazoned Air Force 1 shoes, which were trending on Chinese social media platform Weibo well before their official release — as well as social media have helped expand sneaker culture to include a much larger audience in China. He also points to the “luxury sector, which is increasingly crossing over into streetwear,” as a key factor.

The Nike Air Force 1 x G-Dragon “Para-noise” sneaker (image: Nike)

Some young enthusiasts, like Hu, have become resourceful entrepreneurs, building solid side, or even full-time businesses out of the resale market and flipping rare shoes for as much as 60 times their retail value. In the case of black patent leather Solefly x Air Jordans for example, prices currently peak at 75,999RMB (10,730USD) on domestic resale app Nice.

To date, apps such as Nice, Poizon and DoNew together have more than 10 million monthly active users, and make up a market worth around 15 billion RMB (2.1 billion USD). Poizon (毒) alone is valued at three times that of US app StockX.

Fakes Make News

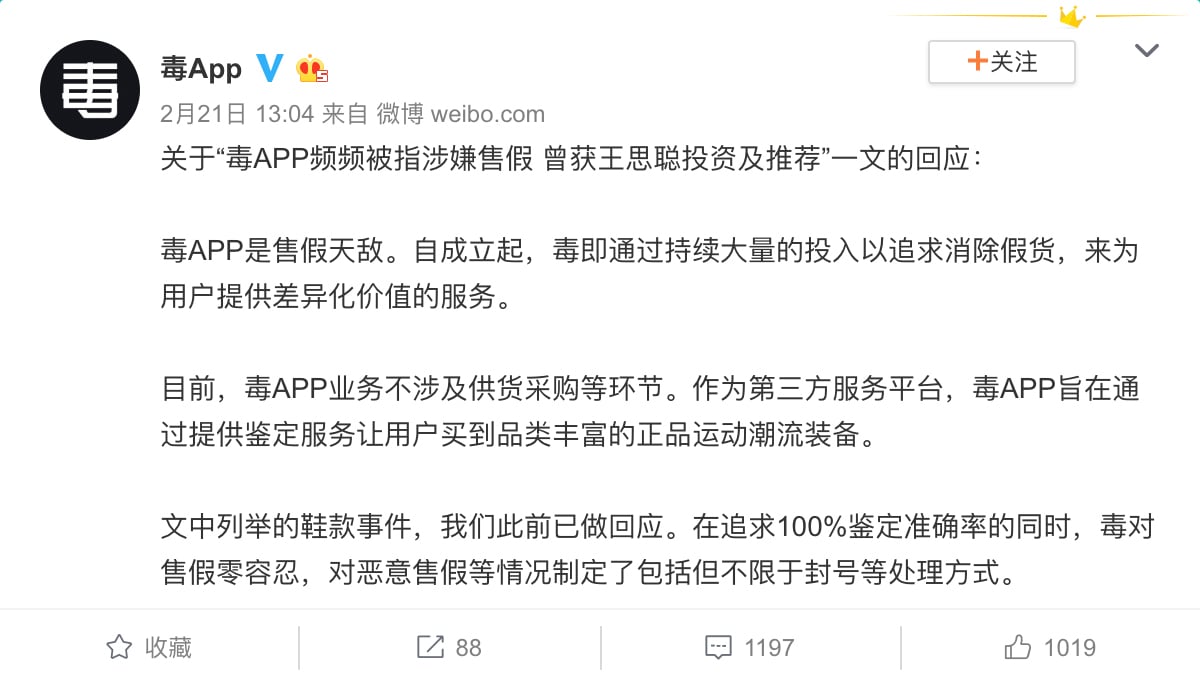

In February 2019, a customer claimed that a pair of sneakers that he acquired on Poizon were fake, and when he reported them, accused the app of trying to pay him 50USD as “hush money” (link in Chinese). Several other customers voiced their own accusations, and soon after the hashtag “#Poizonsellingfakesneakers” (#毒app疑疑售假#) amassed over 160 million reads on microblogging platform Weibo.

Poizon addressed the controversy on their official Weibo account, saying that while the platform does not get involved with suppliers, they were “pursuing a 100% identification accuracy rate” of goods sold on the platform.

Image: Weibo

This is of course much easier said than done. As the market for high-end sneakers balloons, the black market has surged to meet it, producing sophisticated fakes that are capable of fooling anyone short of an expert.

Hu says he’s never bought fake shoes himself, but he’s read the news reports. That’s why he and other collectors have had to become experts in their own right; in order to ensure a purchase is real, he looks for telltale signs of a shoe’s authenticity, from the fabric and detailing, to the lacing, glue drying pattern, and even the smell. “Pirated shoes are generally quite pungent,” he remarks, “and most limited edition shoes have very small details that pirated versions rarely imitate.” And since Air Jordans are his favorite shoe brand, he especially knows his AJs inside and out.

Footwear is consistently “one of the top targets for fakes” worldwide, according to Footwear News, and since the secondary market has pushed prices for some sneakers to excruciating heights, it’s also alienated sneakerheads who “don’t have the means — or desire — to pay Gucci prices.” While thousands of sneakerheads flock to Hong Kong’s “Sneakers Street” (Fa Yuen Street) daily to track down a limited edition design, thousands more research the black market in Putian, China’s sneaker manufacturing capital, or order knockoffs and replicas from various websites.

This phenomenon is contributing to the rise of high-end counterfeits, which has created serious challenges for legitimate manufacturers, suppliers, and buyers. Enthusiasts and experts now have to test extensively to tell the real from the fake — which may explain why platforms like GOAT, and events like Sneaker Con, are gaining traction in China.

A Hunt for Authenticity

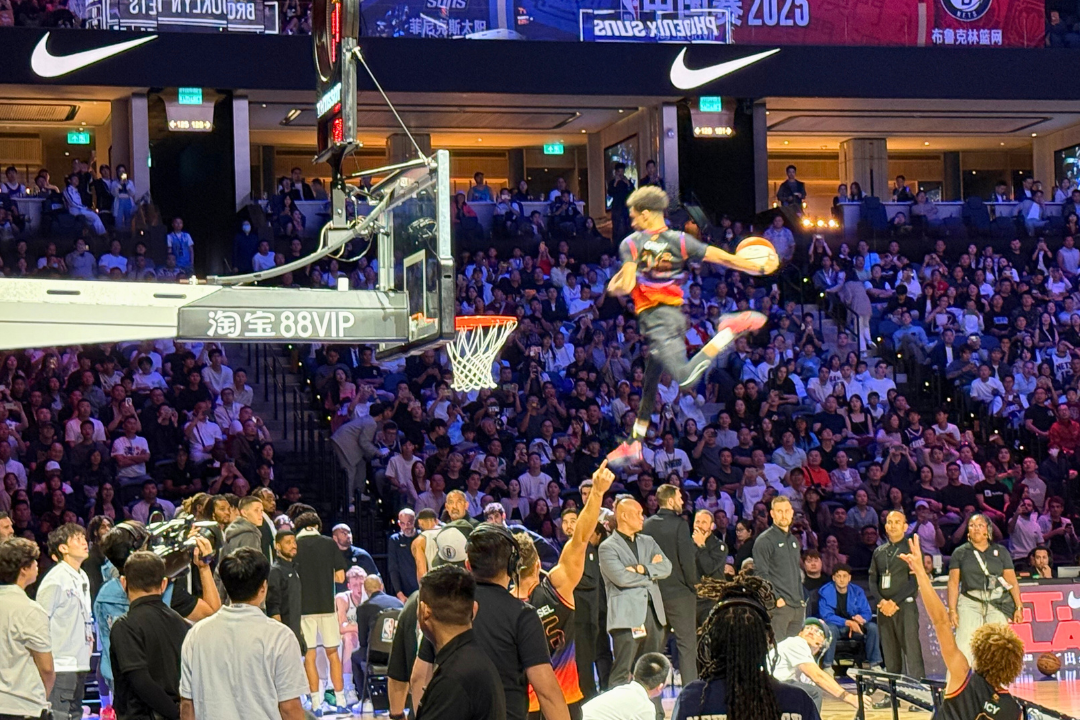

To commemorate the launch of GOAT’s China-specific app in August, the luxury resale platform spared no expense, flying out NBA stars like Houston Rockets’ PJ Tucker, and offering deals on some of their rarest sneakers at a three-day launch event in Shanghai.

GOAT launch in Shanghai (image: courtesy GOAT)

Henek Lo, co-GM of GOAT (short for “Greatest of All Time”), told RADII that although the localized app only entered the Chinese market a few months ago, their user base has already shown signs of “increasing 10 times year-over-year.”

Lo believes that a shift in values — which prompts events like the Poizon controversy, a backlash against counterfeits saturating the market — has pushed users onto platforms like theirs, looking to put their money towards guaranteed authenticity. “We find the growth in China is very aligned with the value proposition that our platform brings,” he says, “which is to source authentic sneakers globally for our customers in China.”

Indeed, the popularity of sell-out events like Sneaker Con shows that some Chinese youngsters will go to great lengths for a coveted pair of legitimate footwear. From unloading a month’s wages on prized kicks to losing hours queuing in front of stores and chasing online traders, Chinese shoe buffs will go to an awful lot of trouble for their dream shoe. Hu acknowledges that in their quest to collect, many sneaker lovers have strayed from the initial goal: to own and wear some of the most classic pairs, a slice of stardom and of history. “The shoe market is chaotic now,” he says, adding:

“Most people are out to make money — they don’t understand the background and culture of each pair of shoes.”

The world’s most desired sneakers to date are from international brands, such as Nike and Adidas, but Hu thinks that the market is beginning to change. One brand that he says is particularly popular among his sneaker collecting friends is Li-Ning, an athletic label founded by a former Olympic gymnast that has lifted itself from being seen as a Nike knock-off to gaining gravitas from shows at international fashion weeks.

Related:

Made in China 2.0: How Li-Ning Sneakers Went from Beijing Outlets to New York Fashion WeekArticle May 22, 2018

Made in China 2.0: How Li-Ning Sneakers Went from Beijing Outlets to New York Fashion WeekArticle May 22, 2018

As more people are looking for “made in China” fashion, domestic brands like Li-Ning have a “big advantage,” remarks Hu. “But if they want to gain the same respect as Nike has in China,” he adds pointedly, “they must make a breakthrough, not just follow the Nike line.”

Sneakers have come a long way from insipid shoes to highly-prized cult objects in the 21st century, and China’s sneaker-collecting community has flourished to encompass not only rappers and athletes, but also social media stars, celebrities, and knowledgeable cool kids who are willing to spend their last dime on limited-edition kicks. It’s a trend that shows no signs of slowing.

Header image: Limited-edition Air Jordans on display at GOAT’s Shanghai launch party (courtesy GOAT)