“There’s more than just production craftsmanship behind this record-breaking Chinese animation. There’s also a strong faith in the traditional Chinese culture and a creative way of expression.” These are the words that Chinese State news agency Xinhua used to describe the recent box office phenomenon, Ne Zha. “It has completely out-performed the big American production The Lion King, both in market and critical reception,” the report continued, hammering home the point.

As of 1PM Beijing time today (Friday August 2), the film had pulled in over 1.5 billion RMB (21.7 million USD) since its premiere on July 26, and this evening overtook Disney’s Zootopia and Pixar’s Coco to become the highest-grossing animated film ever shown in China.

Who is Nezha? According to Wikipedia, Nezha is ultimately based on two figures from Hindu mythology. Nezha has frequently appeared in Chinese mythology and ancient Chinese literature and the most commonly known Nezha story is one of those tales as old as time — any attempt to summarize it will be made at high risk of sounding absurd. So here we go: Nezha is a little boy who fought evil dragons and killed himself as a statement to his parents, then later was brought back to life by his deity mentor and was reborn from a lotus flower with three heads and six arms, eventually becoming a deity himself. This summer’s animated blockbuster is an adaptation from this story.

Invested and distributed by entertainment giant Enlight Pictures, Ne Zha took five years to complete production, with a crew of 1,600 animators. But those efforts appear to have paid off spectacularly. The rating for the film on Douban, a user review site known for its hard-to-please membership, is as high as 8.6 out of 10. Audience and media reviews are predominantly positive. And the film has been called “the glorious light of domestic anime”(国漫之光 guoman zhiguang) by netizens and media — though this is a term that emerges every time a domestic anime production hits screens, reflecting how the market is usually dominated by animation from the US or Japan.

Related:

The high production values of the film especially shine through in its elaborate action scenes. “I wasn’t expecting to see an animated Chinese film operating at this tech level — it’s really astonishing,” says Ruby, a 29-year-old Taiwanese 3D animator. “The animation is heavily influenced by gaming culture, from overall art direction to how the fighting scenes are done, but this is one of the reasons the Chinese animation industry has developed so fast.

“The gaming industry fed and cultivated animation talents, then they went into creative animation production.”

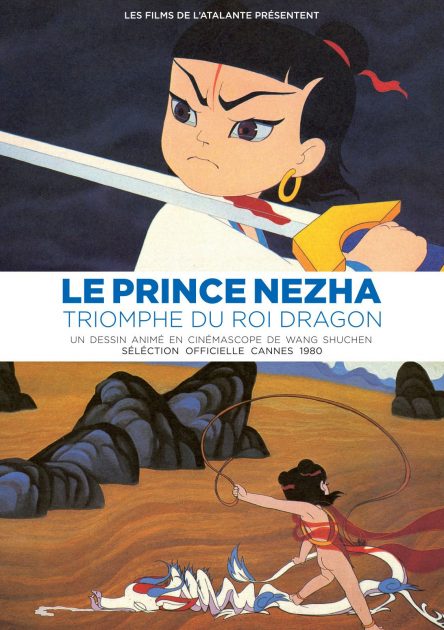

Another potential ingredient in the movie’s staggering success is nostalgia. This isn’t the first time Nezha’s story has been told on the big screen. Back in 1979, Shanghai Animation Film Studio produced Nezha Nao Hai, which placed the Nezha story in traditional Chinese aesthetics, both visually and musically. The film also kept the suicide plot from ancient literary work The Investiture of the Gods (封神演义 Fengshen Yanyi), where Nezha appears as a character, making it one of the most iconic scenes in the history of Chinese animation.

Watch Nezha Nao Hai below:

Shanghai-based, 23-year-old animator Zixingche is a huge fan of Nezha Nao Hai. “The scene where Nezha threw himself on a sword really left a mark on my childhood. The surrounding evil dragon kings, the common village folks who are suffering, Nezha’s father running towards him with a sword in his hand, the deer dashing through the lands trying to bring Nezha his ‘Universe Ring’ and ‘Red Armillary Sash’… The fast editing of these shots then led to a story climax — his heroic and resolute death.”

This powerful scene then took on its own life in pop culture, becoming a symbol of rebellion and refusing to compromise. Art-house master Tsai Mingliang directed Rebels of the Neon God in 1990, the Chinese name of which means “teenage Nezha”(青少年哪吒); Chinese old-school rock band Miserable Faith registered Nezha’s face as the band logo in 2006 and has incorporated it into two album covers.

“Personally speaking, the values that Nezha Nao Hai demonstrated, such as clear boundaries between good and evil, being independent and rebelling against the grown-up world, still heavily influence me today,” says Zixingche. “It prevents me from making big money.”

If you’re old enough to have seen both versions, you can’t help making comparisons and playing favorites. “The family members who are tough on you and refuse to communicate with you, they always end up loving you the most — I really can’t accept this tiring narrative,” says Philia, a 26-year-old motion graphics designer, adding:

“I prefer the ’79 story where he killed himself — that’s just so punk.”

C.Hi, a 25-year-old 3D animator, believes that “the new story is adapted for current values,” but finds it more compelling for exactly this reason. “It doesn’t follow the old version where the evil dragons are evil for no reason and they forever will be — the dragons in the new Nezha film are so much more complex and convincing characters. They’re more than the traditionally two-dimensional bad guys.”

A French poster for the 1979 version of Nezha, which featured in the official selection at Cannes in 1980

But unlike other recent Chinese box office smash hits, this may be one that doesn’t travel abroad (even if the 1979 version made it to Cannes’ official selection). The names and terms are almost impossible to translate without being confusing. Unlike a Disney or Pixar production where they see the Chinese market as an important overseas battlefield, Ne Zha hits a native local market of 1.4 billion people who inherently understand the complex mythology backstories and get all the meticulously-placed jokes without a language barrier.

That kind of care-free and yet well-executed entertainment is exciting for the audience and is bound to create more demand for films like Ne Zha in the future.