C-PUNK STORIES is a RADII column on the history of punk rock in the People’s Republic of China by University of Hong Kong postdoc Nathanel Amar.

In 2013, I was invited by an obscure French anarchist radio show to talk about the history of Chinese punk — they’d discovered the existence of punk in China thanks to Beijing band Demerit’s performance in Paris that same year. I was prepared to talk about the emergence of Chinese rock in the early 1980s, and the appearance of punk music in the mid-’90s, while drinking warm cans of beer with the radio hosts. But I was not prepared for what came next.

The host asked me if I knew about Dragons, the “first Chinese punk band,” who had released a record in France in 1982. I had never heard of them. He took the “Dragons” vinyl from his bag and played it on the show. The band was singing in Cantonese, and covered a song from the Sex Pistols (“Anarchy in the UK”) and another one from the Rolling Stones (“Get Off of My Cloud”).

Based on my research, I hadn’t thought a band like this was possible in the 1980s. In 1982, only a handful of rock bands existed in China, mainly in Beijing. Wan Li Ma Wang (万里马王), the first rock ‘n’ roll band in China, was formed in 1979 by students of the Beijing International Studies University, for example. Once I got home from the show, I tried to find more information about this band that I’d never heard of: Where did they come from? Who published their album? It took me nearly five years to untangle the whole story.

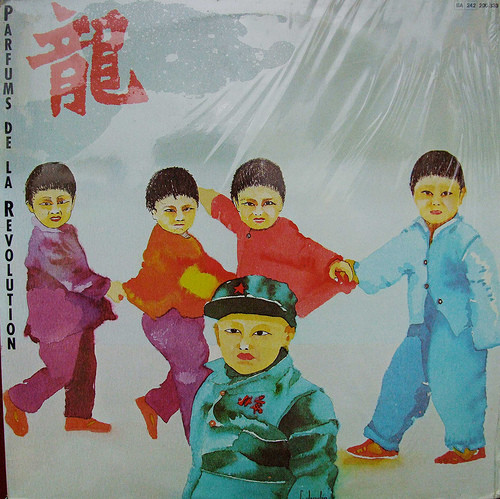

First, I found a copy of the record on eBay. The cover is a painting of four Chinese kids dancing behind another kid, who is dressed as a Red Guard with the characters “Beijing” (北京) stitched on his jacket. The band name is written in traditional Chinese (龍, long or “dragon”), and the album is titled in French Parfums de la Révolution (“Perfume of the Revolution”). Apart from the two covers, the nine original songs on the album have very cliché, Communist names such as “Red Torch,” “New China,” and “Dazhai,” a reference to a famous Maoist slogan. Another song on the album, “Ardent Flame,” is in fact a cover of a well-known Cantopop song, “Bei Cau Fong” (“悲秋風”). The whole album is sung in Cantonese, but the music was very similar to the French post-punk wave of the 1980s, besides the the presence of erhu (a two-stringed traditional Chinese instrument).

The only information available on the vinyl was the release year (1982), the last names of the musicians (Liu, Li and Kuo), the name of the composer (Zedletski), the producing label (Blitzkrieg Records), and the distributor, Barclay, a well-known French label. Not much to go on.

Fortunately for me, the French National Audiovisual Institute (INA) began at the same time to upload French TV show archives online. It didn’t take me too long to find what I was looking for: an interview with the producer of the Dragons album in 1982 on TF1, the first private French TV channel. In the two-and-a-half-minute interview, producer Marc Boulet, dressed as a Red Guard in front of the Eiffel Tower, states that Dragons is a punk band from Guangzhou who discovered rock and roll through Hong Kong radio and television.

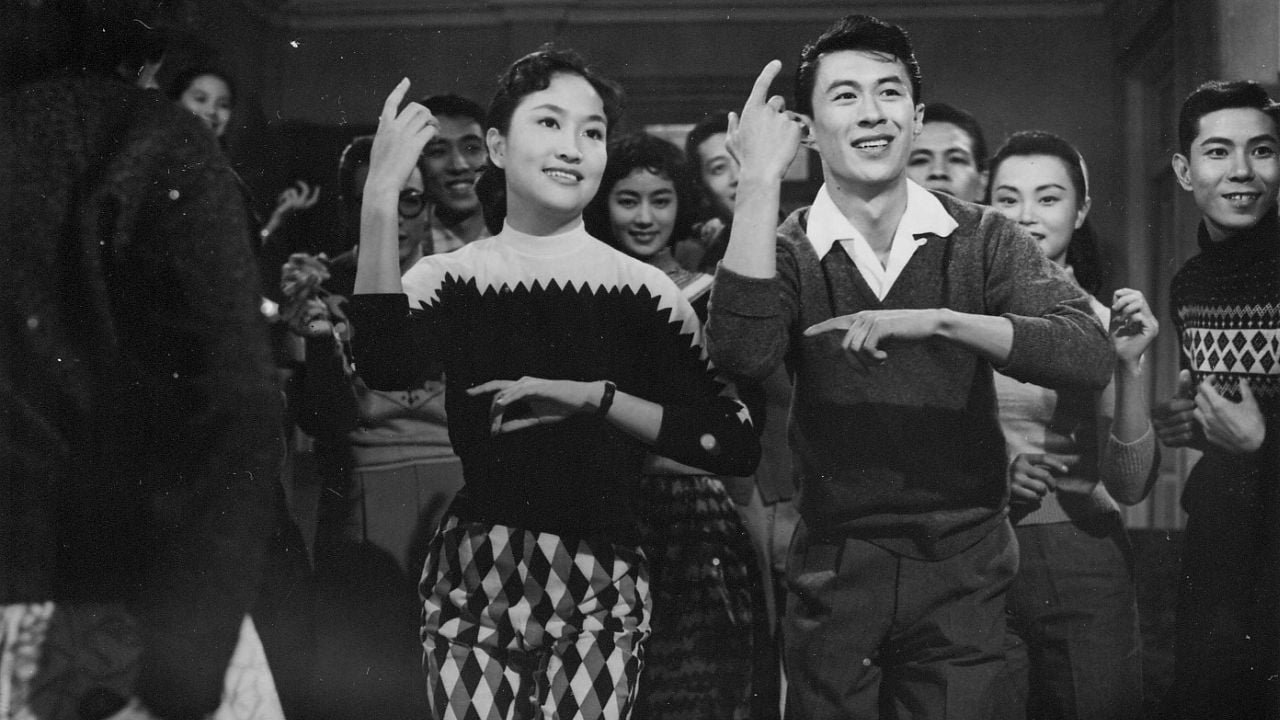

Boulet also talked about the political repression that the band has to face, with Western music being considered “decadent” and “not socialist.” It wouldn’t have been impossible for young people in Guangzhou to have been influenced by Hong Kong popular culture at the time — the historian Michel Bonnin in his book The Lost Generation shows that even during the Cultural Revolution, zhiqing (知青, sent-down youth) from Guangdong province were able to listen to songs from Hong Kong. But being able to form a punk band in the early 1980s and covering the Sex Pistols? That seems highly unlikely.

Marc Boulet is a very interesting character, a product of the post-May ’68 cultural turmoil and a disciple of a certain kind of gonzo journalism. In 1988, he published Dans la peau d’un Chinois (“In a Chinese Person’s Shoes”), where he claimed to have lived in China between 1981 and 1986 posing as a member of the Uyghur minority. He married a Chinese woman from Beijing, wrote a Chinese cookbook, and another book on his Chinese relatives ten years later.

He pulled the same trick in India in 1993, with Dans la peau d’un intouchable (In a Dalit’s Shoes), disguised as a dalit, the lowest caste in India. He also pretended to be a millionaire in Guangzhou, a forger in Taiwan, and a Stalinist in Albania. As he stated himself: “I don’t have the soul of a real trickster, cheating people is not for me an end in itself. If I put on a mask, it’s to discover the truth about societal problems.” As you might suspect, the general consensus among the French music circle is that Marc Boulet invented the “Dragons,” and somehow found Chinese singers in France to record the vinyl of the “first Chinese punk band.”

Unfortunately, I never succeeded in contacting Boulet himself, who now writes crime fiction set in China. But last year, a journalist from the French version of The Conversation, Aline Richard, who knew Boulet in the ’80s, told me her recollection of the Dragons story.

In the 1970s, Marc Boulet gravitated to the circle around the magazine Actuel, the most important French underground cultural journal of the ’70s and ’80s. At the same time, he was becoming interested in underground music from “exotic” countries. In 1979 he produced, through Blitzkrieg Records, an LP for Irish punk band The Outcasts. In 1981, he went to Poland — still a Soviet country at the time — and came back with an LP for early Polish punk band Kryzys.

Boulet wanted to repeat this process in China: finding a punk band in a Communist society to impress the French counter-cultural circle. When French composer Jean-Michel Jarre became the first foreign act authorized by Chinese authorities to tour the country in 1981, Boulet somehow managed to come along, hoping to scout underground Chinese bands to produce along the way.

Unfortunately, the audience seemed to show “more interest in the spectacular lasers than the eerily hypnotic music,” as the New York Times reported. Jarre later produced a documentary on his China tour, The Concerts in China, which shows the very official atmosphere of his concerts — not a very punk setting. Of course, Boulet didn’t find any punk bands in China — even rock and roll was still an underground niche at the time. He should have come 15 years later.

In an article published on Douban, a user called “My Vinyl Record Complex” (我的黑胶唱片情结) mentions several news articles written about The Dragons and Boulet in 1982. An article published on Billboard on February 27, 1982, for example, tells the story of The Dragons as invented by Marc Boulet, confirming that Boulet claims to have found the three punks in Guangzhou during Jarre’s concerts in China. One anecdote in particular is worth mentioning: to promote the album Perfumes of the Revolution, Boulet “plan[ed] to slip a perfume-impregnated card in the album sleeve. He obtained some cheap perfume from a French company, but the chemical reacted against the vinyl, badly damaging the batch of 300 records.” You can’t invent that.

That was the story of the first fake Chinese punk band. Stay tuned for the real version of the history of Chinese punk, which doesn’t involve French music producers, erhu, weird cover versions of the Rolling Stones or even Guangzhou.