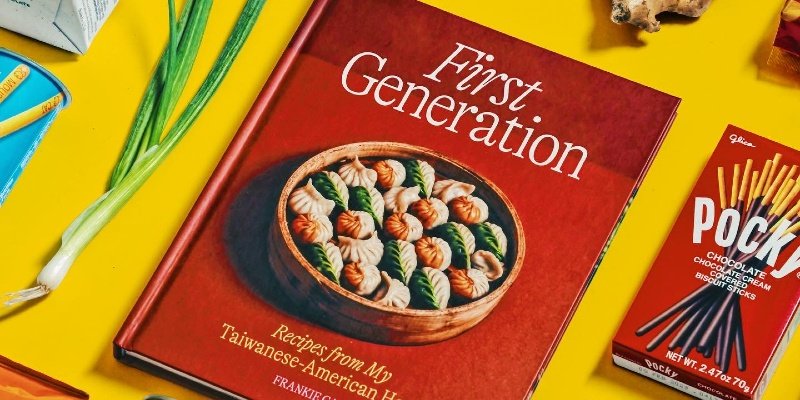

I did not expect to be bawling my eyes out reading a cookbook. A product designer turned food writer and photographer, Frankie Gaw published his debut cookbook, First Generation: Recipes from My Taiwanese-American Home, in October 2022. It is a cookbook with a lot of heart, celebrating immigrant heritage and identity.

Gaw grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio, and is now based in Seattle. His family immigrated from Taiwan in the 1980s. He wrote:

“I grew up culturally American but was never white enough to feel like I belonged. Yet within my own culture, I was so Americanized that my Taiwanese roots never completely felt like my own.”

It set the cultural authenticity threshold very high. This threshold for authenticity prevents immigrants or Third Culture Kid from feeling at home no matter where they are.

Gaw’s cooking philosophy and vulnerability provide a new path to belonging for those who struggle to find an identity off-the-rack. Forget the labels. Gaw stands right in the middle of the identity Venn diagram and embraces the intersection as the destination.

His efforts started with, simply, cooking more. Then came the food blog called Little Fat Boy, which led to more photography. As Gaw explores his writing and photographic style, the blog has amassed a following and won Saveur’s 2019 Blog of the Year.

He’s not afraid to mix and match, with dishes like stir-fried rice cakes with bolognese and Cincinnati chili with hand-pulled noodles. His recipes are welcome celebrations of all aspects of his first-generation immigrant identity.

“I just want it to feel like you’re eating in my grandma’s kitchen and getting the best kind of fat with 10-year-old plump me,” Gaw wrote on his blog.

In food media, Gaw saw beautiful spreads presented with Euro-centric aesthetics, whereas Asian food was often photographed and written up by non-Asian creators. This superficial presentation made the food appear foreign, even to Gaw, who straddles both cultures. He tells RADII:

“It became a motivation for me. I have the skill set to take photos like that, but I’ve never seen the homestyle, grandma food [that] Asian American immigrants see in their homes expressed in a way that’s celebrated in food media.”

Gaw adapted popular food media photography styles with an Asian motif. It’s not about ‘elevating’ Asian food, because that would be working from the assumption that Asian food somehow began lower on the totem pole.

“I want [the photographs] to stand out from what other food photographers were doing,” he says, referencing ’70s and ’80s Chinese cookbooks such as Fu Pei-mei’s. Gaw is determined to pay homage to his heritage with bold colors and classic styling.

In an opening essay for a chapter on small eats (小吃, xiaochi), Gaw recounts a circuitous conversation with his grandmother, who had Alzheimer’s.

The circuitous conversation is familiar to anyone whose loved ones endured the same cognitive decline. Gaw’s grandmother seemed to be time traveling and mistaking him for other family members. By the end of the story, Frankie and his grandmother finally connect and say, “I love you,” and I vowed to call my mother immediately.

Many of Gaw’s fondest childhood memories are associated with food or watching his family cook. Food served as a consistent love language, like words of affirmation and acts of service rolled into a bao.

Homestyle recipes are often freestyled, and Gaw himself describes his grandmothers’ cooking style as “cooking by feel.” But what if I don’t have a ‘feel’ for food? “Taste as you go!” Gaw encourages.

On his Instagram, Gaw shared a dumpling recipe where he used a hack passed down from his grandmother: Microwaving the stuffing to taste test without risking a botched batch or even a stomachache.

The book also features a belated coming-out letter to his father, who passed away eight years ago. This loss became the project’s catalyst and prompted Gaw to ask himself some hard questions about his life, a definition of success, heritage, and identity. “It threw me for a loop, this overwhelming life change and grief. It makes you ask, ‘Does it really matter?’ about a lot in your life. The loss helped me grow.”

He described the cookbook writing process as cathartic, “I had to write this book just for myself.” And since its launch, he’s connected with the broader Asian diaspora community and felt even more comfortable being himself.

Gaw’s First Generation serves as an inspiration for everyone in the diaspora community or anyone who has ever felt like they’re the odd one out. It’s proof that the center of your Venn diagram is where you belong.

All images via Little Fat Boy