China’s Digital Renaissance is a series exploring new currents in Chinese contemporary art, created in partnership with East West Bank. In this article, we speak with legendary artists Zhang Huan and Xu Bing about recent developments in AI art.

Venturing into certain corners of Instagram today means falling into a kaleidoscopic abyss of AI-generated art, with everything from zombie-like characters in dystopian worlds, to imaginary Art Nouveau-style wonders.

As a creative medium, generative AI is gradually eclipsing the NFT craze of the past few years, and has begun to make waves in the art world. AI has even made it to offline art fairs and competitions — last year, a Colorado artist made headlines when his AI-generated artwork won first prize, beating out the human competition.

Zhang Huan

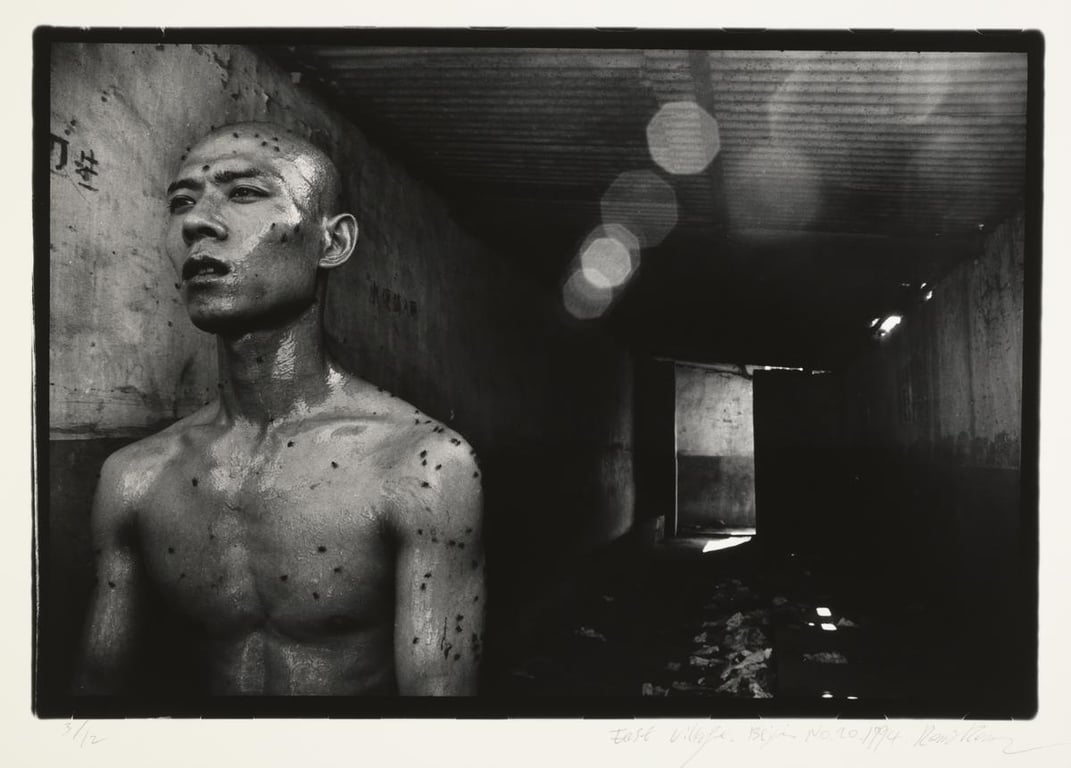

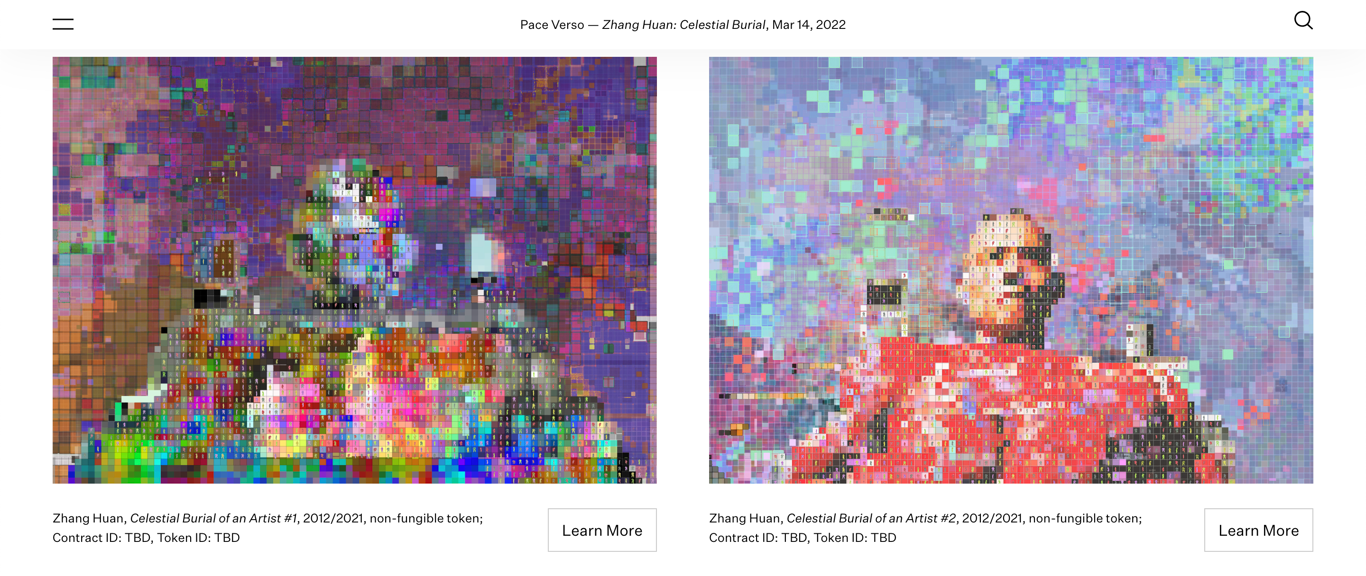

Rebellion and experimentation have always been at the core of Zhang’s work, but in the early days, he himself was the test subject. “In the ’80s in Beijing, I used my body to make art,” he says. “I was commenting on the political and social environment of the time.” His most daring performances involved self-inflicted punishments to shock his audiences and draw attention to the harsh living conditions of the poor in China. In his 1994 12m², Zhang sat still inside a filthy public toilet with his naked body covered in honey and fish oil. Swarms of flies feasted on him while he maintained a Zen-like demeanor. That same year, he pushed his limits even further with 65KG, in which Zhang was suspended from the ceiling by chains, once again naked, as blood was drained from his body. The performance lasted a whopping forty minutes. Zhang uses a broad spectrum of media, ranging from incense ash to steel, wood, and even cow skin, to create his paintings and sculptures, or as elements of his performance art. In 2002 he delivered yet another iconic performance, walking down Fifth Avenue and releasing white doves while wearing a suit fashioned from chunks of meat. (Mind you, this was eight years before Lady Gaga wore her meat dress to the MTV Video Music Awards.) The performance, titled My New York, drew inspiration from Tibetan sky burials, a funeral practice in which the bodies of the deceased are dismembered and offered to vultures. Buddhist philosophy and general history are recurring themes in Zhang’s work; recently he’s been researching ancient oracle bone inscriptions dating from the Shang Dynasty. Still, he’s no technophobe. “I’m someone who likes to experiment with brand new mediums and materials,” he says, before adding that he embraces emerging technologies, and is “particularly sensitive to the newest research.” In 2022 Zhang announced his first NFT project, a trilogy of works created in collaboration with Web3 platform EchoX. “When I started doing NFTs, I reflected: what should my first NFT be? Because I am a performance artist, I felt like I had to do something interactive,” he says. In The Celestial Burial of an Artist, the second piece in the trilogy, virtual interactivity meets ancient Buddhist rituals. The piece pays homage to My New York, replicating his iconic image in the meat suit with a digital avatar built from hundreds of pixelated, meat-suit-clad miniatures. Over two thousand participants customized these small pieces during an interactive, gamified art session. The game was like a digital version of the Tibetan burial tradition: players could choose to reclaim the sections that composed Zhang’s avatar, and mint them into NFTs — like vultures extracting parts from a dead body.

In a similar vein, Zhang is interested in the Metaverse, and the possibility of eternal existence in the digital realm. He’s been developing the concept of a digital graveyard where people can buy their very own virtual graves.

“I spent over two years researching and understanding this field, how to combine the real and virtual worlds,” he says. “This can only be achieved if the right technology is there to support it.”

As for the dangers of mixing technology and art, Zhang believes it’s really up to us to make the best of it.

“Technology entirely depends on how you use it. If you use it well, it pushes people in the right direction; if you don’t, then it hampers us,” he says.

Zhang doesn’t think AI can replace humans. He sees the technology for what it is: a combination of models that summarize what they’ve been shown in order to create new content that resembles the original source material.

“Right now AI can only imitate humans, it doesn’t innovate. It just takes all the historical data it can collect and expresses them. If AI can truly innovate, then I haven’t seen it happening yet,” he says. To him, at least for now, creativity seems to still belong solely to humans.

However, Zhang has some harsh criticism about the way things are going online, and about the quality of the creative output he sees on social media, especially in China.

“If you want to be known by the general public in China, then you have to be a viral sensation on Douyin [domestic TikTok] and get a lot of traffic and followers. Then a lot of people will know you, but what’s the goal?” he shrugs.

He thinks it’s pointless to be a crowd-pleaser, feeding netizens trivial and predictable content.

“I think we have to change the system. Instead of giving the audience exactly what they like, we have to lead them in a direction they don’t know,” Zhang says. Case in point: a short video explainer that highlights the bizarre nature of 12m² has recently gone viral on TikTok with an inflammatory title: “The most disgusting performance artwork ever.”

Zhang has always taken risks. The public wasn’t always sympathetic to his work, and even the art world saw him as an eccentric outsider at first. Still, his ethos was always about finding his own space to express himself in innovative ways, and that’s why his performances continue to shock almost thirty years later. After all, replicating something that was made before is the role of algorithms. To really stand out from machines, humans need to innovate.

“Every field has mediocre and outstanding people. If you are a designer and you make what is popular and everyone else is doing, then you are not a good designer,” he says.

“Great designers and great artists are supposed to make something new, something that has the ability to shape the present and the future, and influence other artists, scientists, and politicians,” he adds. “Only what passes the test of history is art.”

The game was like a digital version of the Tibetan burial tradition: players could choose to reclaim the sections that composed Zhang’s avatar, and mint them into NFTs — like vultures extracting parts from a dead body.

In a similar vein, Zhang is interested in the Metaverse, and the possibility of eternal existence in the digital realm. He’s been developing the concept of a digital graveyard where people can buy their very own virtual graves.

“I spent over two years researching and understanding this field, how to combine the real and virtual worlds,” he says. “This can only be achieved if the right technology is there to support it.”

As for the dangers of mixing technology and art, Zhang believes it’s really up to us to make the best of it.

“Technology entirely depends on how you use it. If you use it well, it pushes people in the right direction; if you don’t, then it hampers us,” he says.

Zhang doesn’t think AI can replace humans. He sees the technology for what it is: a combination of models that summarize what they’ve been shown in order to create new content that resembles the original source material.

“Right now AI can only imitate humans, it doesn’t innovate. It just takes all the historical data it can collect and expresses them. If AI can truly innovate, then I haven’t seen it happening yet,” he says. To him, at least for now, creativity seems to still belong solely to humans.

However, Zhang has some harsh criticism about the way things are going online, and about the quality of the creative output he sees on social media, especially in China.

“If you want to be known by the general public in China, then you have to be a viral sensation on Douyin [domestic TikTok] and get a lot of traffic and followers. Then a lot of people will know you, but what’s the goal?” he shrugs.

He thinks it’s pointless to be a crowd-pleaser, feeding netizens trivial and predictable content.

“I think we have to change the system. Instead of giving the audience exactly what they like, we have to lead them in a direction they don’t know,” Zhang says. Case in point: a short video explainer that highlights the bizarre nature of 12m² has recently gone viral on TikTok with an inflammatory title: “The most disgusting performance artwork ever.”

Zhang has always taken risks. The public wasn’t always sympathetic to his work, and even the art world saw him as an eccentric outsider at first. Still, his ethos was always about finding his own space to express himself in innovative ways, and that’s why his performances continue to shock almost thirty years later. After all, replicating something that was made before is the role of algorithms. To really stand out from machines, humans need to innovate.

“Every field has mediocre and outstanding people. If you are a designer and you make what is popular and everyone else is doing, then you are not a good designer,” he says.

“Great designers and great artists are supposed to make something new, something that has the ability to shape the present and the future, and influence other artists, scientists, and politicians,” he adds. “Only what passes the test of history is art.”

Xu Bing

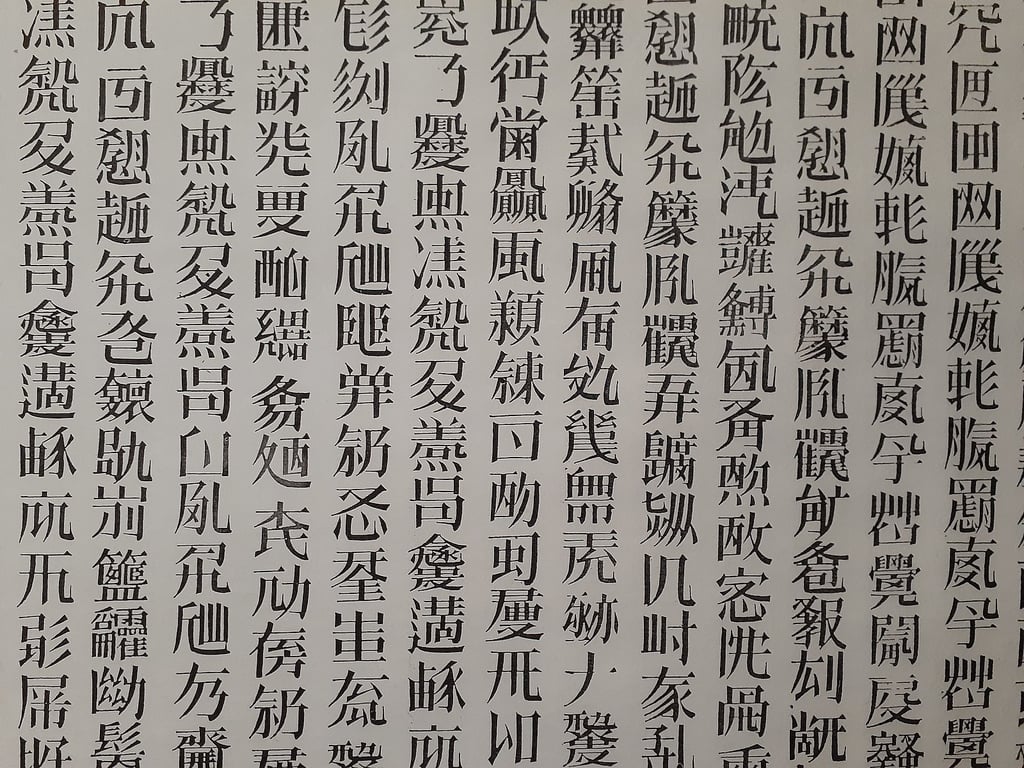

Just as Zhang intended to shock, Xu wanted to bewilder. He did so by meticulously subverting language, notably Chinese calligraphy. He presented it in disturbing ways, famously printing it on the bodies of copulating pigs. In part, his work reflects what he observed during the years of Mao, like the official simplification of Chinese characters in the late ’50s, and the appropriation of language for slogans and pieces of political ideology.