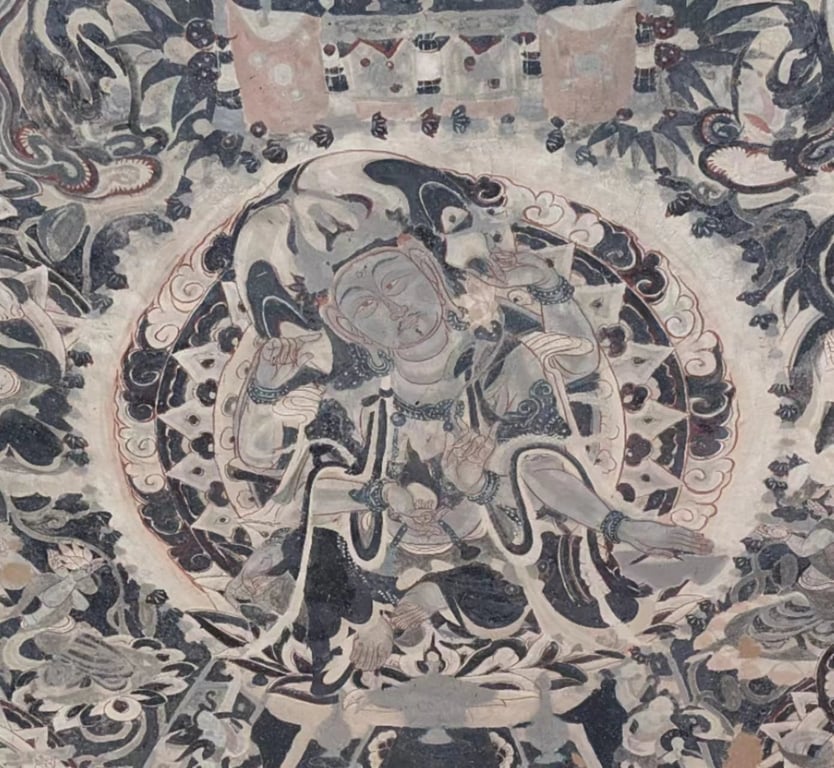

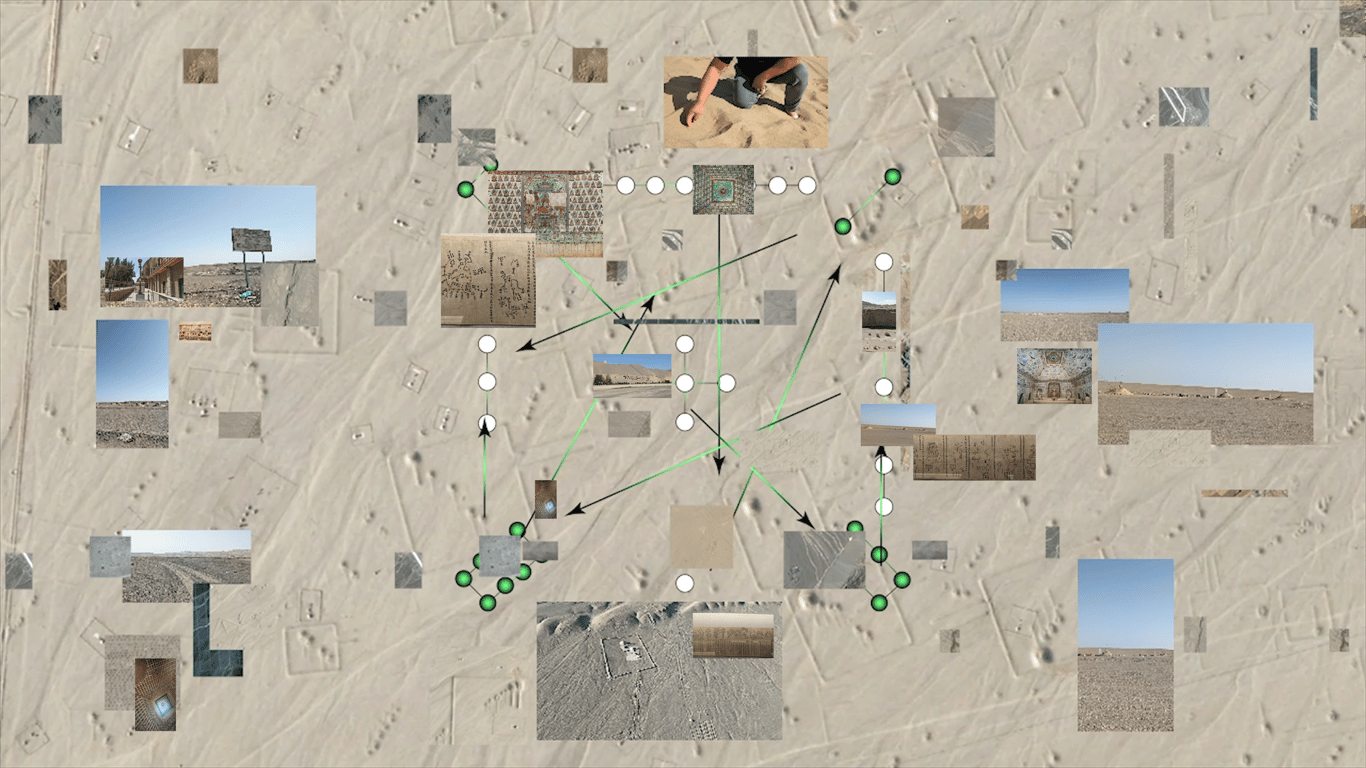

On the edge of the Taklamakan desert in the early 20th century, a Daoist monk paused his work on ancient Buddhist murals to light a cigarette. His smoke revealed a small, unnoticed gap in the wall. After digging through the sand, he uncovered a cache of manuscripts, spanning a millennium of Central Asian history in a dozen languages, some long lost like Songdian.

Among the 50,000 scrolls, a 7th-century star chart stood out as the first discovery of its kind — primarily because these types of celestial atlases were used by the Tang dynasty to steer significant political affairs, and the royal family treated them with the reverence and secrecy we now ascribe only to nuclear codes. Most importantly for everyday life, these astronomical maps were the main device used to plan agricultural seasons and prepare for droughts.

Today, Gansu faces a drought and environmental crisis that could only be grasped through the mysticism of a star prophecy. The region’s drying reservoirs, rising heat, and spreading desertification portend the future of many similar regions across the world, from the American Southwest to the Middle East’s Fertile Crescent. In recent years, Gansu has reemerged in international headlines with seasonal regularity, whenever spring sandstorms originating in the Gobi Desert sweep across Northern China and cover Beijing, Seoul, and Tokyo in sand.

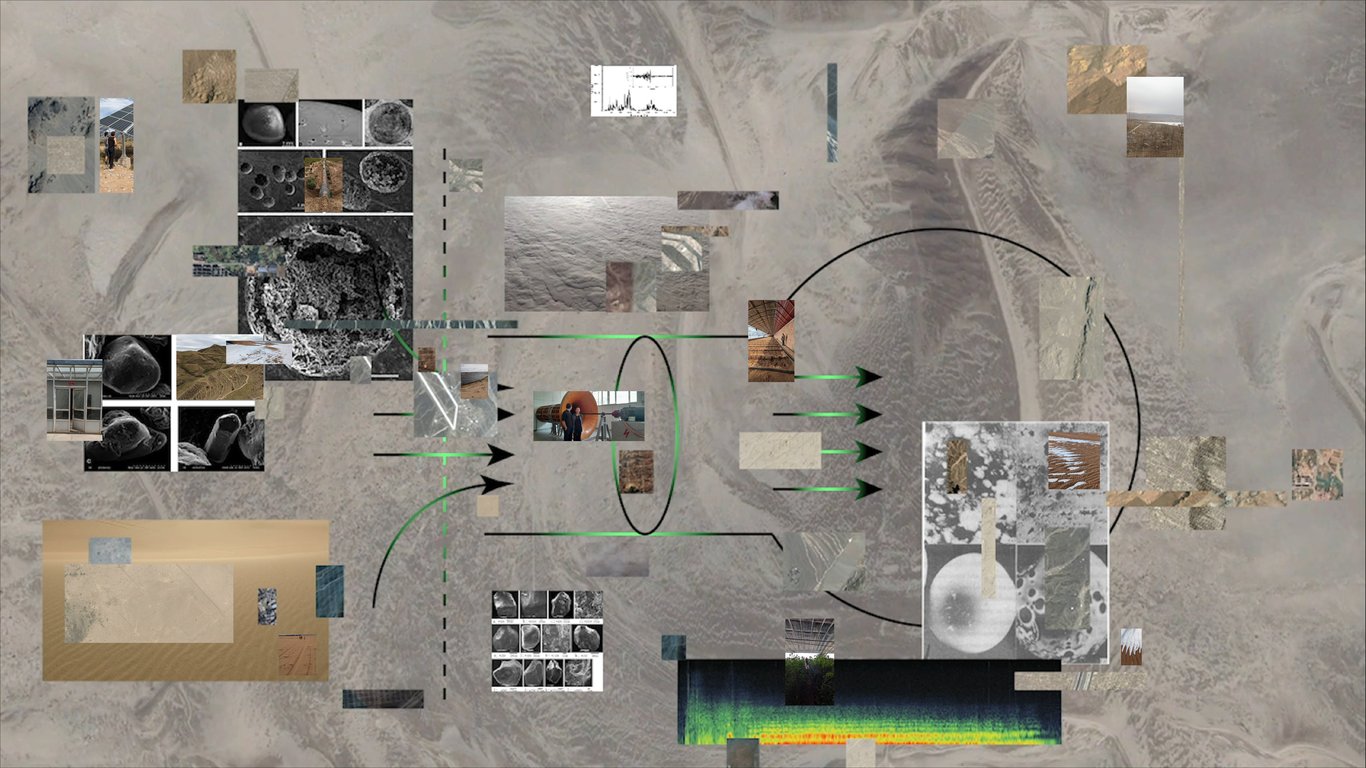

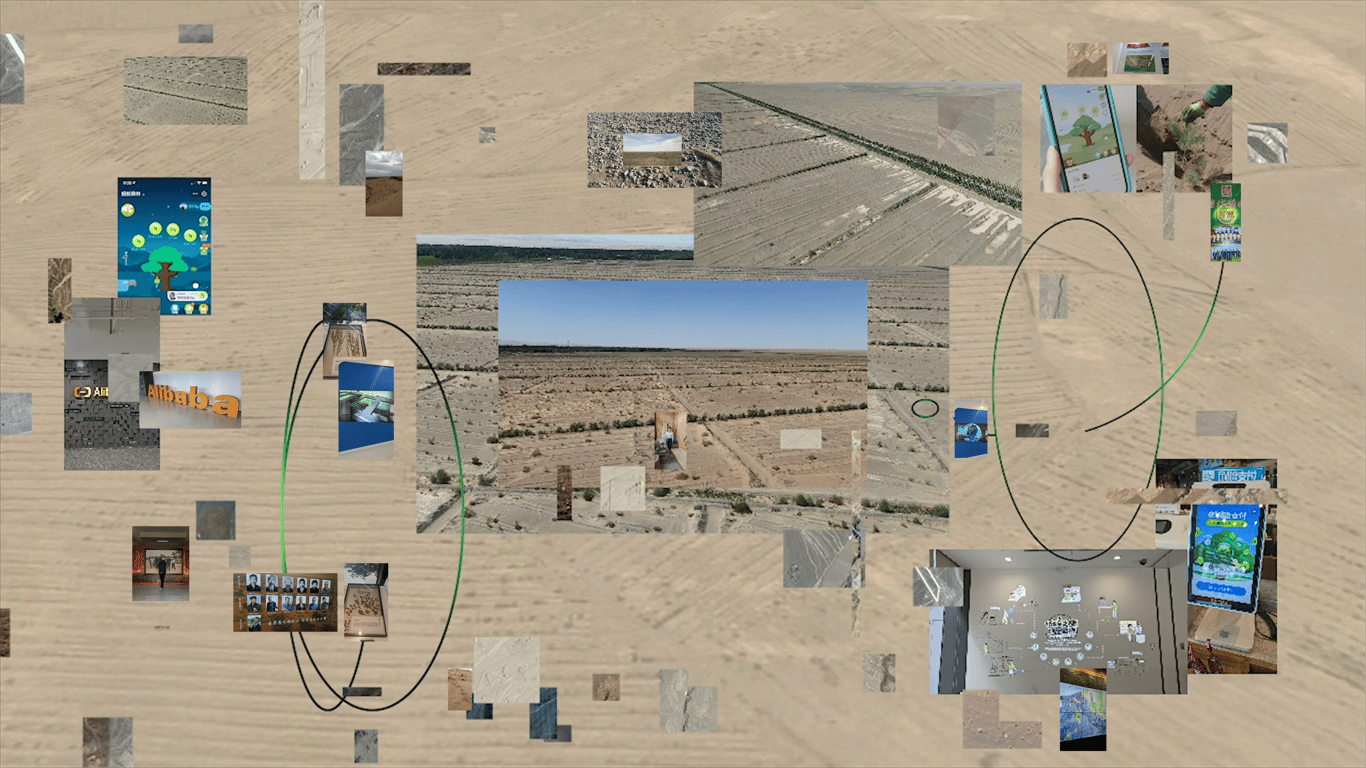

Flora Weil landed in Gansu 1500 years after the first star charts were written to investigate another, more geoengineered kind of planetary model. The designer/engineer/artist’s project Design in Rising Winds seeks to understand what new forms of design can emerge from a region that has been recomposed so meticulously by anti-desertification schemes and climate migration programs.

Weil has spent more than a year investigating the transformations taking place throughout Gansu on a grant from Hong Kong’s M+ museum — Asia’s biggest contemporary art institution — and Design Trust, an NGO established to support innovative design projects. When she arrived in Gansu in 2023, the province was in the midst of a pivotal year. First, the majority of its reservoirs had run dry and crops all across the province began to die. Second, the anti-sandstorm campaign designed to halt the desert’s growth reached a 40-year milestone for its artificially-planted trees quota. On paper, this initiative fully eradicated one of China’s major deserts, the Babusha.

When Weil and a coterie of environmental professionals embarked on a month-long trip through Gansu I joined them to try to understand what has made China’s deserts unique, and how the global response to environmental uncertainties are upending the domains of economics, technology, and design.

Gansu’s Planetary Emergence

In the global imagination, it might seem like Gansu stands on the periphery of world events. If judging only by GDP, this isolated desert province is one of China’s poorest regions. Its spectrum of exports mirrors the banal complexity of the global economy: integrated circuits, solar panels, coal, apples, and cement. Gansu’s Provincial Museum in Lanzhou luxuriously dedicates half a floor to the Longhai railway: the very first project of China’s original five-year plan and definitely not a destination point in your FTWeekend vacation guide.

But beneath the surface of historic marginalia lies the planet’s most ambitious climate adaptation project. For the last 40 years, China’s Ministry of Forestry has undertaken the “great green wall” initiative that has covered 70 million hectares of desertifying land with trees. Two deserts — the Kubuqi in Inner Mongolia and Babusha in Gansu — have been fully wiped off the face of the earth, ostensibly a success of mythological proportions. But the desert storms have continued. Some years are considerably worse than others, and none of the experts understand why.

Nonetheless, digital “great green wall” boosters have started to emerge. Over the last few years, Ant Forest has become China’s most popular reforestation app. Through Alipay, a billion and a half users can collect points for sustainable behavior, like taking the metro or foregoing disposable utensils for food delivery. These points can be spent on one of 20 different varieties of desert shrubs to be planted in rural Gansu. Alipay hires locals to go into the desert, plant, and monitor the user’s choice of sandstorm-fighting tree in a strange game of environmental Tamagotchi. Ant Forest has successfully gamified saving the planet, giving urbanites an emotionally convenient way to think about the climate.

We drove through hundreds of kilometers of dead sunflowers (one of the many fallen victims to the ongoing drought) in Central Gansu’s Wuwei, searching for an Ant Forest. None of the residents knew where it was, and there were no decipherable signs for it except a single glaring notice — an upbeat and marketing-approved description on the navigation app Gaode Map. Through sand dunes, abandoned homes, and a makeshift landfill stood a collection of forlorn shrubs. The ground was still covered in the plastic from the containers used to haul in the plants. We may have been unlucky, but this was an indicative sample of the growing digital sand economy.

During one of the 10-hour long drives through the psychedelically monotonous landscape, I asked Weil why she got interested in Gansu. A moment and another field of dead sunflowers later, she responded: “Hmm… I think I’m interested in things that hold contradictions. This world drew me in because it seemed to never quite hold still both in reality and in my imagination. It’s a place where scientific knowledge is unstable, where failure and success don’t really make sense.”

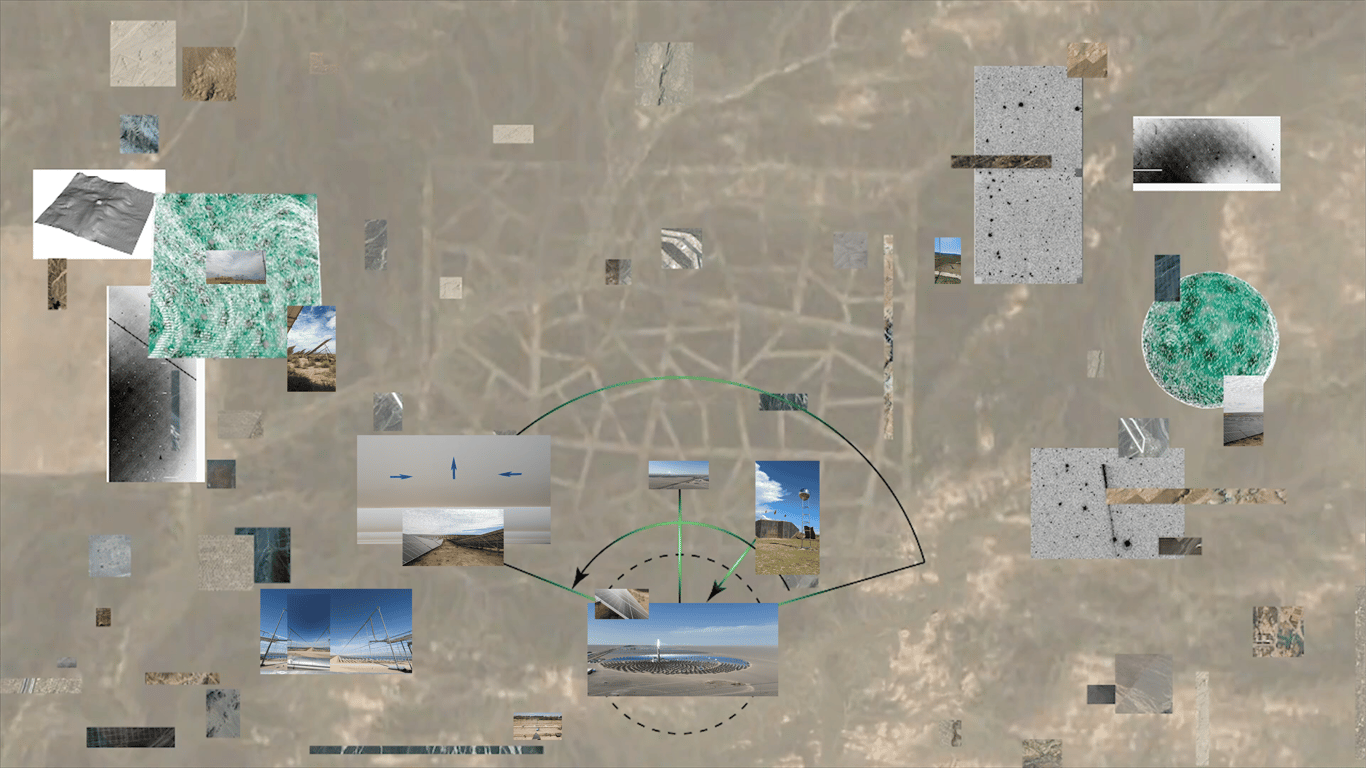

The majority of Gansu’s desert engineers are based at the Cold and Arid Regions Environmental & Engineering Research Institute (CAREERI) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The institute’s main laboratory in Lanzhou is home to the world’s largest man-made aeolian tunnel, designed to simulate wind patterns throughout the planet. The desert scientists (as they affectionately call themselves) are trying to figure out how the planet’s winds form, what causes sandstorms, and how to design storm-resistant infrastructure

During one of our meetings with CAREERI’s experts, Professor Xian Xue — head of the plant bacteria lab — cheekily asked Weil, “It seems like you are developing a whole new design principle, no?” The answer may be more extreme than she would expect: Gansu exemplifies the future of all modern design, spanning infrastructure, computation, and economics.

Flora Weil’s Path From System Design to Worldmaking

Flora Weil’s practice emerged from engineering and design, and now stretches to other, blurrier disciplinary spaces. Born and raised in Paris to Chinese immigrants, she studied at Smith College’s all-female engineering program, where she developed an interest in system design and thermodynamics. She then received a double Master’s in Innovation Design Engineering from the Royal College of Art and Imperial College, where she created a series of speculative machines for resource collection in a world defined by atmospheric optimization. For the final capstone, she designed an open-source alternative navigation device inspired by the polarized vision of insects.

As an artist, she first got exposed to the art world at Tomas Saraceno’s studio in Berlin, where she learned to design nature-technical interventions with spiders in the Arachnid Research Lab. Recently, she co-founded an interactive media studio and research platform called “Nephila,” named after a species of spider she used to breed. Through the studio, she produces experimental technology and design projects, the most recent of which is “Worlding as Research,”which focuses on prototyping open-source tools that turn world-making methods into forms of strategic research.

Yet Design in Rising Winds is Weil’s most ambitious project so far, weaving together her interest in the design and engineering of ecosystems with everyday life. She also revels in the uncertainty.

“Before I visited Gansu, I was reading Jerry Zee and Jesse Rodenbiker, learning about China’s ecological plans and the historical importance of the Hexi Corridor. I was already bewitched,” she reflects. “The people I got the chance to spend time with on site confirmed that what I was always most interested in was finding ways of being that co-exist with, and perhaps thrive from, the contradictory conditions of life.”

Weil’s project focuses on Gansu due to its global environmental implications, relocating the province from periphery to center stage. The sand blown from Gansu every spring not only covers the Beijing skies in apocalyptic orange, but even makes its way to Korea and Japan. The sands, while inherently local in origin, are transnational in their lack of boundaries, powered by the million-year-old geochemical rhythm that existed before the current manifestation of nations and will persist when they are long gone.

The Design of Control and Cybernetics

The fundamental logic of China’s techno-environmental paradigm — spanning digital services, economic incentives, urbanization schemes, wind tunnels, and sand fighting shrubs — can seem mundane to the modern observer. The main assumption being that the environment and social systems can be optimized though scientific and governmental intervention. But the way this assumption emerged and gets manifested is far from accidental, and is uniquely local.

At its partially visible base, Weil’s project is about exploring how state power is expressed through ecology in the extreme of the desert: from ancient irrigation works and Cold War missile testing to solar panels and afforestation. This logic is permeated by the work of 20th century systems scientists like Qian Xuesen and Norbert Wiener who established the field of complex systems modeling and control — cybernetics — that viewed society, environment, and economics through the lens of engineering. The planet became just a complex mathematical problem to be managed with the right set of levers. In this context, understanding the flight of Gansu’s sands is a window to the modern history of China’s technology and environmental governance.

From interest rate management to Covid infection forecasts, cybernetics is the modern logic of governance in every corner of the world. In Gansu, every poetic and tragic implication of this desperate attempt at control is laid bare. Weil’s Design in Rising Winds dissects the desert’s hidden lessons of all these inherent tradeoffs and complexities. It reveals how mechanistic forms of ecological governance don’t always produce mechanistic or controlled outcomes. Instead, there is a great deal of indeterminacy in the processes involved and those who live within this changing landscape navigate its limits with subversion and creativity. The project neither endorses nor admonishes, but takes the sand as it is: ever present, uncontrollable, and locked in an eternal dance with our borders, cities, phone apps, and legal structures. Ultimately, the sand is the final designer.

Banner image: Flora Weil, Design in Rising Winds: Research on Sonic Sand Dunes Produced by Microscopic Resonance Chambers, 2024. All images courtesy the artist.