What if there was more to see on the surface of the body than just skin?

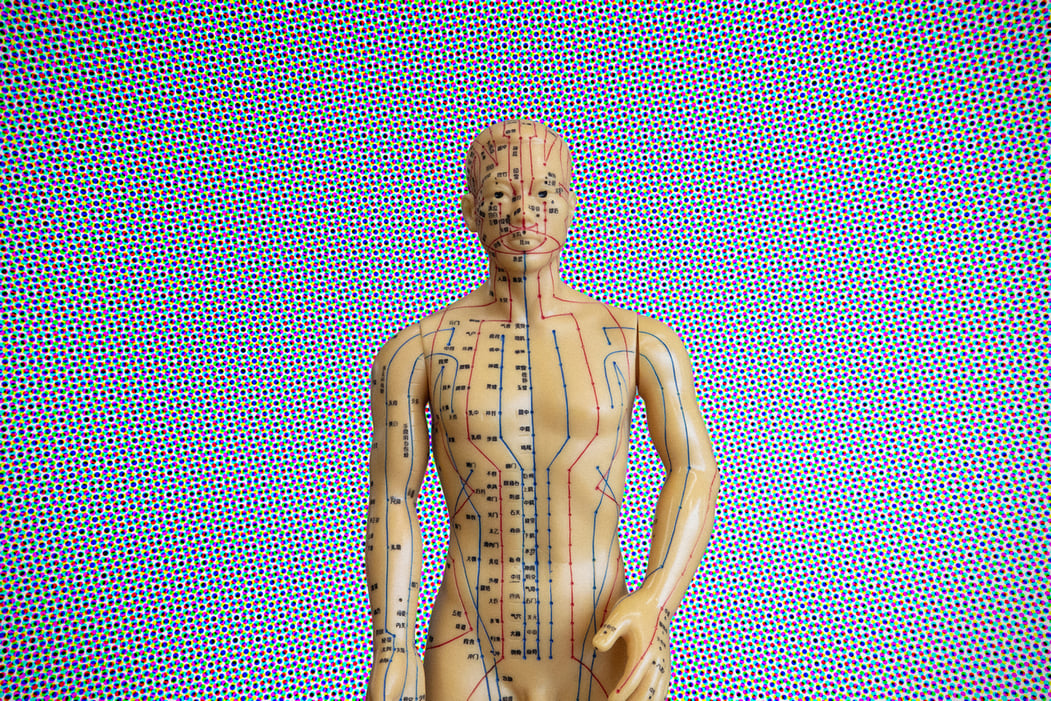

Enter the Bronze Man, a thousand-year old medical teaching tool. Unlike the anatomical models made of interlocking plastic organs you might encounter in biology class, the most important part of the Bronze Man isn’t hidden beneath his exterior.

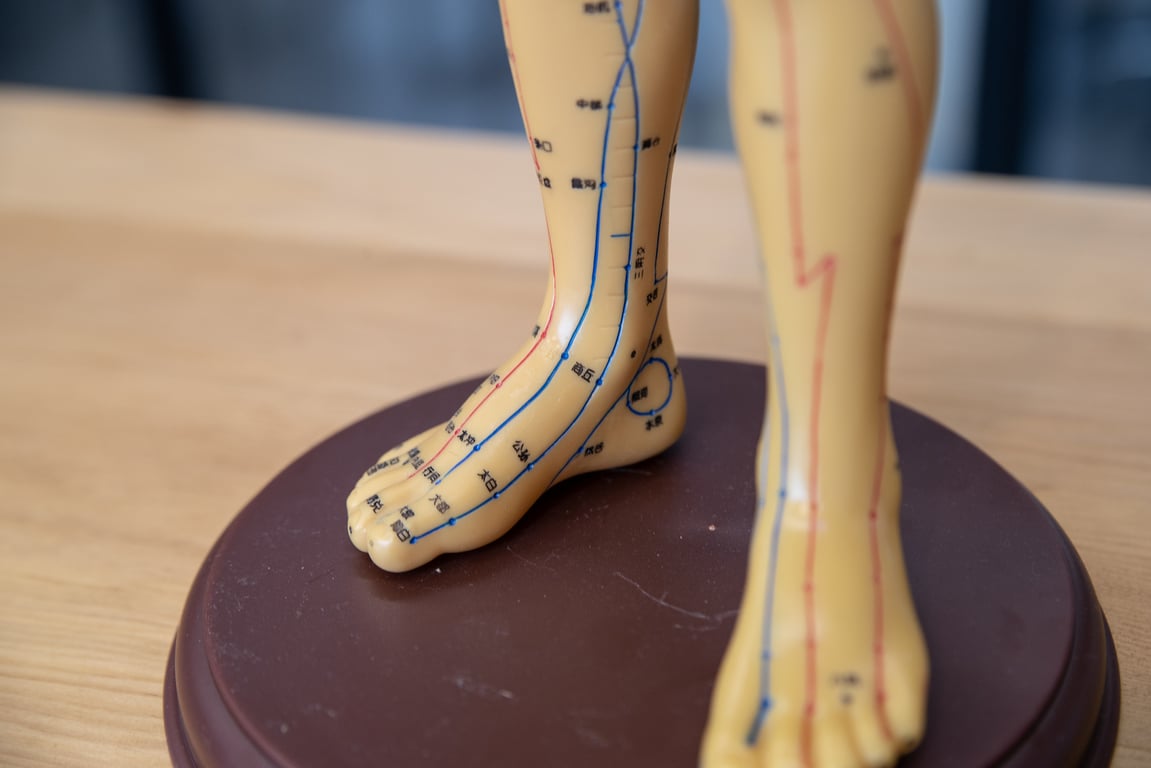

It’s the complicated map of intersecting channels called meridians (or jingluo, 经络) and points (often called “acupoints”) engraved on the surface.

While the jingluo channels may not readily integrate with the biomedical view of the body, in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) they provide a crucial network for understanding physiology and organizing treatment.

According to TCM theory, these channels traverse the entire body, from head to toe. They provide pathways along which qi and blood flow between the inner organs, muscles, and skin, interlinking body parts into a living system and creating unique opportunities for clinical treatment.

Chinese medicine physicians can insert needles, massage the flesh, or burn dried herbs (or moxa) at strategically chosen points along these channels in order to treat disease. This is where we get practices like acupuncture, acupressure, therapeutic massage and moxibustion, which act on the principles of these meridians.

Since each acupoint is a node within a wider network, the therapeutic effects of a single acupuncture needle, for instance, can extend throughout the whole body. Often this aims to improve the flow of qi and blood through a channel, or cause a dysfunctional inner organ that lies along that channel’s path to react.

Twelve channels form the central highways of the meridian system. Their names use the classical Chinese concepts of yin and yang to clarify the location and direction of their flow, as well as the organ system to which each corresponds.

Related:

Yin and Yang for Dummies: Dipping a Toe into the Theory of TCMArticle Jul 05, 2017

Yin and Yang for Dummies: Dipping a Toe into the Theory of TCMArticle Jul 05, 2017

For example, there’s a “Lung Channel of the Hand” and a “Liver Channel of the Foot” — we’ll explain the “hand” and “foot” part later.

Yin channels run on the insides of the limbs, while yang channels run on the outsides.

Each yin channel is linked to one of the five zang organ systems — the Heart, Liver, Spleen, Lung, and Kidney — the primary sites of physiological function.

Meanwhile each yang channel is connected to one of the six fu organ systems, which primarily participate in digestion and circulating fluids.

Physicians divide the yin and yang channels further into channels of the foot and of the hand, adding up to a total of four sets.

The three yin channels of the hand travel from the inner organs to the hand, where they intermingle with the three yang channels of the hand (which run from the hand to the head).

On the head and face, these channels flow together with the three yang channels of the foot, which run from the head to the foot. Finally, the three yin channels of the foot pick up at the feet and flow back into the abdomen. From a distance, with arms outstretched, the body might resemble a sort of bisected arrow shape, wrapped in meridians from top to trunk to toe.

The Bronze Man trained Imperial-era clinicians how to apply their knowledge of these flow patterns in clinical practice. By puncturing the Bronze Man with the correct series of needles, students of acupuncture could direct the flow of water through his body. Eventually, they’d call on the same skills to guide qi and blood through a living one.

The contrast between the Bronze Man and biomedical teaching models reflects broader differences between ways of thinking about the body. It’s hard to precisely locate acupoints within the biomedical body, and their complex circuits don’t necessarily correspond to the circulatory system or nervous system.

Some Chinese medicine physicians even claim that searching for these channels the anatomist’s way — through cadaver dissection — is doomed from the start: qi only flows through living bodies and dissipates at the moment of death.

Instead, for physicians and practitioners, confirmation of the channels’ existence lies in the effectiveness of the treatment methods that act upon them.

Related:

6 Acupressure Hacks Everyone Should KnowArticle Jan 08, 2019

6 Acupressure Hacks Everyone Should KnowArticle Jan 08, 2019