I place a small pyramid of herbs on Ms. Xu’s hand and light it with a stick of incense, carefully watching her face for signs of discomfort. “De le,” she says, “Enough.” I snatch away the burnt remains before they scald her palm. In total, three other students and I have burnt 300 of these moxa on exactly the same spot on Ms. Xu’s palm.

Ms. Xu suffers from trigger finger. When she curls her fourth finger, it initially refuses to bend back, before straightening with a faintly audible “pop.” The meaty area at the base of her finger is a bloodless white, and when I press it, she cries “Teng! Teng! It hurts! It hurts!”

Teng (“疼”) and its partner tong (“痛”) are a common refrain in the nephrology clinic where I work with chief physician Dr. Liu. Combined into tengtong, the two characters refer broadly to pain in terms like “chronic pain” (“慢性疼痛,” “manxing tengtong”). Individually, they attach to body parts to describe localized feelings of discomfort. Dr. Liu’s patients use these words to complain of headaches (“头疼,” “tou teng”) and painful urination (”尿痛,“ “niao tong”), as well as pains in the neck, stomach, legs, and eyes.

Just as often, “teng” and “tong” emerge as yelps when Dr. Liu and her students administer treatments of acupuncture, moxibustion, gua sha (刮痧 ) scraping, and ba guan (拔罐) cupping. One patient twitches and stiffens as Dr. Liu places each needle. Another cries out as the gua sha scraper travels down her back, leaving brilliant scarlet tracks in its wake. Afterwards, these patients leave claiming lasting relief from the pain that brought them to the clinic in the first place.

To people accustomed to meeting pain head-on by popping a painkiller, these pain-relief strategies might seem a little strange. Why do these methods of pain relief seem to hurt so much? And what can Chinese medicine tell us about how to deal with teng and tong?

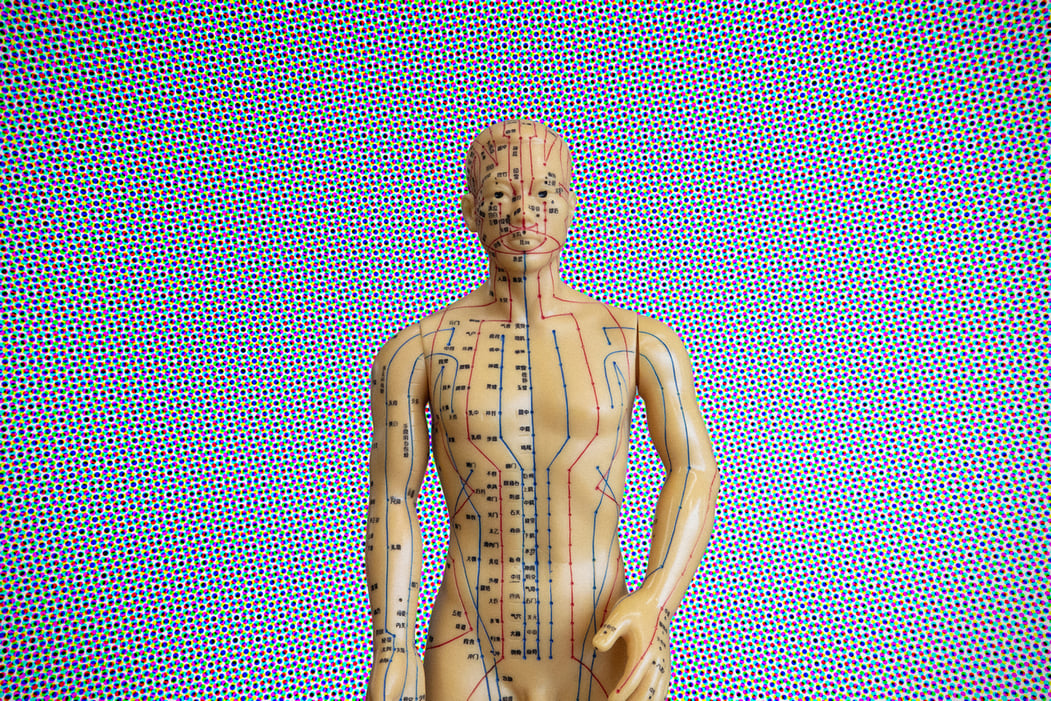

Dr. Liu explains that two principles establish the basis for Chinese medicine’s perspective on pain. The first principle is bu tong ze tong (“不通则痛”): when things do not flow smoothly, there is pain. Qi and blood flow constantly through meridians, channels that crisscross the body to coordinate physiological function and deliver energy and nourishment. When this flow is obstructed, we feel pain.

Related:

Changing the Channels: Breaking Down TCM’s Meridian SystemThe Bronze Man, a thousand-year-old teaching implement, helps us visualize some of TCM’s most important health practicesArticle Mar 05, 2019

Changing the Channels: Breaking Down TCM’s Meridian SystemThe Bronze Man, a thousand-year-old teaching implement, helps us visualize some of TCM’s most important health practicesArticle Mar 05, 2019

Dr. Liu uses her shoulder, which hurts during cold or windy weather, as an example. “Cold,” she tells me, “causes things to congeal.” Cold weather makes qi and blood turn slow and sluggish, building up into blockages that register as twinges and aches when she moves her shoulder.

Warmth and dampness can interrupt flow as well: think of overheated milk curdling, or the incremental ooze of fresh mud.

Related:

The Universal, Yet Uniquely Chinese, Experience of Being On FireIf you find yourself with “rising fire,” no need to stop, drop and rollArticle Jan 22, 2019

The Universal, Yet Uniquely Chinese, Experience of Being On FireIf you find yourself with “rising fire,” no need to stop, drop and rollArticle Jan 22, 2019

Second is bu rong ze tong (“不荣则痛”): when things do not flourish, there is pain. If there isn’t enough qi or blood to go around, then some body parts express their need for nourishment through pain. Since this pain comes from lack, it can be more elusive. Dr. Liu describes it as yin tong (“隐痛”), or hidden pain. The patient may not be able to point out a specific point that is painful, experiencing instead an ache that diffuses through the body.

Biomedical pain is a signal that travels lightning-quick across the nervous system, bouncing from neuron to neuron until it reaches the brain. Painkillers work by simply stopping the signal in its tracks — but don’t necessarily intervene upon pain’s underlying causes.

Meanwhile Chinese medicine’s two principles of pain suggest strategies for treating pain by reversing the pathological processes that cause it. If the movement of qi and blood through the channels is obstructed, then a physician’s first response should be to restore flow, whereas if the painful area lacks nourishment, then a physician must find a way to provide the vital nutrients it needs.

This isn’t necessarily easy, however, since methods like scraping and cupping come at the price of pain. As Dr. Liu explains to one patient, “The more blocked you are, the more it’s going to hurt.” The angry red and purple bruises that linger on patients’ backs and necks stand testament to this: they are the signatures that cold, warm, or damp qi leave behind as they depart the body, freeing the channels’ flow.

So why did we burn all those herbs on Ms. Xu’s hand? The white spot on her hand is a sign of cold, which has caused the tendons in her hand to stiffen and contract. The heat of the moxa will warm the tendons, making them supple, flexible, and lively with qi and blood. As the number of moxa we burn climbs, freeing obstructions and returning Ms. Xu’s hand to a state of balanced flow, Ms. Xu’s pain should gradually disappear.