It is easy to paint China as a villain in the global fight against climate change. The world’s most populous country is also the world’s highest greenhouse gas emitter, burning half the world’s coal supply each year. Our planet had a 0.6% increase in CO2 emissions in 2019; without China’s figures, it would have actually had a slight decrease from the year before.

Yet as a country China has also made strides towards sustainability. While the nation is still the world’s largest consumer of coal, it is simultaneously the world’s largest developer of renewable energy. And in response to the US withdrawal under President Donald Trump from the Paris Agreement — which aims to cap global carbon emissions — China expressed a renewed commitment to working towards climate solutions with other countries.

“Fighting climate change is a global consensus. It’s not invented by China,” said Premier Li Keqiang in 2017. “We realize that this is a global consensus agreement and that as a big developing nation, we should shoulder our international responsibility.”

So what exactly is China doing to protect its — and our — environment? And to what extent are these efforts having an impact?

Clearing the Air

China’s “airpocalypse” years are arguably responsible for putting the country’s leaders in the hot seat to more aggressively tackle climate change in the early 2010s.

In January 2013, cities such as Beijing and Shanghai were slammed with a month-long bout of smog, with pollution levels up to 30 times higher than what the World Health Organization deems safe. That same year, “abrupt environmental incidents” — an official term for protests — surged to 712 cases across the country.

According to a 2017 survey by the China Center for Climate Change Communication, air pollution was the climate risk that most worried people living in China. And for good reason — a study by the Chinese University of Hong Kong found that air pollution kills over 1.1 million people in China each year.

A key moment in climate dialogue came soon after: when China Central Television journalist Chai Jing produced Under the Dome in 2015, a documentary film that covered the extent of China’s air pollution and containment efforts. The film got over 150 million views in three days, and was even promoted by the government before getting censored.

But China’s central government had already begun to take action shortly after the 2013 “airpocalypses,” releasing the Air Pollution Action Plan in September that year. The plan identified the industrial sector as a prime culprit for pollution-causing emissions, and required major cities to reduce PM2.5 — a particulate matter and air pollutant — up to 33% by 2017. As pollution persisted, China then set a more aggressive Three-Year Action Plan, which mandated that by 2020, every city in China would reduce PM2.5 levels by at least 18% from 2015 levels.

The country has also developed more experimental ways of tackling air pollution. In 2018, the northern Chinese city of Xi’an built what was thought to be the world’s largest air purifier. The tower is over 100 meters tall, and produces over 10 million cubic meters of clean air per day.

Related:

![]() Photo of the Day: Xi’an’s Giant Air PurifierArticle Mar 20, 2018

Photo of the Day: Xi’an’s Giant Air PurifierArticle Mar 20, 2018

Beijing pledged to reduce its usage of coal — a leading cause of emissions — dramatically over the years to follow. However, environmental experts are worried now that some provinces have resumed building coal plants domestically in the interest of boosting infrastructure. What’s more, the central government has also continued to fund coal fuel projects overseas, making their anti-pollution stance seem contradictory.

Electric Slide

In China’s largest cities, transportation has become another massive contributor to air pollution. In recent years, China has released six sets of increasingly strict vehicle emissions standards, which have limited the cars allowed on the road.

The nation is also the largest buyer and producer of electric vehicles, accounting for half of global sales in 2018. But that number dropped the following year, when the government removed several subsidies and tax exemptions for buying electric vehicles.

Related:

Shenzhen Rolls Out Fleet of 16,000 Electric BusesArticle Dec 31, 2017

Shenzhen Rolls Out Fleet of 16,000 Electric BusesArticle Dec 31, 2017

China has seen more success with electric buses. In 2018, 421,000 of the world’s 425,000 electric buses could be found in China. (With every 1,000 e-buses, Bloomberg estimates that global demand for fuel drops 500 barrels each day.) The southern city of Shenzhen also set a worldwide first by becoming the first city to make all of its buses fully electric. Government subsidies were a huge reason for the shift, as electric buses cost two to four times more to produce than diesel ones.

Up until 2016, each e-bus in Shenzhen earned the city 150,000USD — more than half the bus’s upfront price. Bus operators also worked with those building infrastructure to install charging stations along most of the bus routes.

Related:

“Nobody Likes Waves of Trash”: China’s First Pro Surfer Turns Eco WarriorHainan-based Chinese surf star Darci Liu on her hopes to follow in Yao Ming’s environmentalist footsteps and to produce China’s “Blue Planet”Article Oct 25, 2018

“Nobody Likes Waves of Trash”: China’s First Pro Surfer Turns Eco WarriorHainan-based Chinese surf star Darci Liu on her hopes to follow in Yao Ming’s environmentalist footsteps and to produce China’s “Blue Planet”Article Oct 25, 2018

Waste Not, Want Not

Waste is an often-overlooked aspect of pollution, but it’s a problem China has been seriously struggling with. The country’s largest landfill site in Shaanxi province — with a capacity of over 34 million cubic meters — has filled up 25 years ahead of schedule.

After collecting 215 million tons of waste in 2017 alone, China took drastic measures by banning the import of plastic waste from other countries that same year. It created a crisis for countries dependent on exporting waste, such as the US, but was also a wake-up call around the world to cut down on plastic use.

China also upped efforts to manage its internal waste crisis. After select cities such as Shanghai implemented strict waste sorting rules to improve recycling, the country’s central government released a plan this year to ban single-use plastics. Among other things, the plan mandates that plastic bags will be banned from major cities in 2020, and from all other towns by 2022.

Related:

Wǒ Men Podcast: The Challenges of Going Zero Waste in ChinaCarrie Yu, co-founder of The Bulk House, talks about living a zero waste life in BeijingArticle May 31, 2019

Wǒ Men Podcast: The Challenges of Going Zero Waste in ChinaCarrie Yu, co-founder of The Bulk House, talks about living a zero waste life in BeijingArticle May 31, 2019

Ain’t Nothing but a Tree Thing

As China urbanized and industrialized at a dizzying speed — with an estimated 850 million people making it out of poverty since the 1970s — the environment took a tremendous hit. National forest cover dipped below 10%, and over 25% of the country had become desert by the late ‘90s. The 1997 Yellow River drought lost Shandong province an estimated 13.5 billion RMB, and in 1998, the Yangtze River had the country’s worst flood in half a century.

Shortly after came the country’s most recent sustainability movement. From 1998 to 2015, the country invested over 350 billion USD in sustainability programs mainly focused on ecological restoration. This included lowering erosion and flooding in rivers, reducing desertification, preserving forests, and increasing agricultural productivity.

In an effort to renew forest cover, China has been planting trees — lots of them. Grain for Green, a program launched in 1999 to reduce flooding and soil erosion in degraded farmland — would become one of the largest initiatives of its kind in China, reaching over 124 million people to date.

Today, 40% of China’s population is rural, and land degradation disproportionately affects the rural poor. Grain for Green pays farmers to plant trees on their land, and gives degraded land to rural families for restoration. And in 2018, China sent 60,000 soldiers out into its countryside to plant enough trees to cover about the size of Ireland. The program proved especially significant in that it highlights how poverty reduction remains at the forefront of China’s push for sustainability — or, that poverty reduction doesn’t need to come at the expense of the environment, like it has in the country’s past.

The Three-North Shelterbelt program is another similarly ambitious government program, started in 1978 and aiming for completion in 2050. The program will plant trees all the way along the 2,800km stretch of land facing the Gobi Desert, in an effort to keep the surrounding land from becoming more desert. It’s since become known as the “Green Great Wall” — as of 2017, 66 billion trees had been planted.

Related:

China’s Great Green Wall Against SandstormsSome lifelong Beijingers say sandstorms are as much part of the city as heavy rainfall is part of the tropics – but will it always be like this?Article Jun 16, 2017

China’s Great Green Wall Against SandstormsSome lifelong Beijingers say sandstorms are as much part of the city as heavy rainfall is part of the tropics – but will it always be like this?Article Jun 16, 2017

It hasn’t just been the government stepping in for more trees, either. Ant — the banking offshoot of tech giant Alibaba — released an app called Ant Forest in 2016. The app encourages users to record actions promoting a low carbon footprint, such as taking public transport or recycling. They receive points for each action, and with enough points, Ant plants a tree. As of last year, 500 million users had planted 122 million trees and reduced carbon emissions by an estimated 7.9 million tons according to data from Alibaba.

All in all, these efforts have seen results. Forest reserves have increased by 4.56 billion cubic meters from 2005 to 2018.

Building Resilience

Environmental restoration takes preventative measures against climate change, but preparing for it is just as important. Climate change brings with it extreme weather, from monsoons to droughts to heat waves. Urban development has caused flooding to more than double since 2008. How do we adapt?

Dr. Yu Kongjian, a renowned landscape architect and professor at Peking University, suggests “sponge cities” as a solution. Inspired by ancient Chinese farming strategies, his innovative methods aim to capture and reuse water while protecting against flooding. These cities use soft materials to absorb and reuse water for everything from irrigation to cleansing soil.

Related:

Photo of the Day: Sponge CitiesArticle Mar 24, 2018

Photo of the Day: Sponge CitiesArticle Mar 24, 2018

In 2015, China designated that 30 cities — including Shanghai, Beijing, and Wuhan — would incorporate the “sponge city” model into their urban planning. At least one-fifth of their land should include such features — such as grass swales or rain gardens — by the end of 2020. Other countries quickly took notice — the US, Russia, and Indonesia began looking into sponge cities in the years since.

Related:

Meet the Architect Whose Revolutionary “Sponge Cities” are Helping Combat Climate ChangeDr. Yu Kongjian and his “sponge city” model have helped change how we think of landscape architecture but also seen him branded a “US spy” by someArticle May 28, 2020

Meet the Architect Whose Revolutionary “Sponge Cities” are Helping Combat Climate ChangeDr. Yu Kongjian and his “sponge city” model have helped change how we think of landscape architecture but also seen him branded a “US spy” by someArticle May 28, 2020

Capping the Carbon

Right now, China is on track to reach its climate targets from the Paris Agreement. These include achieving 20% renewable energy out of all energy supply, reducing carbon intensity by 65% from 2005 levels, and peaking carbon emissions in 2030.

China announced plans for a national emissions trading system in 2017, creating a market for companies to buy and sell their carbon dioxide emission allowances. The system would also place an overall limit on each company’s emissions, incentivizing firms to produce less than their limit and sell instead.

Related:

Beijing Now Has the Cleanest Air Ever Recorded in the City’s HistoryBeijing might finally be catching a break from worldwide criticism of its airArticle Jul 19, 2019

Beijing Now Has the Cleanest Air Ever Recorded in the City’s HistoryBeijing might finally be catching a break from worldwide criticism of its airArticle Jul 19, 2019

Actual implementation has been continually delayed due to transparency concerns, though one official announced (hopefully) there would be a breakthrough by this year. If so, this would be a big move for China reducing its annual carbon emissions of around 12.3 billion tons. The system would be the world’s largest carbon market, a system that is already being used in places like California and the EU.

The priority of capping emissions has spawned a slew of innovative projects, in China as well as elsewhere. In Wyoming, a team from Suzhou, China is currently researching a carbon conversion project in which they’re trying to turn carbon emissions into plastics. “My solution is simple, and it’s one sentence: we will not allow any coal power station, natural gas power station, steel, concrete, or any industry with harmful pollutants and CO2 flue gas, to directly emit anything into the atmosphere,” Dr. Wayne Song, leader of the team, previously told RADII.

Related:

Meet the Scientist Who May Have Unexpectedly Solved China’s Smog ProblemArticle Jun 06, 2018

Meet the Scientist Who May Have Unexpectedly Solved China’s Smog ProblemArticle Jun 06, 2018

Bamboo cities are another idea that feels as futuristically sci-fi. The construction sector takes a serious toll on the environment, especially through creating materials such as steel and concrete. Penda is a Beijing- and Vienna-based architecture firm advocating for bamboo as an alternative. They — and entities such as INBAR (the International Network for Bamboo and Rattan) — argue that bamboo generates more oxygen than other plants, while still absorbing similar amounts of carbon dioxide, and is two to three times stronger than steel beams. Penda has described bamboo as a “locally sourced material with the lowest carbon footprint,” making it ideal for a rapidly growing city.

Related:

The Greener Grass: Can Bamboo Help China Build Sustainable Cities?In pockets of China’s construction scene, bamboo is considered “green gold” for its potential as a sustainable building materialArticle Jul 03, 2019

The Greener Grass: Can Bamboo Help China Build Sustainable Cities?In pockets of China’s construction scene, bamboo is considered “green gold” for its potential as a sustainable building materialArticle Jul 03, 2019

Renewable Energy

China has also set its sights on switching over to green energy. It currently has one of the highest investment rates in renewables abroad, and according to a report from the Geopolitics of Energy Transformation, it leads in production of solar panels, electric vehicles, and wind turbines, as well as renewable energy patents.

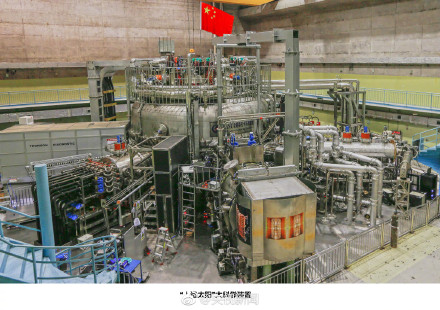

This investment also carries over to methods not yet in use. Last year in Sichuan, a team of scientists began testing an “artificial sun” for nuclear fusion research. Ultimately, the goal is to better understand how to generate clean energy — like our Sun does — and provide electricity to millions in China’s rural areas.

Related:

China has an “Artificial Sun” and it Just Hit 100 Million Degrees CelsiusArticle Nov 13, 2018

China has an “Artificial Sun” and it Just Hit 100 Million Degrees CelsiusArticle Nov 13, 2018

Indeed, green sources of energy such as solar power are already plentiful in both urban and rural areas. There’s so much solar power, in fact, that in hundreds of Chinese cities it’s currently cheaper than electricity. By 2024, China is projected to have the most solar panels in the world — over double the US’s. China is also home to the world’s largest solar plant in the world, located in the Tengger Desert, as well as many other mega-plants spread out across the country.

Some take a more cynical view of China’s international involvement in sustainability, however. Nobuo Tanaka, former executive director of the International Energy Agency, has said their efforts are frequently undercut by China’s geopolitical strategy.

In particular, concerns have emerged over the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a series of development projects stretching from Asia to Africa to Europe. Since the BRI was announced in 2013, 71 countries have joined. It’s been called a plot to leverage soft power, as well as a “debt trap,” where China gives countries loans they can’t repay.

China has pushed back against the accusations, and President Xi Jinping has voiced commitment to an environmentally friendly BRI. Chinese renewable energy company Chint Solar was among 11 other international firms to help construct Benban, a solar plant in Egypt so massive that it’s viewable from space. China Development Bank and China Export-Import Bank also helped front 85% of the costs to construct the largest solar plant in South America. Both were labeled as BRI initiatives. And in 2017, 30% of the solar energy plants China built were overseas.

Related:

Beijing’s Hanergy Launches Energy-Charging Umbrella, Donates First Batch to AfricaArticle Apr 28, 2018

Beijing’s Hanergy Launches Energy-Charging Umbrella, Donates First Batch to AfricaArticle Apr 28, 2018

We can expect more controversy and criticism as China continues to develop an international presence in sustainability. Yet at the very least, we can also recognize China as being serious in its efforts to combat climate change.