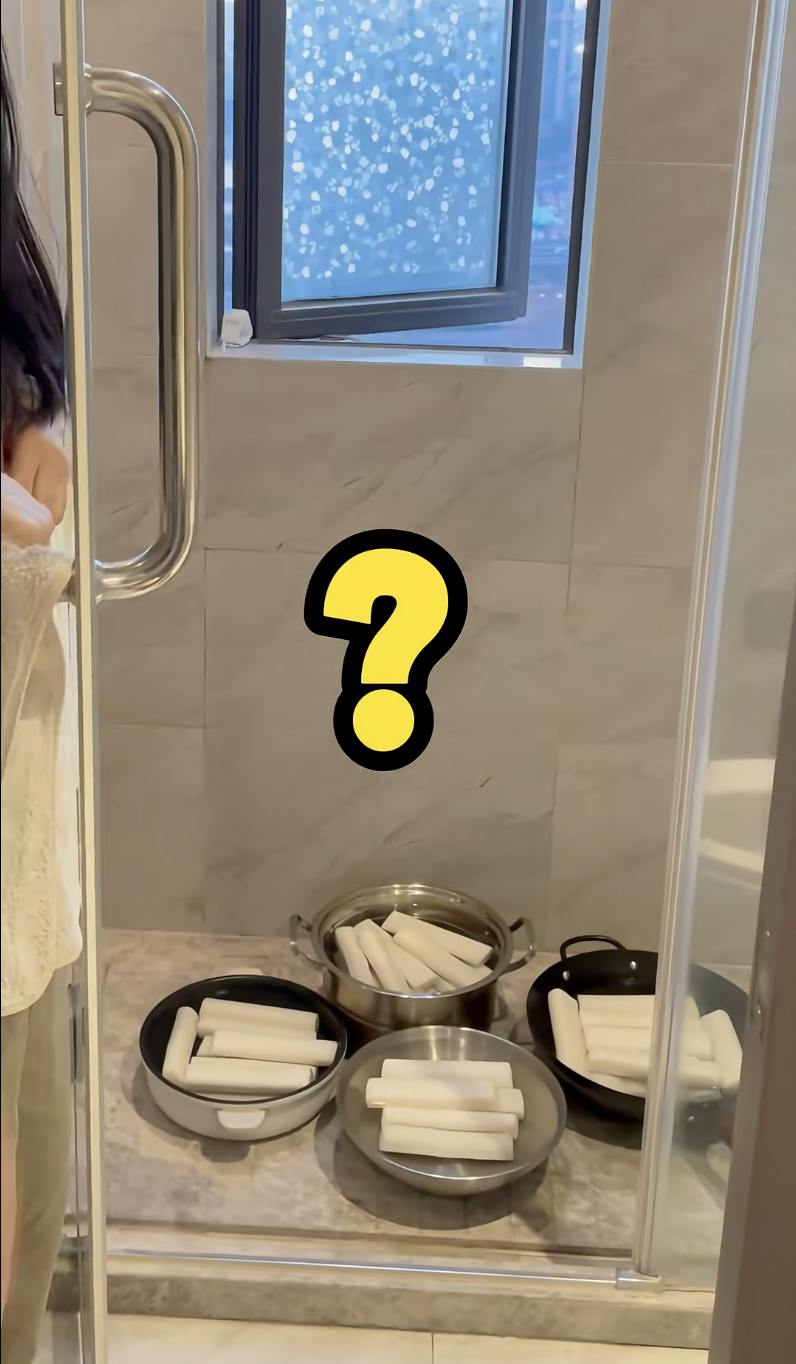

In parts of eastern China, especially Zhejiang, rice cakes are no longer waiting patiently to be sliced and fried. They’re being “raised.” The trend is called 养年糕 (raising nian gao), and yes, it involves treating slabs of glutinous rice cake like aquatic pets.

The setup looks oddly serious. Big ceramic vats. Clean water. A strict schedule. Every few days, the water gets changed to keep the rice cakes firm, fresh, and mold-free. Miss a swap and the texture turns mushy—an unforgivable outcome for something destined for Lunar New Year plates. Online, young people joke about being tied to home because their “rice cake” needs care, sharing tutorials and deadpan updates across Xiaohongshu.

It sounds ridiculous until it doesn’t. For Chinese Gen Z, 养年糕 scratches the same itch as pet ownership without the baggage. No vet bills. No landlords saying “no.” No emotional spiral when work runs late. Just a small, repeatable ritual that offers routine and a sense of responsibility—then quietly disappears once the holiday meal arrives.

Food-as-companion isn’t new either. During lockdowns, scallions in water jars became temporary green dependents. Mold from tea leaves was the new furry friend. But with rice cakes, they carry more cultural weight as they’re tied to prosperity and family, which gives the trend extra resonance.

Ultimately, this is about control and comfort in an exhausting era. Care, but make it light. Commitment, but with an exit plan. In today’s China, even a rice cake can double as emotional support—right up until it becomes dinner.

Cover image via Nano Banana Pro/RADII.