Editor’s note: This article by Rita Liao was originally published by TechNode. It has been re-posted here with permission.

“It’s probably the most popular live streaming platform in China at the moment, but also the most vulgar,” writes the user who started the provocative thread with screenshots showing Kwai users eating rats, dancing in skimpy clothes, and other behavior that might be straight-up insane or obscene for the cultivated urbanites. As of now, the question has more than 3.8 million views and over 1,000 replies.

Vulgar or not, Kwai has brought the focal point of city elites to the rarely discussed but colossal population living in China’s lower-tier cities and rural areas.

China’s tech giants have long seen the opportunities in lower-tier cities as the urban markets saturate and the geographic center of China’s middle class begins to shift. In March, Tencent made a $350 million strategic investment in Kwai—the app “for ordinary people” as described (in Chinese) by Tencent’s CEO Pony Ma. According to a study by McKinsey & Company, the share of China’s middle class in megacities will fall to 16 percent by 2020, down from 40 percent in 2002.

Over half of Kwai’s users live in Tier 3 and 4 cities, says a report by Questmobile in March. Some respondents to the Zhihu thread express concerns over the decadent, lewd minds of small-town Chinese. Others, however, point out that not everyone on Kwai, or in China’s small cities, entertain obscene tastes. If you keep liking obscene content then certainly, Kwai’s smart algorithm will show you more obscene content, one respondent taunts.

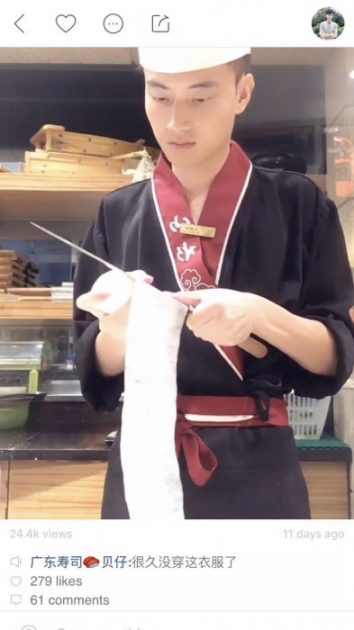

“Of course, the more inciting the content, the more popular it will get,” says Beizai, a 28-year-old Kwai user who works as a sushi chef in Zhongshan, a city south of Guangzhou. Beizai’s sushi-making clips have won him more than 100k followers.

“I like to use Kuaishou because everyone is equal here. Anyone can attract fans, as long as their work is good,” says Wang Xiaodou, a 31-year-old farmer in Zoucheng, a small city near the birthplace of Confucius in Eastern China. Wang, who stopped attending school beyond the fourth grade, started using Kwai a year ago because “friends recommended it.”

Her husband uses Oppo—a popular smartphone brand in China’s lower-tier cities, to film Wang’s daily life, from toiling in the potato field to stoking a fire and making hand-made dumplings. Many of her 500k followers ended up adding her on WeChat, thanking her for documenting moments of the peaceful country life.

“It reminds them of their own childhood life,” says Wang, who came back to the village to take care of her husband who can’t leave home because of a major surgery.

Wang is not alone in this kind of reverse migration. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), China’s migrant population has been in decline since 2015. As of 2016, there are 245 million migrant workers across the nation, 1.71 million fewer than a year ago.

On the contrary, the number of rural migrant workers (农民工)—workers with a rural household registration (户口) who are employed in a city—working locally near their home area has risen by 26% over the past seven years. This in part is due to the slowing income growth for migrant workers in the more prosperous Eastern China. Data from NBS shows that between 2011 and 2016, annual growth rate of monthly income for rural migrant workers dropped from 21.2% to 6.6%.

“No, why would I go to the big cities?” Beizai says. His hometown Hezhou is a 3.5-hour bus ride away, so he can visit his family easily. He is moving back to Hezhou in a few days, for even housing prices in Zhongshan has grown unaffordable with the expected opening of the Shenzhen-Zhongshan Bridge that will make idyllic Zhongshan a second home for the affluent Shenzhen residents.

Other tech giants have also followed the Chinese migrants home. Weibo, once touted as the Twitter of China with a similarly elitist, urban crowd, switched to a lower-tier city, video and live stream-focused strategy following its fall from past glory. In 2014, CEO Wang Gaofei proclaimed his vision (in Chinese) for a comeback plan: “If we want to reach 300 million monthly active users and 100 million daily active users, where would these users come from?” The answer lies in second, third, and even fourth-tier cities, he told his employees in an internal meeting.

While first-tier cities have largely reached smartphone penetration maturity, lower-tier cities were still seeing double digit growth in 2014, according to Nielsen’s research. Weibo has seized this population by pre-loading its app into partnered low-end smartphones.

The NASDAQ-listed company’s rural pivot has proven successful. From 2015 to 2016, Weibo’s MAU grew 66.2% to 312 million (in Chinese), mainly driven by an expanding Tier 3 and 4 user base. On August 9, the company hit a $20 billion valuation (in Chinese) for the first time, with revenue growing at 79% year on year to RMB 1.73 billion ($260 million). Alibaba-backed Momo, once widely considered the “Chinese Tinder”, has also successfully ramped up its Tier 3 and 4 (in Chinese).

Like Beizai, Wang has no regrets over leaving China’s megacities where many have struck it rich. “Everyone has their own desires. For me, being with my family is the biggest source of happiness,” she says, then excuses herself from our WeChat conversation as it’s time to take off for the field.