On June 9, China’s Ministry of Education founded the Department of Off-Campus Education Administration to regulate China’s after-school tutoring industry. During the May 2021 Conference of China’s Central Comprehensively Deepening Reforms Commission, Chinese President Xi Jinping and the conference committee reiterated that new policies would be needed to make school less stressful for students — with the target focused on after-school curriculum-based training centers.

The hammer fell last month when the State Council — China’s chief administrative authority — released new educational policies to reduce students’ workloads and tighten rules on for-profit curriculum tutoring companies.

Chinese students are famous for participating in excessive amounts of private tutoring outside of regular school hours. The government’s reform efforts aim to free Chinese students from their chronic academic stress. And while it’s easy to argue the regulatory changes will be positive for kids, some parents are likely less than thrilled with the reforms.

In part one of our three-part series on China’s crackdown on private curriculum-focused training companies, we introduce the phenomena of ‘chicken parenting’ and explore how anxious parents have fueled China’s enormous for-profit tutoring industry.

“I’ve Forgotten How to Smile”

Kelly Zhou is the head of a Shanghai-based private international kindergarten that offers Chinese-English bilingual education. A veteran in the education industry, she understands the importance of children’s social and emotional wellness. Thus, when one of Zhou’s students, who we’ll identify as C, told her that she is so busy every day that she had forgotten how to smile, she immediately scheduled a chat with C’s mother.

According to Zhou, C was a bright young girl who “was more than prepared to be a kindergartener.” She was polite, intellectual, and articulate. The downside was, she didn’t have many friends because she felt that her peers “were too childish.” She didn’t see the point of befriending her peers because “none of them understood anything.”

At the time, C was 4 years old.

A whopping 60% of children under 15 in China were signed up for at least one private tutoring session in 2019. Photo by Jerry Wang on Unsplash

C’s mother graduated from one of China’s top colleges and was a full-time parent. Every Friday after kindergarten, she would send C to a private English tutor. Afterward, her young daughter would attend other academic-related sessions.

Over the weekend, C would partake in a ballet class, a piano lesson, a painting school, math tutoring, and a sports team. “Pretty packed [schedule] for a 4-year-old,” says Zhou.

“I’m able to offer my kid everything,” C’s mother told Zhou, “And she’s able to manage all that.” The parent didn’t see anything wrong with jam-packing C’s life with extracurricular activities — robbing her child of free time.

Zhou once asked C what part of her life made her happiest. “I’m never happy,” C responded, “I’m tired every day.”

You might also like:

For Graduating Chinese Art Students in London, Covid-19 Has Played Havoc with Their FuturesCovid-19 has had many adverse effects on the world. For art students, they have been robbed of their chance to debut in the art worldArticle Mar 03, 2021

For Graduating Chinese Art Students in London, Covid-19 Has Played Havoc with Their FuturesCovid-19 has had many adverse effects on the world. For art students, they have been robbed of their chance to debut in the art worldArticle Mar 03, 2021

The Chicken Philosophy

The story of C and her mother represents a small yet significant group of Chinese parents: the ‘chicken parents’ (jiwa, 鸡娃, literally ‘chicken kids’). The verb ‘chicken’ (ji, 鸡) comes from ‘chicken blood’ (jixie, 鸡血). The Chinese idiom ‘shot up with chicken blood’ (da le jixie, 打了鸡血) refers to someone with inexhaustible energy, and the phrase ‘chicken parents’ derives from the action of ‘chickening’ one’s children — doing everything to make their kids perfect.

Chicken parents are not the majority of Chinese parents. However, they have quickly garnered the most media attention and have formed a community — or perhaps more accurately, a cult-like community.

In March, Chinese publication Everyday People (Meiri Renwu, 每日人物) published an investigation on chicken parenting that quickly went viral. Having no kids herself, the first-person narrator posed as a Beijingese chicken mom and attempted to join a few prominent chicken parenting WeChat groups. (The narrator’s gender is never explicitly stated in the story. For the sake of convenience, we will use the ‘she/her’ pronouns, based on the concocted identity.)

You might also like:

Why a Generation in China is Coming of Age with Short-SightednessWith growing academic pressure and reliance on technology, one of the world’s highest childhood myopia rates has reached new heightsArticle Feb 25, 2021

Why a Generation in China is Coming of Age with Short-SightednessWith growing academic pressure and reliance on technology, one of the world’s highest childhood myopia rates has reached new heightsArticle Feb 25, 2021

The narrator’s initial attempts to join the groups failed because she did not know the basic slang terms used by chicken parents. Due to her unfamiliarity with chicken parenting, she was deemed “unhelpful for the other parents” and blocked by the group’s moderators.

Communication within these WeChat groups is heavily based upon a collection of euphemistic vocabulary. These groups of parents share resources such as illegal PDFs of English storybooks and discuss success stories of the most competitive kids. They also research the best extracurricular sports and arts programs, organize ridesharing to cram schools, and rant about their children’s inability to be ‘chickened.’

Indeed, the collaborative community of chicken parents is possible because everyone has been verified to be “helpful for other parents.”

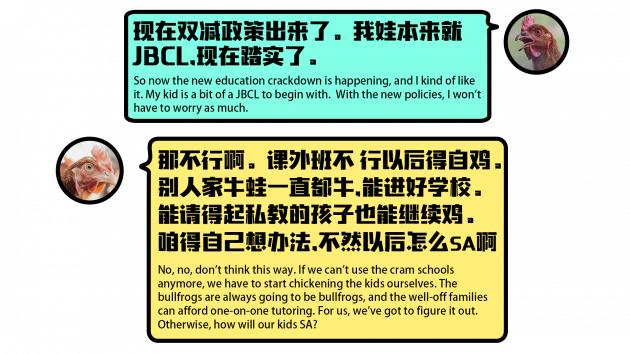

A concocted conversation between two mothers using a healthy dose of chicken parent slang. JBCL (an acronym for 鸡不出来, ji bu chu lai) means “can’t be chickened” or “chickening with no effect,” while bullfrogs (牛蛙, niuwa) are “super-smart kids.” SA (上岸; shang’an) refers to “ending the long chickening journey” or “getting into a good school.” Image created by Sabina Islas

Some of these groups even discuss good places to take children to rest their eyes. Eye-relaxation spots are allegedly needed to ensure that kids are visually able to continue studying. According to a parent, “if [the children] become myopic now, how can they take more tutoring sessions in the future?”

K, who also asked to remain anonymous, is a facilitator of several chicken-parenting WeChat groups and a 15-year veteran in the education industry. He explains to RADII how he manages his WeChat groups:

“Before we add new parents to our group chats, we always verify their identity — who they are, where their kids go to school, etc. We want to make sure that the parents subscribe to the same chickening ideology and thus feel comfortable sharing their thoughts.”

K also has different groups for parents, depending on how active they are and how competitive their children are. Carrying along with chicken parents’ long-lasting tradition of food-focused vocabulary, K named his groups ‘Kobe Beef,’ ‘Hida Beef,’ ‘Miyazaki Beef,’ and ‘Sendai Beef,’ among other Japanese Wagyu terms.

Unsurprisingly, the names of the most high-quality and luxurious Wagyu varieties are reserved for the more prestigious chicken parenting groups.

“I do it the same way as I’d manage a celebrity fan group,” K tells us. “The more you participate, the higher status you achieve.”

Except in these groups, the focus of adoration is the concept of chicken parenting.

“The parents love it. Their chicken kids at school are the rare ones, and they are the weirdos among other parents,” says K. “But here, everyone shares the same parenting ideology; they do the same things to their kids. Nobody challenges them. I can’t even recall the last time when there was a big argument in any of these groups.”

“Here,” K adds, “the parents feel that they belong.”

Operating an Excavator

If chicken parents were the only parents who enrolled their kids in cram schools, the government might not need the Deepening Reform Commission to rein in the private education industry. According to a 2019 survey across Chinese cities, 60% of children under 15 were signed up for at least one private tutoring session.

S, another alias, is among this 60% of parents, sending her third-grade daughter to three cram school sessions per week. However, S herself is not anxious about her daughter’s education and future. Instead, she sees cram school as something inevitable, telling us, “It’s what China’s education is like today. Everyone else is getting tutored; how can you not play by these rules?”

In addition to curriculum-based training centers, many chicken parents sign their children up for sports and arts programs. Photo by Jerry Wang on Unsplash

Kelly Zhou also falls among this broader group of parents. However much she disagrees with her client’s chicken parenting philosophy, she still feels the need to sign her son up for weekend math courses.

“I explained my reasoning to my son,” she says, “he said that he had a dream job for the future. I told him, ‘If you don’t start studying a bit more now, you won’t make it that far.’ Worst case scenario, he won’t go to college. And I asked him, ‘Will you be okay with that?’”

Part of Zhou’s fear originates from the fact that China is allegedly planning to shrink the number of students admitted to high school and, as a result, college.

You might also like:

Help this NGO Change Girls’ Lives in Rural ChinaFor 15 years, Educating Girls in Rural China (EGRC) has changed the lives of thousands of young womenArticle Aug 07, 2020

Help this NGO Change Girls’ Lives in Rural ChinaFor 15 years, Educating Girls in Rural China (EGRC) has changed the lives of thousands of young womenArticle Aug 07, 2020

Rumors have been widely circulating on the internet that 50% of China’s middle-school graduates will go to vocational school in the future. Chinese state-backed media People.cn has debunked the rumor, but it’s apparent that Chinese parents are worried about their children not being admitted to high school and college.

“The difference in salary and social status of white-collar workers versus blue-collar workers, the gap is simply too wide,” says Zhou. “Think about how Chinese parents scold their kids, ‘If you don’t study, in the future you’ll be working on a construction site operating an excavator.’ I’m personally not against my kid operating an excavator, but who’d like to see their kids being viewed as inferior?”

K agrees with Zhou. Reflecting on his experience with parents, he tells RADII, “When parents send their kids to cram schools, their expectation for their kids’ future increases.” In other words, those who have taken tutoring lessons will be seen as failures if they end up in a vocational school or a community college.

Chinese parents are worried about their children not being able to attend high school and college. Image via Depositphotos

“Now that cram schools are to be cancelled, parents won’t have false hope of their kids getting into college,” K adds. “So, when their kids get into a vocational school and go work in a factory, the parents will be mentally prepared.”

Unaware of their parents’ and educators’ discussions above, many young Chinese children are trapped in the system of cram schools. They feel overworked when taking more tutoring classes than they desire; when they don’t, they feel anxiety about themselves and their parents’ expectations, potentially pushing them into schooling after regular classes end.

But for cram schools and training centers to thrive, it is not enough to tickle the interests of children. In part two of our series on China’s crackdown on private curriculum-based training companies, we’ll explore how cram schools win the hearts — and wallets — of parents.

Cover image by Jerry Wang on Unsplash