Selfies.

2003’s seemingly minor addition of a second, front-facing camera on the Sony Ericsson Z1010 forever changed how we experience our increasingly digital world. Now selfies are inescapable, as present on our picturesque vacations as they are in our cybernetic love lives. There’s a cultural cycle that takes place when selfies are introduced – novelty, ridicule, innovation, acceptance. It goes from hey, let’s take a selfie, to why does she do that duck face in every picture? to Snapchat has interactive filters now! to the lyrics wait, let me take a selfie constituting a plausible theme for a hit radio single (disclaimer: we hate The Chainsmokers). But in China there’s one more stage in the cycle – marketability.

Billboards, subway ads, TV screens and mobile phones are plastered with the image of the selfie. And it’s not the selfie itself: it’s the act of taking one.

A subway ad I saw yesterday

Take this one for instance. Two girls in kimonos sit in front of a sushi spread. They pause to snap a selfie. Posing for the camera, full of likable, youthful energy, the two girls hold up their favorite product – Lion King toothpaste, available online at Tmall. The sushi, the toothpaste, and the selfie aren’t really related in any way. But the girls are beautiful. They’re having a more photogenic time than you. And they’re about to win status and admiration from their peers when the photo goes up. Their white teeth sparkle as if to say, this could be you.

I noticed the iconography of the selfie-taker firsthand while working on a project for the Guilin tourism bureau. I was hosting a video travel feature, checking off all the boxes in one of China’s biggest tourist destinations while a camera crew followed to document every moment. Every so often our director would stop and hand us an off-brand GoPro on a selfie stick. You take selfie, and we film you, he told us. The GoPro didn’t even have to be on. The video quality was bad, not usable in the final product – but it didn’t matter. The director just wanted a shot that would convey the idea of us sharing our experience online, where it would be seen by our loving friends and acquaintances.

No, the GoPro is not on

The actual popularity of the selfie-taker as a marketing image seems excessive, but it’s only natural if you consider the origins of cell phone culture in China. The arrival of the first true wave of cell phones in the country culminated in 2003’s Cell Phone, a box office smash hit directed by master of “cool” cinema Feng Xiaogang, and the year’s most profitable Chinese film. The main plot device of the film is the stylish and desirable Motorola 388C, which takes the characters on a journey of adultery, romance, comedy and suspense while handily showcasing the phone’s biggest features. The film was a hit across the board, turning its primary sponsor Motorola into the most talked-about cell phone brand in the country. Immediately afterwards, Motorola launched its music and entertainment platform, alongside the supremely successful “Hello Moto” advertising campaign. Cell phones had become intertwined with the rapidly emerging idea of mobile music, cementing their association with coolness and youth.

Today the culture surrounding cell phones has changed a lot, while also managing to stay the same. Our phones are much, much more than fifteen-buttoned boxes for calling and sending text messages, and that rings especially true in China. People here reach for their phones any time they need to buy a coffee, pay their landlord, or unlock a public bike. QR codes, the scrambled mosaic boxes that the west carelessly left behind, are ready for scanning everywhere you look, jump off points of digital connection in our three-dimensional world.

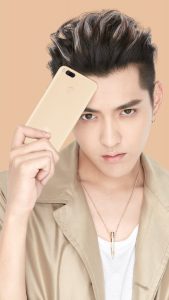

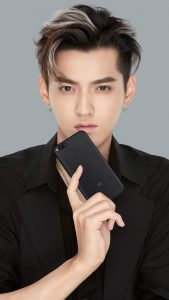

Most advertisements for cell phones in China just consist of a pretty celebrity holding the product in a counterproductive grip

At the same time, the energy surrounding them has remained surprisingly similar. Every phone wants to be the hippest, the most stylish, the most youthful, the most international. iPhone is still the heavyweight symbol of status as far as mobile phones go, but local brands like Xiaomi, Huawei, and Oppo have jumped into the race. Cell phone marketing here tends to focus more on the image than on the capabilities of the product itself, and most graphic advertisements for cell phones just consist of a pretty celebrity holding the product in a counterproductive grip.

China’s current “it boy”, ‘Hip Hop of China’ judge Kris Wu, failing to use the Xiaomi phone in any human way

On a macro level, China as a consumer base is still wrapped up with two things: the pursuit of Western products and image, and the performance of that image to their peers. Buyers eat up Gucci handbags and name brand fashion, real or fake, as a way of wrapping themselves in a visible international veneer. Tables at nightclubs are bought up by teenage kids from wealthy families, who come only to be seen. They stay at the tables rather than the dance floor, texting aimlessly and ordering bottles of champagne, which are decked out in eye-catching pyrotechnic sparklers, to be conspicuously paraded to their table by models. They take the pictures to post later, and delve back into their digital worlds.

Another subway ad I snapped in 2015, advertising a job recruitment website. Featuring the world’s most punchable face

The selfie-taker, then, is the intersection of all these things. Cell phones, consumer products, and social image. The selfie-taker is international, young, cool. The selfie-taker is equipped with the products you need to succeed, whether that be a cell phone or something else entirely. Most of all, the selfie-taker is poised to demonstrate his or her personal value to the world at large. The image of someone taking a selfie embodies both the act of demonstrating value, as well as the value itself that is worth demonstrating. A selfie-taker in an exotic locale says my international life is worth sharing. A selfie-taker in a button-down shirt and tie says my professional success is worth sharing. Two kimono-clad selfie-takers with white teeth say my physical appearance is worth sharing.

The selfie-taker is the intersection of all these things: cell phones, consumer products, social image

The selfie itself is only a vehicle. By connecting the selfie to the product, whatever that happens to be, the ad creates a value demonstration of its own. It lets the viewer know that their product is not only capable of making your life better, but that your improved life will be seen and appreciated by everyone you know. Selfies in ads might seem eerily common here. But when you consider the context of a rapidly changing 21st century China where image is everything, it only makes sense.