If you’re in China at this exact moment in time, you can’t avoid it.

Freestyle.

The word is everywhere right now. Say “freestyle” aloud on the street and see if any heads turn. Look around you and you’ll find the word in the mouths of young people, or written in huge letters on live-streamed internet talk shows, or used as supporting copy in advertisements for milk-flavored biscuits. How did this happen?

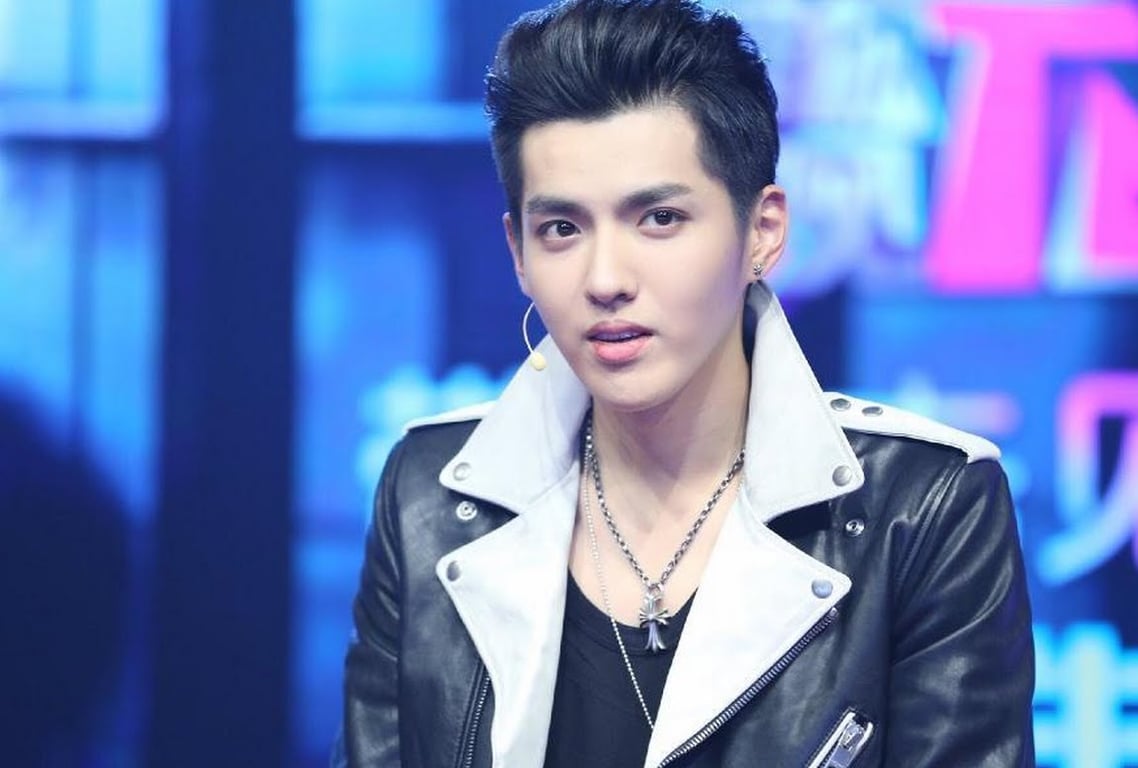

If you’re a regular Radii reader, you’ll know the answer, which we broke down in our look at newcomer hit TV show The Rap of China. The competitive hip hop show’s first episode got more than they expected when celebrity judge Kris Wu stared down the very first contestant and asked him the now-infamous 有freestyle吗? (you got a freestyle?).

The meme took off at lightspeed, with freestyle holding the top trending spot on Weibo for several days. GIFs of Kris Wu asking people if they have freestyles are on every phone screen. On a surface level, it seems simple enough: hip hop is just now beginning to catch on in China, and it’s not hard for a nation to be united by a shared gag on a widely-watched TV show. But there’s more to it than that – freestyle, like so many words before it, has taken on a life of its own; it is no longer contained to the use, meaning, or context, from whence it came. We’ve officially lost control of freestyle.

Over the weekend, some friends and I visited the M50 art district’s outdoor Urban Aesthetics Fair in Shanghai. Glancing at a WeChat ad, I was neither shocked nor excited to find out the fair was loosely freestyle-themed:

You don’t need to read Chinese to see what I’m getting at.

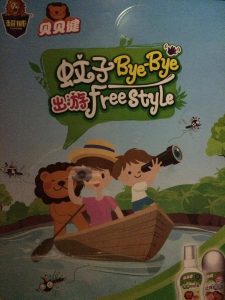

What did surprise me though, was that when we arrived, there was a group of rappers spitting bars with little or no preparation – a performance commonly referred to as a freestyle. It might seem obvious at first, but I was floored to find out the freestyle-themed aesthetics fair had actual freestyles happening. Consider, then, that this is the freestyle I encountered just a few days earlier:

Mosquitos bye bye, going out freestyle, reads the advertisement for mosquito repellant. Pictured are a smiling mother and her child exploring a nature scene, guided by a happy lion, as mosquitos die all around them. Does it have anything to do with improvisational hip hop rhymes over smooth beats? Absolutely not. But to a room full of marketing execs, squinting unknowingly at the top trending Weibo words, it doesn’t matter. Suddenly, everything is freestyle.

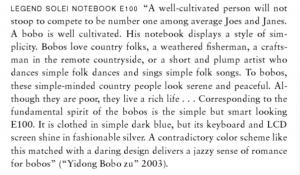

The phenomenon of trendy English words being squeezed dry for everything they’re worth is nothing new. In his book Brand New China, scholar Jing Wang writes on a particular example – bourgeois bohemians, or bobos. Author David Brooks coined the term to describe “highly creative folk who have one foot in the bohemian world of creativity and another in the bourgeois realm of ambition and worldly success.” Little did he know, this is exactly what a rapidly-emerging China craved in 2002. The wealthy elite jumped at the chance to alter the pervasive anti-rich narrative, and the citizens of second-tier cities had a quick framework they could use to emulate the affluent bobos of Shanghai and Beijing. Bobo became number three on the year’s list of top ten internet words, and everyone tried to cash in on the craze, from hastily-erected Bobo Cafes, to luxury apartment complexes (Do you look for something cool about a refrigerator rather than its cooling function when you shop for one? Is it unbearable if your living space does not give you a poetic sense of life? If you answered yes to either question, you’re a prospective bobo, and are qualified for a surprise gift and free tour of the apartment complex). Here’s an ad from that time for a completely normal laptop computer:

Obviously, form follows function when it comes to English buzzwords. The actual meaning and origin of the words is secondary to how they can be used by (or on) a society at large, and there have been countless examples in the years between bobo and freestyle. Someone who’s lived in Shanghai or Beijing in the past few years could probably attest to the amount of concept and lifestyle going around. Concept malls that are just malls, lifestyle bubble tea that’s just bubble tea. In fact, it’s my own belief that the lifestyle craze of the past year or two set the linguistic foundation for freestyle’s ascension to the throne.

The meaning of the words themselves is not important. We’ve learned this lesson from millions of questionable T-shirts, street signs, and restaurant names, but it rings especially true in the context of trending buzzwords. A freestyle is no longer just a freestyle, a bobo not just a bobo. They become more than that, transforming into wings of western identity, which China’s consumer class – young and old – can latch onto and ride to new heights as they continue to discover their own place in a rapidly connecting world.