I recently rediscovered a cultural practice while lending a friend a hand. He had asked me to help clean up a heap of junk that had accumulated in his uncle’s home.

Childless and unwed, the 73-year-old chain-smoker from Hong Kong had been admitted to a care home in Vancouver, Canada.

I arrived at Mr. Chan’s house as promised.

A decades-long lack of female supervision combined with severe dementia from Alzheimer’s — resulting in an inability to recognize kitchen appliances — had led to some foul-smelling and occasionally hilarious discoveries in his home.

For example, I found frozen dumplings securely stored in the bedroom safe, dirty woks in the toilet, and a red metal garbage can in the fridge.

Except that it wasn’t a garbage can. A closer look revealed that it was a metal can used for burning offerings during the Hungry Ghost Festival, a traditional Taoist and Buddhist festival held in some parts of East Asia.

Practitioners believe that the gates to the spirit world open once a year, on the 15th night of the seventh month of the lunar calendar, to be specific (August 12 this year). Potentially angry and hungry, the dead are said to roam the earth again and might seek out their living relatives on this day.

Discovering the metal container revived memories of my time living in Guangzhou and Hong Kong: Their streets are lined with similar receptacles every Ghost Festival. You’d often spot the elderly placing oranges and bottled drinks on the ground, burning joss paper or spirit money, and keeping the fire going in the pots.

It gave me the creeps to imagine invisible ancestors resembling Chinese vampires stuffing their faces next to blazing metal cans at the stroke of midnight.

This mental image recently came to mind while viewing American poet Jane Wong’s recent exhibition, After Preparing the Altar, The Ghosts Feast Feverishly, at the Richmond Art Gallery in Canada. The installation was first presented at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle in 2019.

Jane Wong’s exhibition, After Preparing the Altar, The Ghosts Feast Feverishly, at the Richmond Art Gallery in Canada. Image via the artist

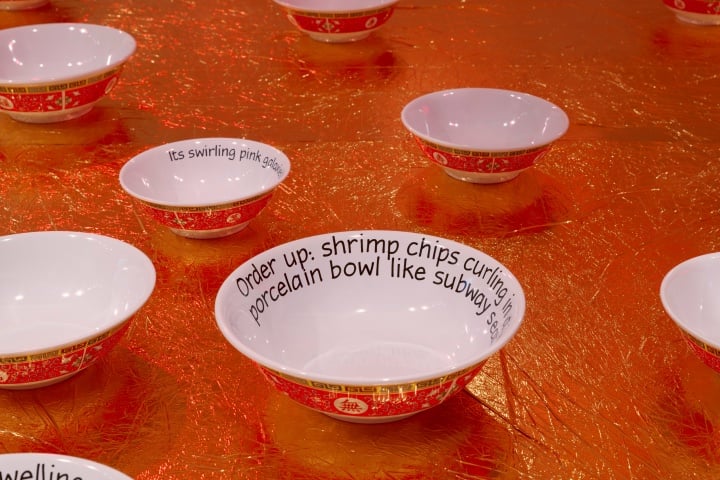

Covered with a bright gold layer that looked exactly like joss paper, a 15-foot wide table took center stage in the gallery. Bowls imprinted with fragments of a poem by Wong — also titled After Preparing the Altar, The Ghosts Feast Feverishly — were arranged on the table, while plastic bags filled with fake fruit and flowers hung from above.

The installation served as an invitation to gather around the table, not unlike families during the Hungry Ghost Festival, and to piece the poem together.

Written in the voice of Wong’s ancestral ghosts, the poem conveys impatient requests from spirits yearning to satiate their hunger, and provides glimpses of the poet’s own life.

“We want the marbled fat of steak and all its swirling pink galaxies…. Order up! Pickled cucumbers piled like logs for a fire, like fat limbs we pepper and succulent in,” said the ghosts in an imagined conversation with a little girl.

“Did our mouths buckle at the sight of you devouring slice after slice of pizza and the greasy box too? Does this frontier swoon for you?”

Wong, a scholar of Asian American poetry and poetics, holds an M.F.A. in poetry, a Ph.D. in English, and is an associate professor of creative writing at Western Washington University. A Kundiman fellow, she is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize and James W. Ray Distinguished Artist Award for Washington Artists.

Like her work, the poet’s life is full of fragmented memories and mysteriously missing pieces. As the daughter of restaurateurs in New Jersey in the 1980s, she grew up making wontons and cleaning ‘shrimp poop’ until the sixth grade.

When Wong was 23, she lived in Hong Kong for a year as a Fulbright fellow. According to her, it was “life-changing, living abroad and fucking up Cantonese.”

During this period of her life, she embarked on a momentous trip to her mother’s ancestral village near Taishan in China’s southern province of Guangdong to celebrate Qingming Festival.

Also known as Tomb Sweeping Day, the traditional Chinese festival sees families visiting cemeteries, cleaning graves, and paying their respects to their ancestors. Some parts of China involve traditions like feasting on whole roasted pigs, downing bottles of China’s national spirit baijiu, and burning fake paper luxury items with incredibly realistic details, such as mansions (complete with servants), Gucci bags, iPhones, MacBooks, and Lamborghinis.

During one interview, Wong recalls, “That was a major party; firecrackers this way, funeral money that way, yelling, eating.” However, the villagers would return to their frugal ways after the feast. The idea of coming together for the sake of one’s lost ancestors, splurging on the underworld, and returning to scarcity resonated with Wong.

Her mother was born at the tail end of China’s Great Leap Forward, the Maoist industrialization campaign during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Wong’s grandparents were likely among those who starved to death at this time, but her family never spoke about the possibility. Certain themes — missing histories, ghosts, hunger, gluttony, and immigrant cultures existing in different worlds — are now core to Wong’s works.

A recurring theme in her poems is “going toward the ghost,” a method she uses to reclaim forgotten histories.

“I want my ghosts around,” explained Wong. “I want to recognize and say to my ghosts, ‘I know that you are hungry and I want to feed you. The only way I can, in the afterlife, is through poetry.’”

This theme stands true in another poem by Wong titled After He Travels Through Ash, My Grandfather Speaks, which the author penned in the voice of her grandfather, who struggled with fading memories:

“Can you believe it, how I’ve forgotten the sounds of cars, the sounds of buses leaving without me in huffs of impatience? I don’t remember what a broken toothpick sounds like, or how Chinese soap operas loop like precious snakes along my apartment’s walls.”

Wong also honors her grandmother in A Cosmology by writing, “The rotting head of broccoli in my grandmother’s bowl blooms with power… I set an altar, the altar billows with ferns good in any soup.”

Wong’s 2019 exhibition After Preparing the Altar, the Ghosts Feast Feverishly. Image by Jueqian Fang, via the Frye Art Museum

By interpreting and honoring the experiences of her loved ones — who rest in graves or urns — through poems, Wong has found a way to fill the holes in her family history.

I think about this while peeking inside Mr. Chan’s red metal can, which contains some ash and half-burnt spirit money, pulling on a pair of gloves and carefully transferring said container to his backyard.

While leaving the home, I tried to ignore the imaginary spirits gathered around the can and stop reciting Wong’s words: “The marbled fat of steak and all its swirling pink galaxies… Pickled cucumbers piled like logs for a fire, like fat limbs we pepper and succulent in…”

After nervously whipping out my iPhone, I did a quick Google search for ‘Hungry Ghost Festival 2022’ before scoffing, “Ha! Not today. Come back on August 12!”

Wong’s upcoming memoir ‘Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City,’ a reference to a Bruce Springsteen song, will be released in 2023. While the book touches on the hardships of immigrant families, it also has humorous bits that she hopes will make readers laugh.

Cover photo via Helene Christensen