Dong Yu has worked for a local piano manufacturer for over 25 years. Living in northeastern China’s Liaoning province, the 44-year-old painter’s day-to-day work consists of manual labor. But in his downtime, he pursues a relaxing and rewarding hobby: playing the piano.

Over the past two decades, Dong has used his spare time to teach himself how to play the instrument. “I had this whole perception that things like pianos were out of my league, growing up in a poor family,” he says. “It was September 13, 1996 — the first day of my job — that I ever really got close to a piano.”

His practice of the instrument has seemingly paid off. Aided by the explosion in popularity of short video platforms in China, Dong is now a star on Douyin — China’s version of TikTok — and its main China-based competitor, Kuaishou.

Related:

A Quick Guide to China’s Competing Short Video AppsBaidu, Alibaba, and Tencent have all launched Vine-like short video apps in recent months, joining the relatively established offerings of Kuaishou and DouyinArticle Sep 19, 2018

A Quick Guide to China’s Competing Short Video AppsBaidu, Alibaba, and Tencent have all launched Vine-like short video apps in recent months, joining the relatively established offerings of Kuaishou and DouyinArticle Sep 19, 2018

His first taste of virality came in May 2019, when a truck driver uploaded a video of him in workwear playing “I Love You China” (我爱你中国). The video, he recalls, racked up 16 million views within hours. His story was then picked up by Tencent News, CCTV and China’s largest newspaper People’s Daily.

In the aftermath of his viral hit, Dong decided to register his own account on Kuaishou and found repeat success, garnering more than 485,000 views on his debut video. Today, the unlikely social media star has over 300,000 fans, while one of his most recent videos notched half a million views.

Dong Yu’s story of overnight fame is one of a number on Kuaishou, adding to the platform’s reputation as a place for people with niche talents outside major Chinese cities to reach huge audiences.

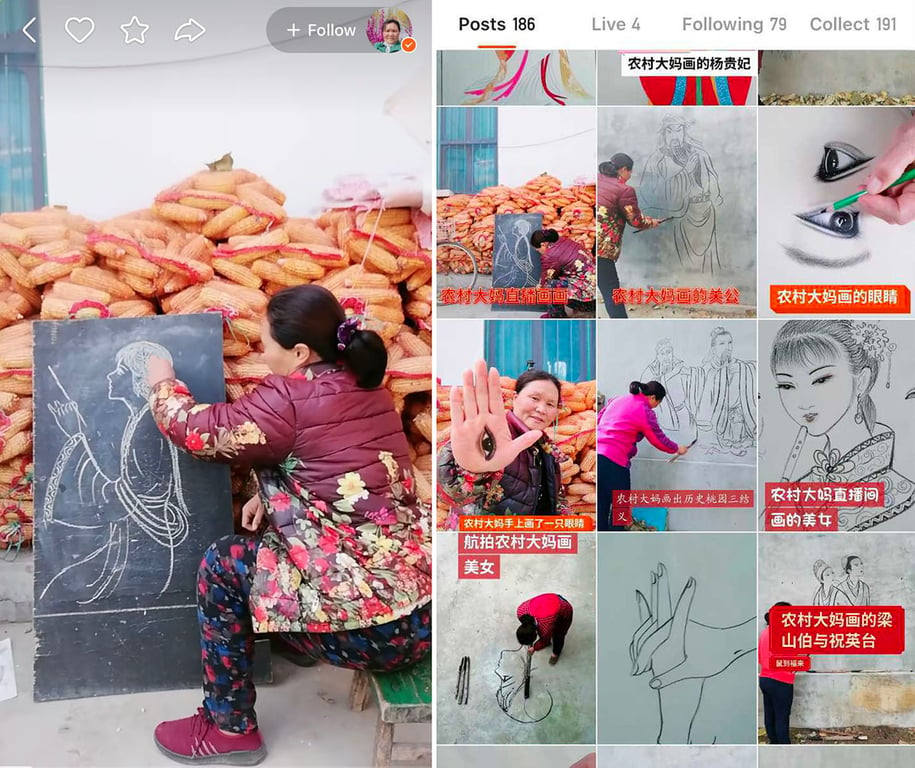

In his videos, Dong Yu is usually dressed in workman’s overalls and sitting in a dusty factory room; the romanticism of his tale as a working class, self-taught pianist has also no doubt added to his appeal. Equally popular videos feature users showcasing their dancing and painting talents against an unlikely backdrop, such as construction sites and corn fields.

A self-taught artist with 1.9 million followers on Kuaishou (image: Kuaishou)

But while a quarter of China’s rural population are Kuaishou users, the short video app’s reputation as a platform for rural voices and niches seems to be changing.

Kuaishou’s Slow Rise

Kuaishou is the oldest short video platform in China. First founded back in 2011 as a GIF maker, it was only in 2016 that the short video app became popular nationwide, when netizens picked up on the platform’s plethora of videos that focused on Chinese rural life.

Rather than lip-syncing and dancing to music — the kind of videos that TikTok and its Chinese version Douyin was first known for — young people in small cities and remote towns have used Kuaishou as a way to connect to the outside world and, in return, turn the spotlight onto themselves.

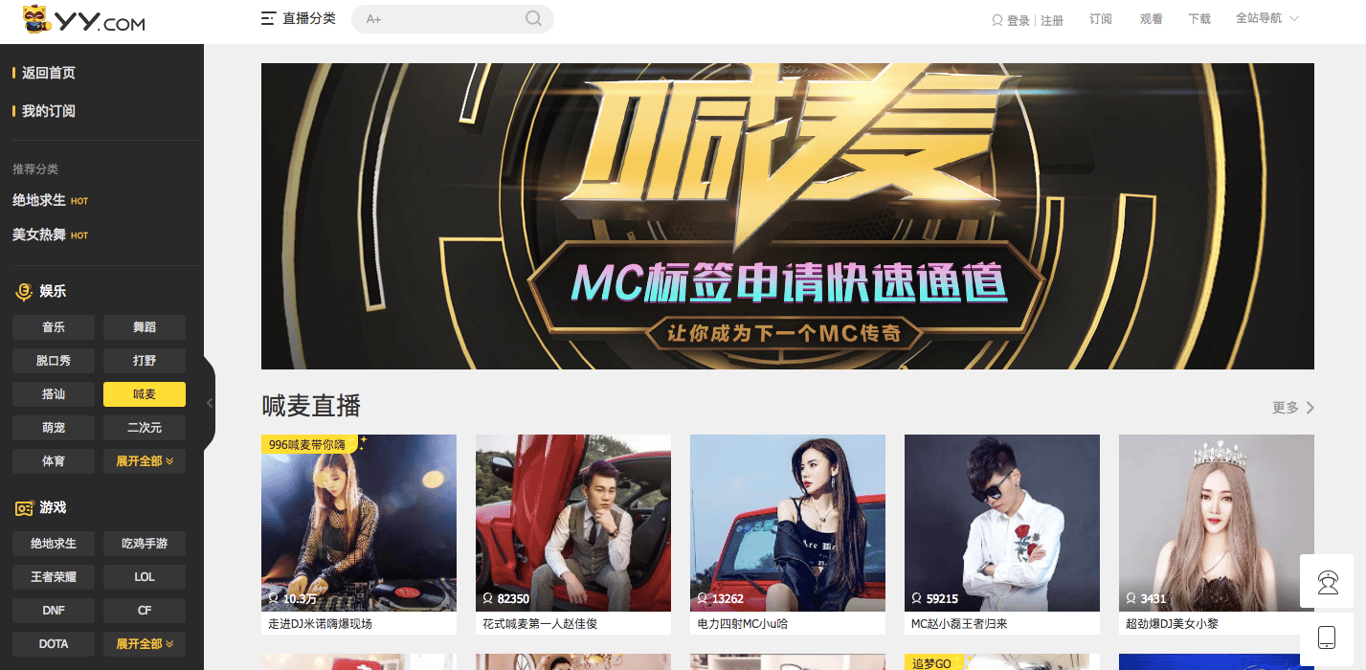

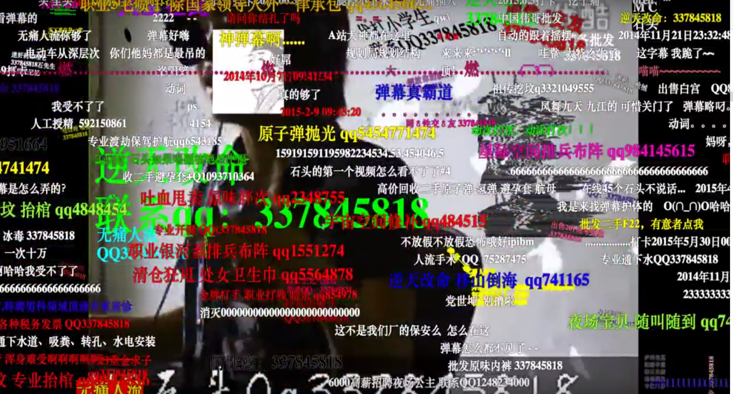

The platform was central to the so-called tuwei (土味) style of video, which offered glimpses into life in the countryside and have since taken the internet by storm. Tuwei videos have also spurred viral fads such as the social shake — a dance similar to 2013’s “Harlem Shake” — and hanmai (喊麦, or “shouting wheat”) rap music videos.

Related:

China’s Hated-On Hanmai MCs Get No Love for Their “Lower-Tier” RapsThe controversial style of Chinese hip hop music has been brought back into the limelight recently. But is it any good?Article Apr 29, 2020

China’s Hated-On Hanmai MCs Get No Love for Their “Lower-Tier” RapsThe controversial style of Chinese hip hop music has been brought back into the limelight recently. But is it any good?Article Apr 29, 2020

Doubling down on its reputation as a platform for rural users, Kuaishou published in-depth reports about this demographic in 2019 — one specifically on the user behaviors of small-town youth, and another on poverty alleviation in the country’s poorest areas.

Kuaishou has always professed to be a “platform for the people,” traditionally targeting users in lower-tier cities and small towns. It adopted a decentralized algorithm in its early days, thereby leveling the playing field for its would-be-influencers, and promoted users with less followers to its trending page. It has also managed to evade celebrity endorsement for most of its lifetime.

Shedding its Earthy Image?

In recent years, however, Kuaishou has been forced to switch up its priorities in order to welcome a wider user base, and reach users in the country’s larger cities.

For instance, Kuaishou has seemingly eschewed its “everyman” image by adding a number of celebrity endorsements to the platform. In June 2020, Jay Chou, one of the most popular pop stars in China, joined Kuaishou for his first-ever livestream on the platform, attracting 10 million followers in less than three days. Earlier in the year, Chinese pianist Lang Lang livestreamed a public piano class and garnered 3 million views in an hour.

It begs the question as to where the platform is headed.

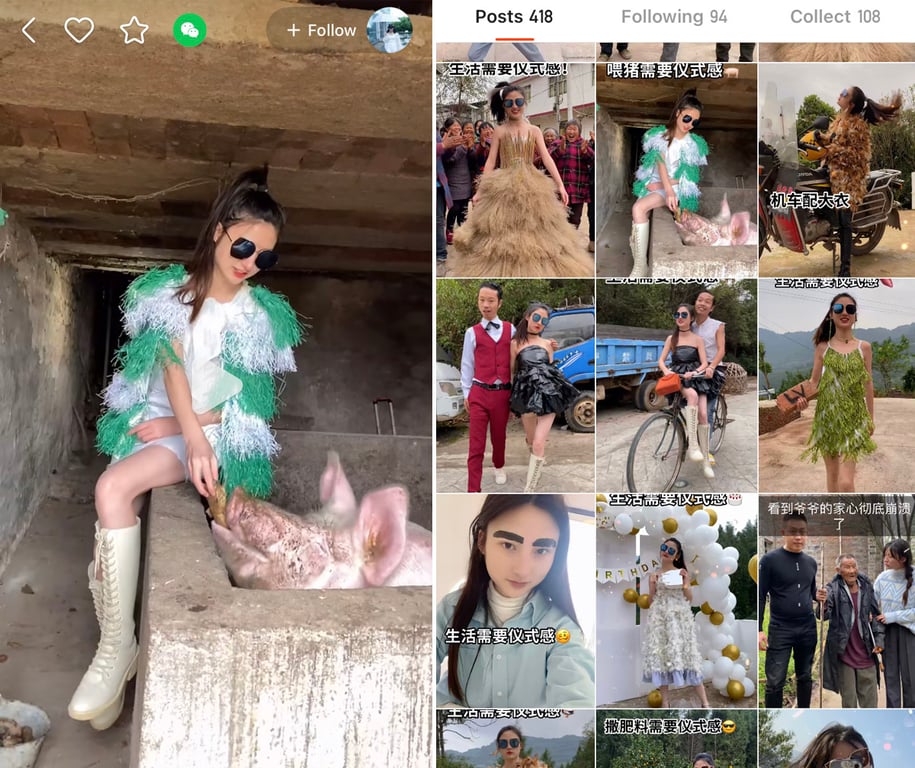

A rural fashion blogger and designer with over 4.3 million followers (image: Kuaishou)

As the company angles for an IPO on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange within the first two months of 2021, the heat is on for Kuaishou to open itself up to a wider audience in its home country.

One reason for this may be that Kuaishou was among the Chinese apps banned by the Indian government last year, losing them an important foreign market in their overseas expansion. These developments occurred the same year as TikTok — the international version of Kuaishou’s leading competitor, Douyin — faced increased scrutiny and executive orders to sell its US operations to an American company.

The race to capture a wider audience has been noticeable in both Douyin’s and Kuaishou’s most recent user demographics. While each had largely divergent strategies years ago, they have been finding common ground lately, especially in regard to where their users are based. According to the latest reports on user demographics from each of the two video giants, the percentage of their users in different tiers of China is gradually becoming more similar, augmenting the competition between them and forcing a platform like Kuaishou to find new ways of advertising.

Particularly pressing for Kuaishou is that the gap in number between both platforms’ active users still appears to be quite large. Douyin has 600 million daily active users as of August 2020, while Kuaishou has only 258 million as of February 2020.

While this increased competition and urgency to expand is feeding into the changing face of Kuaishou, another reason for the app’s shifting strategy is the criticism it faced in 2018, when CCTV accused the platform of publishing vulgar content — in particular, videos that spotlighted teenage mothers in China.

Kuaishou’s CEO, Su Hua, apologized at the time of the controversy, agreeing that the videos could have a negative impact on society and vowed a regulatory crackdown on “unhealthy” content. Soon after, videos that the app boosted began to echo the government’s deliberate efforts to promote positivity in the media.

Related:

Shamanic Rituals and Shaking Shoes: Here’s What Censors Are Looking For on China’s Short Video AppsArticle Jan 15, 2019

Shamanic Rituals and Shaking Shoes: Here’s What Censors Are Looking For on China’s Short Video AppsArticle Jan 15, 2019

This seems to be part of the reason why media outlets reported on Dong’s story in the first place. “I believe one of the reasons that people like me,” he says, “is perhaps I have the ‘positive energy’ that society is trying to promote.”

Where Does Kuaishou Stand Now?

Despite struggling to attract users from big cities, Kuaishou hasn’t abandoned its rural demographic altogether.

Poverty alleviation has to date been one of the key pillars of Kuaishou’s publicized mission. After launching its Happy Countryside rural development project in 2018, Kuaishou started a Social Impact Institute to “support the development of sustainable businesses for entrepreneurs hailing from low-income households,” according to a 2019 press release.

Users from impoverished rural backgrounds were said to have made 2.8 billion USD in revenue on Kuaishou in 2018, and among the 25.7 million users that earned income on the platform from June 2018 to 2019, over one-fourth were in rural areas.

A large percent of that revenue has come from livestreamed ecommerce. Zhang Fei, a rural government official from Sichuan province, helped sell apples and matsutake mushrooms grown in his community in 2019, gaining over 1.56 million followers in the process. The same year, he also managed to facilitate a 500 million RMB peppercorn contract for the village.

Though Kuaishou’s official and unofficial poverty alleviation efforts are ongoing, the platform’s image as a hub for portraits of rural life has nonetheless been changing. Zhuo Ma, a female Kuaishou user living in a suburb of northwestern Qinghai province, says she now mainly uses Kuaishou to “watch celebrities livestreaming and selling products, like clothes, makeup and household items.” “I don’t use Douyin,” she adds, “because I don’t know how to use it.”

First introduced in 2016, Kuaishou’s livestream feature has become one of its main revenue streams. According to its prospectus for the IPO that was just submitted, it now makes up over two-thirds of its total revenue, indicating its heavy reliance on streaming services.

Kuaishou’s intention of massive global expansion has left people wondering whether its interest in amplifying voices from all parts of the country will change. “I haven’t seen a lot of videos from rural areas on Kuaishou since I joined half a year ago,” says Zhong Qi, a 28-year-old Kuaishou user living in Shanghai. “I basically just watch food content on it now.”

Yet for people like pianist Dong Yu, uplifting stories such as his own are still a driving force that leads people to Kuaishou. “It provides a stage for ordinary people, whose voices it otherwise would be difficult to hear,” he says.

But who knows for how long this perception will last?

Cover Image: Mayura Jain

MC Shitou: Icon of a Fading Internet Subculture