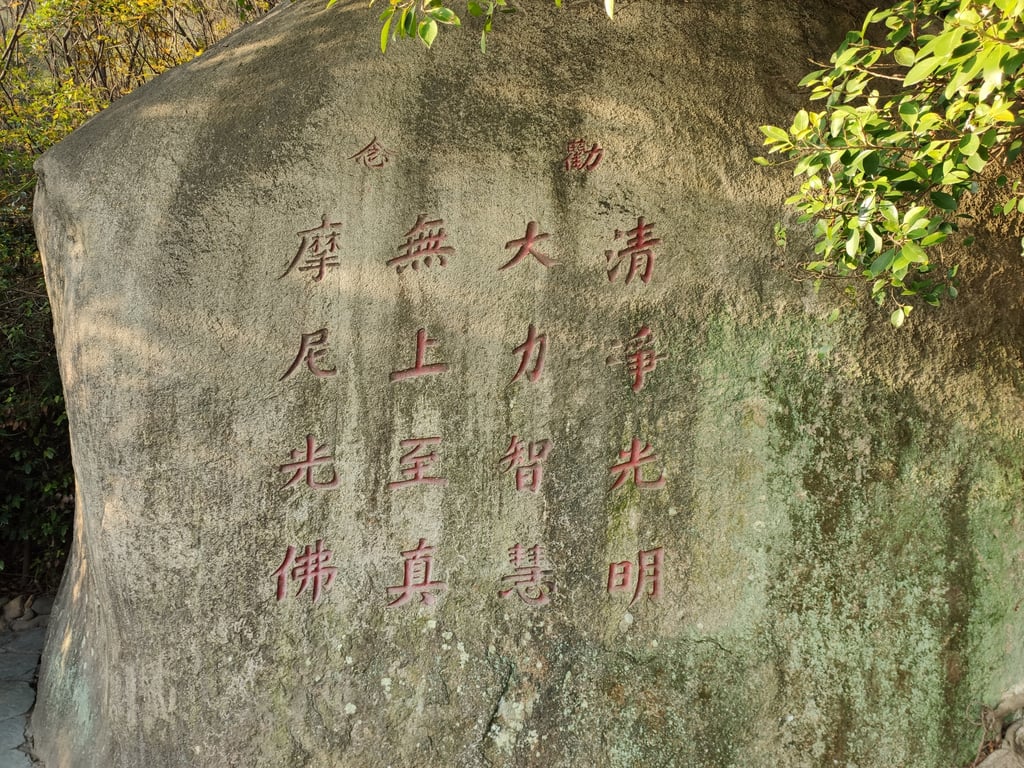

Over a century before Columbus arrived in the Americas, followers of a now-extinct faith carved the likeness of their prophet into a large boulder on a mountainside in China’s southeastern Fujian province. The figure in stone: Mani, an Iranian man who founded Manichaeism, an early rival to Christianity. Mani’s religion suffered extensive persecution during its tenure, at the hands of Roman, Persian and Chinese leaders, and by the 14th century, the religion had fallen by the wayside.

Despite once counting followers from France to the Pacific Ocean, in 2020, there isn’t much left of Manichaeism in terms of physical ruins. Surprisingly, the last extant Manichaean temple exists not in the modern-day countries that compose what was once Persia and Mesopotamia, but in Jinjiang, an industrial settlement of over two million people that is part of the southern Chinese city of Quanzhou.

In mid-2018, a close friend relayed the story of Jinjiang’s unique shrine to the largely forgotten Persian prophet Mani. A quick and always questionable Wikipedia search offered insight — and questions. According to the popular free online encyclopedia: “In modern China, Manichaean groups are still active in southern provinces, especially in Quanzhou and around Cao’an, the only Manichaean temple that has survived until today.”

This poorly cited Wikipedia entry led to more questions: How did Manichaeism get to China in the first place? Are there still Mani followers in the officially atheist People’s Republic of China, and is the temple at Jinjiang the last Manichaean temple in the world?

Light and Darkness

Once counted among the most widespread religions in the world, Manichaeism began in the 3rd century CE in Sassanid Persia, in Mesopotamia. A spiritual amalgamation of sorts, the faith combined elements of Zoroastrianism, early Christianity, Gnosticism, and even Buddhism, and was founded by the Prophet Mani.

Many fantastic works have been written on Mani and the religion he founded (Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China by Samuel Lieu is recommended reading), and to offer an in-depth history of either here is impractical. Instead, here’s something of a jump-course.

Mani, Zoroaster, Buddha, and Jesus

Boiled down to its most basic elements, Manichaeism tells the story of the World of the Light, a spiritual realm, and the material-based World of Darkness, and revolves around the dualism of good and evil. Best described to Star Wars fans: It’s kind of like the Force.

Prophet Mani was born in the northern region of Parthian-controlled Babylonia on April 14, 216 CE. He received his first divine revelation as a child, being contacted and taught by a spirit which he referred to as “Twin.” This spirit or apparition allegedly visited him again 12 years later, while he was in his early- to mid-twenties, and informed him that it was his destiny to preach the truths he had received to the world.

Upon receiving his divine revelations, the young prophet informed his family of his spiritual insights before heading out on a series of missionary escapades, the first of which was to the Indian subcontinent. Mani experienced considerable success, earning the patronage of some of the major power players in the Sasanian Empire, including King Shapur I. In the 4th century, Manichaeism reached its peak in the Western world, with temples across Roman Empire and as far west as South Gaul (France) and Spain.

Unfortunately, like many people who have claimed to possess divine knowledge throughout history — from John the Baptist and Jesus Christ to modern-day preachers like David Koresh of the Branch Davidians sect — Mani’s fate would be untimely death. Sometime in 277 CE, according to Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia of World Religions, Mani was imprisoned by King Bahram I at the behest of Zoroastrian priests; he died in captivity 26 days later.

Mani of Cao’an

Manichaeism in the Middle Kingdom

Mani himself once (allegedly) stated: “My religion is of that kind that it will be manifest in every country and in all languages and it will be taught in faraway countries.” It turns out he wasn’t wrong.

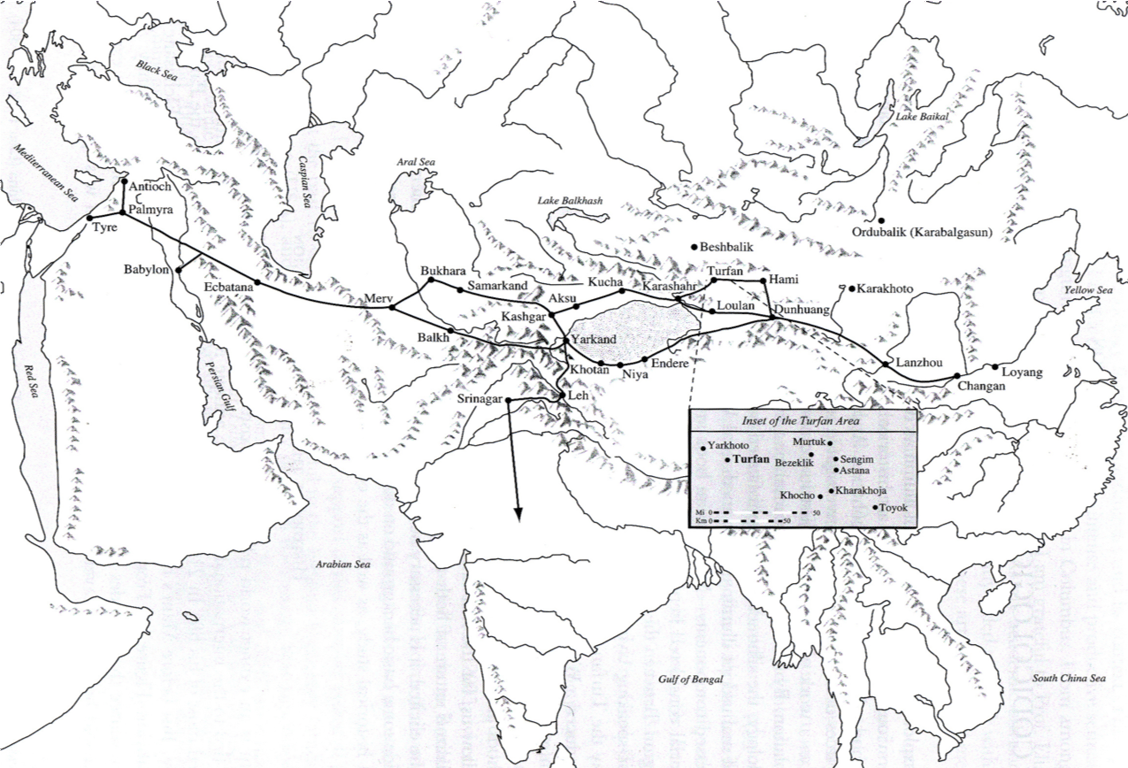

While Mani met with an untimely end, his faith, for a time, prospered. During his later life and in the centuries following his death, Manichaeism spread in North Africa, Central Asia, throughout the Roman Empire and, eventually, into China: from present-day Xinjiang and North China to as far south as Fujian.

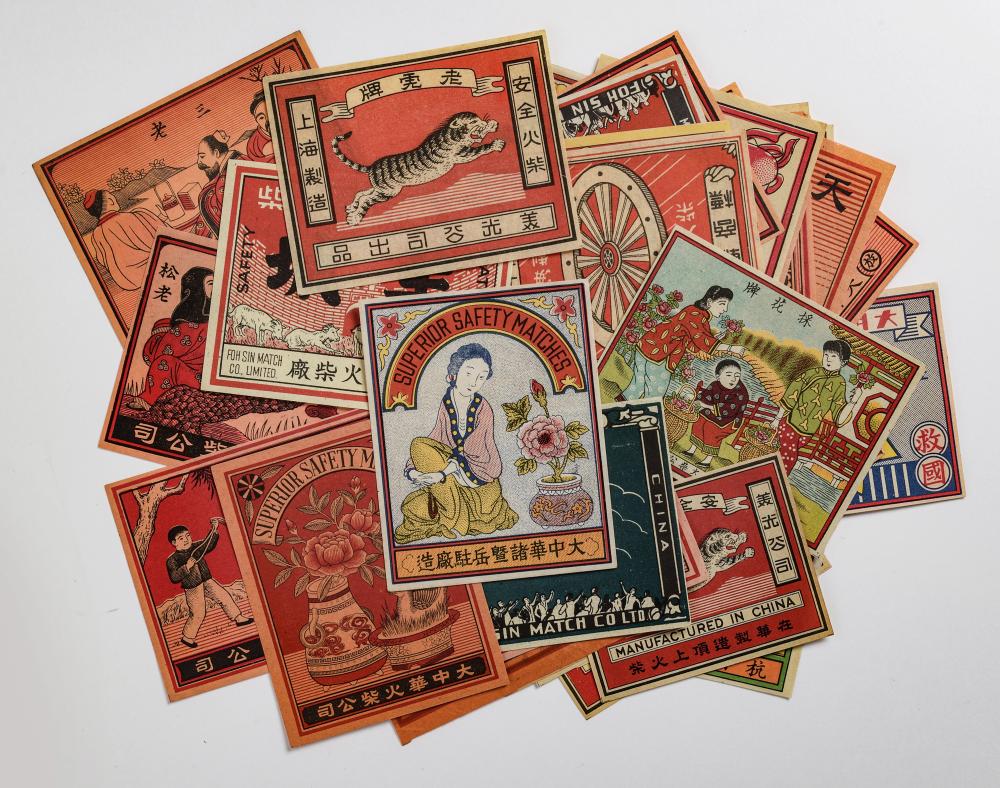

Manichaeism arrived in China in the 6th and 7th centuries CE, during the Tang Dynasty, from Central Asia. The faith, known in China as Mingjiao (明教) or Monijiao (摩尼教), found followers among the Uyghur Khaganate, an empire that spanned what is now modern-day China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Mongolia, from the mid-8th century to the mid-9th century. From there, it made its way into West and then North China.

The spread of Manichaeism along the Silk Road

“The more ‘classical’ Chinese Manichaeism with strong links to Central Asia would have been practiced mainly in cities of North China, including Chang’an, Luoyang, Taiyuan and Dunhuang,” Dr Gunner Mikkelsen, a Manichaeism expert and senior lecturer at Macquarie University, Sydney, tells RADII. “After the fall of the Uyghur steppe empire, Manichaeism in, it appears, fairly ‘classical’ form was practiced by Uyghurs at Turfan [West Uyghur Kingdom].”

But Mani’s faith would not be restricted to China’s northern reaches indefinitely — it eventually spread south to the present-day provinces of Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Hubei and, of course, Fujian, the latter of which it reached in the 9th century.

When Manichaeism arrived in China, the religion scene was somewhat crowded, with Confucianism, Buddhism and Daoism already well established. Still, the faith gained ground, possibly due to its syncretism of Buddhist and Daoist elements.

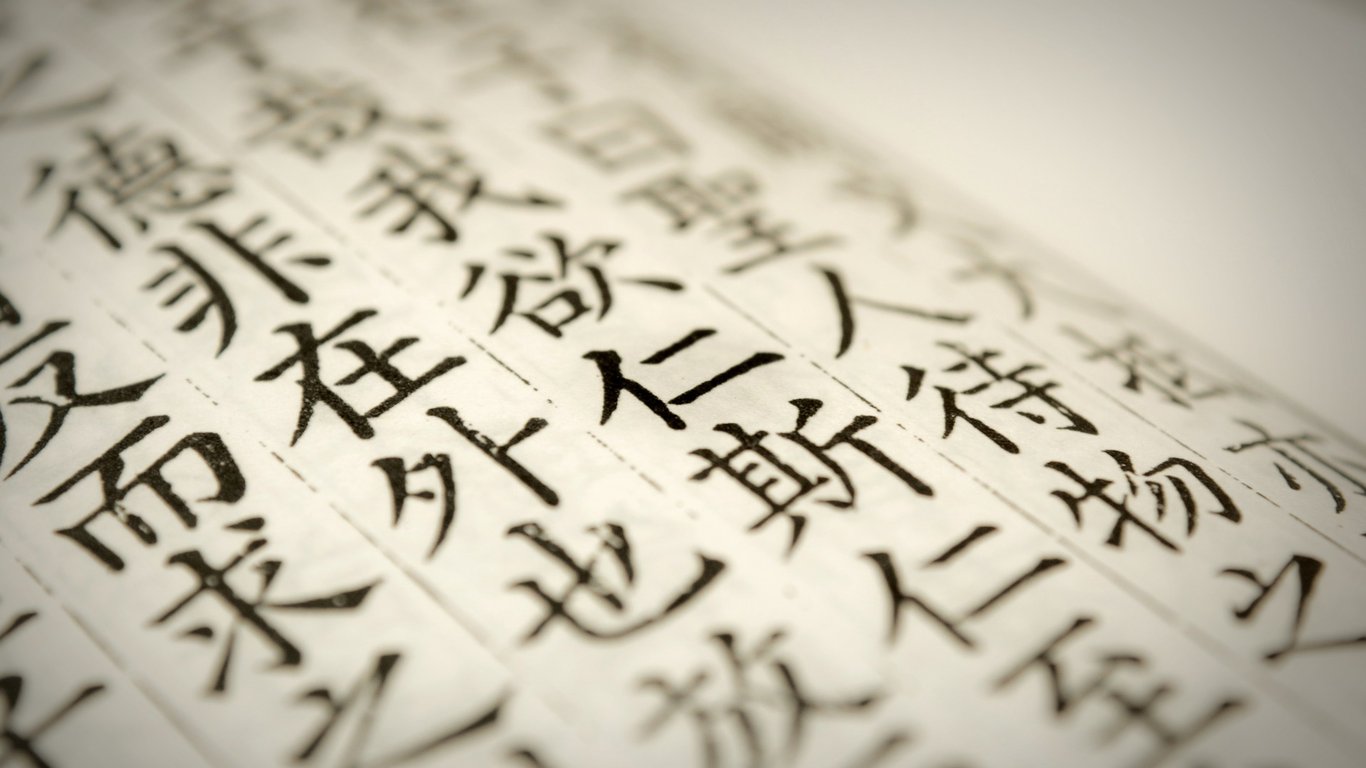

“Most of the Chinese Manichaean texts from Dunhuang and the Turfan region are translated from originals in Parthian and other languages. They date to the Tang Dynasty. Buddhist textual formats, language and technical terminology are employed, and they are more verbose (especially with the added Buddhist contents),” writes Mikkelsen, adding that the texts appear to be largely faithful to their source material.

Interestingly, it appears that Mani’s faith not only blended and took inspiration from established Chinese belief systems, but also impacted local beliefs. According to Mikkelsen, texts discovered in Fujian’s Xiapu county from the Song Dynasty or later include Manichaean elements, but are not necessarily from a community of Manichaeans.

You might also like:

“Chinese People Forgot Their Own Culture”: Why Confucian Education is Making a ComebackSupporters of this controversial trend, which emphasizes reciting classic texts, feel that China abandoned “authentic” culture during 20th century reformsArticle Nov 26, 2019

“Chinese People Forgot Their Own Culture”: Why Confucian Education is Making a ComebackSupporters of this controversial trend, which emphasizes reciting classic texts, feel that China abandoned “authentic” culture during 20th century reformsArticle Nov 26, 2019

“The Xiapu texts contain plenty of Manichaean elements, but the community to whom the texts belonged appears not to be Manichaean per se,” Mikkelsen tells RADII. “It has recently been suggested that the texts belonged to the syncretic Lingyuan (靈源) folk religion, which flourished in Fujian during the Ming and Qing dynasties. The whole question is being researched.”

The Last House of Mani

Tucked away in a small depression near the base of the Huabiao Foothills sits the temple of Cao’an (草庵), literally translated as “thatched nunnery” in English. Surrounded by verdant forest and situated next to a primary school, the temple grounds are an unassuming site, and one would be forgiven for disinterestedly wandering past the entrance.

When I first visit the Cao’an, it is New Year’s Day, and throngs of visitors are wandering the temple grounds snapping photos and burning incense.

Among the first things one encounters when entering the site is a deep, circular hole in the ground, accompanied by a nearby sign explaining that a black-glazed bowl adorned with Chinese characters tying it to Mani’s faith was found there back in 1979. Across from the hole is a thousand-year-old tree.

The temple itself is set on top of a massive moon-shaped rock and is quite small for a site of such historical significance, proof that size doesn’t always matter. Inside Cao’an’s small and well-kept main hall is the main attraction: Mani, also known as the “Buddha of Light,” carved into the side of a massive slab of stone.

A sign at the site claims the statue was carved in 1339, a fact further attested to by a Buddhist nun I speak to during my visit to Cao’an. The sign further states, verbatim: “As the world’s only extant stone statue of the founder of Manichaeism, it is valuable evidence to witness the spread of Manichaeism in ancient China and bears an important testimony to inclusive and multicultural traditions on [sic] Quanzhou during the Song and Yuan dynasties.” (Interestingly, Mikkelsen notes that there is at least one other building still standing in Fujian that may have been a Manichaean temple, although no solid evidence to support this has been put forward.)

Stoic, peaceful and unquestionably Buddha-like, Cao’an’s Mani is a sight to behold. Unlike most Buddha statues, though, there are several key differences when looking at Mani.

For one, his gaze is focused directly on worshippers, as opposed to downward, a commonality among statues of the founder of Buddhism. Additionally, the statue has long, chest-length hair and a beard fashioned into two “spikes” — neither of which are features associated with the Buddha.

“I don’t have an immediate impression of Mani in this sculpture. I can understand the localization [of Mani’s features] by the artist that carved it, using his own imagination,” Shaw Xu, a Shanghai-based architect visiting the site, tells me. “I wanted to check this place out and learn more about it, because it is kind of lost and marginalized historically.”

You might also like:

China’s Struggles to Reconcile Church and State are Rooted in HistoryThe Chinese State is cracking down on global religions, but why?Article Jan 29, 2019

China’s Struggles to Reconcile Church and State are Rooted in HistoryThe Chinese State is cracking down on global religions, but why?Article Jan 29, 2019

While Xu may be overstating the extent to which Chinese Manichaeism has been historically sidelined (as previously mentioned, there is a slew of academic work on the subject), he’s not entirely wrong: ask your nearest Chinese colleague, friend or family member if they are familiar with Chinese Manichaeism, and chances are they will have zero idea what you are talking about. Manichaeism is kind of lost, and it’s fair to state that the religion has been forgotten in the Chinese public’s collective memory.

Curious as to whether any followers of Mani still practice the ancient faith at the temple, I ask a Buddhist nun who works as a caretaker at the site if people visiting the temple today have a relationship with or understanding of the religion that resulted in the 680-year-old relief. “Buddhists are the ones who take care of the temple, and they are the ones who visit it now, although many people also come here to see the statue of Mani, out of curiosity,” she tells me.

Curiosity is one thing, though, and faith is an entirely different thing. While I leave Cao’an with the knowledge that the Mani carving there is likely the last on the planet, I’m left wondering: Are there are any Manichees left?

Snuffed Out

Cao’an was originally constructed sometime from 1131-1162 CE, according to signage posted at the temple, during the Shaoxing reign of the Southern Song Dynasty. At this time, the faith founded by Prophet Mani was largely — if not completely — gone in the Western world.

A series of aggressive anti-Manichaean policies ultimately led to the fall of Mani’s religion in the West, while policies of persecution by Zoroastrian and later Muslim dogmatists helped stomp out the faith in its place of birth, Mesopotamia. According to Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia of World Religions, the faith had almost entirely disappeared from western Europe by the conclusion of the 5th century. It was essentially eradicated in the Eastern Roman Empire during the 6th century.

You might also like:

Fuzhou to Host 2020 UNESCO World Heritage Committee as China Overtakes Italy for Most Listed Sites29 new sites were added to UNESCO’s World Heritage Site list last weekend, including two in ChinaArticle Jul 15, 2019

Fuzhou to Host 2020 UNESCO World Heritage Committee as China Overtakes Italy for Most Listed Sites29 new sites were added to UNESCO’s World Heritage Site list last weekend, including two in ChinaArticle Jul 15, 2019

“Persecution was a major factor contributing to the demise of Manichaeism. Manichaeans were persecuted in the Roman world, in Persia and in China. The reasons for the persecution were many — religious, political, economic,” states Mikkelsen. “The rise of Islam was a factor, too, and so was the fall of the Uyghur steppe empire in the mid-9th century. The Uyghurs supported and practiced Manichaeism in their empire and in China.”

In China, Manichees got a solid dose of persecution during the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution of the Tang Dynasty, under Emperor Wuzong. The campaign against Buddhism, in addition to foreign faiths such as Manichaeism, reached a fever pitch in 845 CE, when monasteries were banned and religious items in bronze, silver or gold were ordered to be handed over to authorities.

“The persecution instigated by Tang Wuzong was directed towards most foreign religions, including Manichaeism, but Buddhism in particular. It is probable that Manichaeans were persecuted because they resembled Buddhists, their texts were heavily Buddhisized, and Mani was a Buddha of Light,” according to Mikkelsen. “It is probable that they were persecuted because of the demise of the Uyghurs, their protectors. Tang-Uyghur relations were strained.”

In Fujian, though, the faith of Persian preacher Mani was still around, in some form or another, at least another 500 years after the religious purge. But what about today, 680 years on from the carving of the Buddha of Light at Cao’an? Are the last of Mani’s followers still residing in the lands surrounding the temple?

In our correspondence, Mikkelsen suggests that, while local people come to the temple to honor the Buddha of Light, most have no idea who he is, killing the idea that Manichees still reside in the area.

“Some locals visit the temple, pay their respect to the Mani Light-Buddha, burn incense, etcetera, and there is or was an annual event at the temple,” he says. “I doubt that these locals generally link this Mani to Mani, the founder of Manichaeism.”

This echoes what the Buddhist nun at the site tells me: that, for all intents and purposes, the Cao’an of today is a site used by practitioners of the Buddhist faith.

And that’s the crux of it: China is home to what is arguably the last Manichaean temple on Earth, a religious place easily accessible by southern cities via high-speed rail. Unfortunately for cultural cosmonauts, it turns out that modern-day followers of the “Religion of Light” are slightly more elusive.