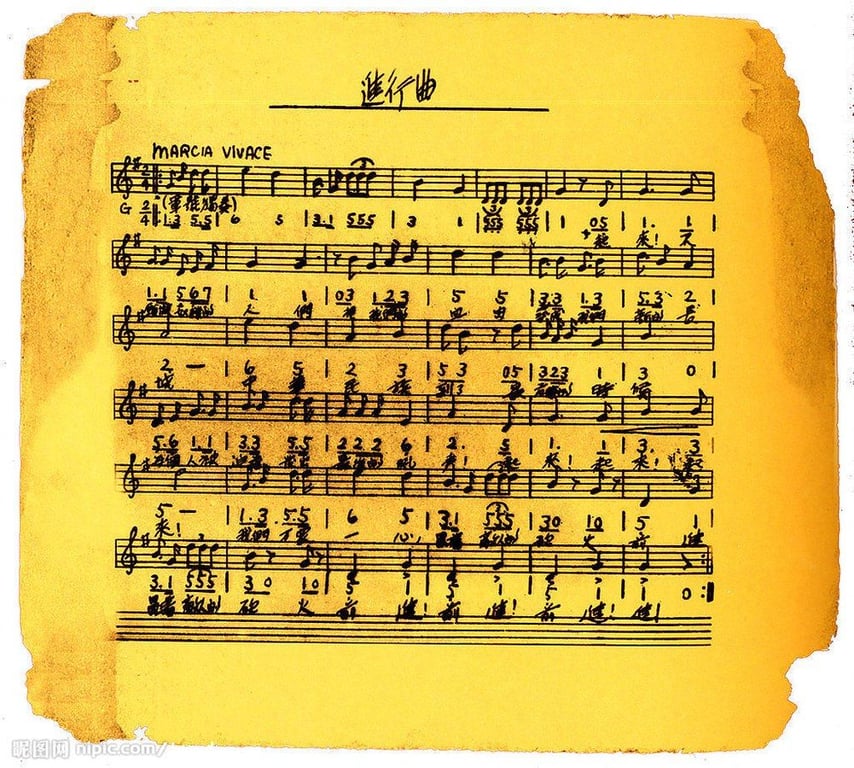

David Bandurski published a gem of a read on Quartz over the weekend, “There’s an American story at the heart of China’s national anthem,” which examines the (relatively brief) history of the Chinese national anthem, “March of the Volunteers.” The song was hand-written in 1935 by Tie Er, popularized the year after by a Chinese subsidiary of a French record company in Shanghai, fell out of favor during the Cultural Revolution, and only in 1982 officially designated as the country’s national anthem (then made constitutional in 2004).

It’s all very timely, as March of the Volunteers made headlines recently after China’s top legislature proposed a draft law to protect its sanctity, including up to 15 days detention for those who have “maliciously modified the lyrics or performed it in a distorted or disrespectful way.” One lawmaker went so far as asking Chinese people to stop using the “American” gesture of placing a hand over the heart during the national anthem.

But the song’s early years had some very compelling American tie-ins, as we learn from Bandurski:

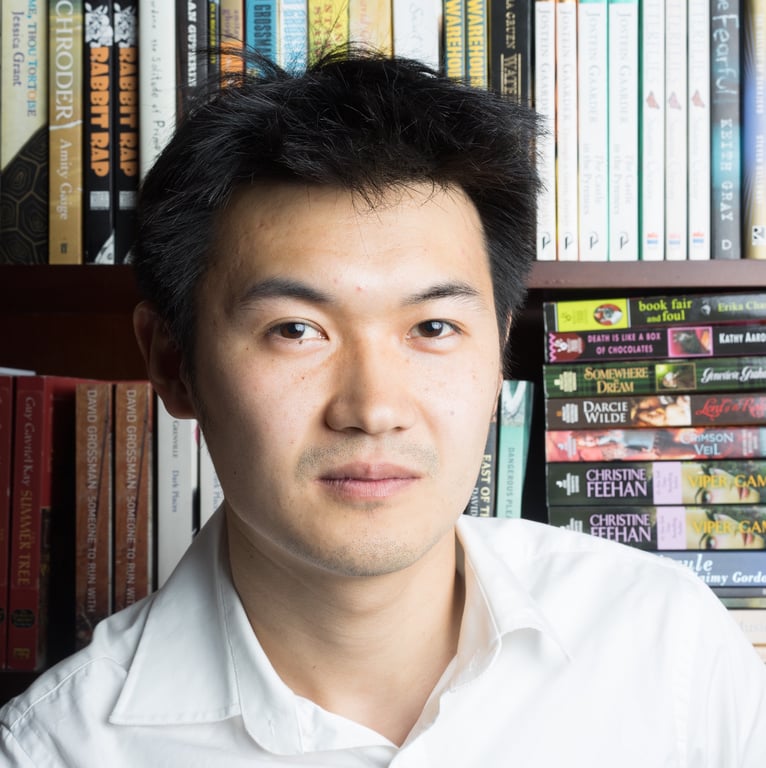

In 1940, the year after the release of The 400 Million, Liu Liangmo [a Chinese intellectual and activist employed by the YMCA in Shanghai] too left China for the United States, carrying Chinese songs of resistance along. Liu had been invited to New York by the YMCA for further study(link in Chinese), but was soon visiting cities and small towns across the country, raising awareness about China’s war of resistance against the invading Japanese army. Ten years later, writing in New York’s left-leaning China Daily News, a Chinese-language newspaper, Liu would recall his mission at the time, and how it brought him face-to-face with one of the great American voices of the day, Paul Leroy Robeson, a former professional athlete and graduate of Columbia Law School who by the 1930s had become an international singing sensation, a cinema star, and a leading voice for civil rights.

Paul Robeson, an American icon who fought for individual liberty at home and abroad, and who was persecuted during the McCarthy era for his outspoken beliefs, performed a stirring rendition of March of the Volunteers in 1940 at a massive recital in West Harlem. The year after, Robeson recorded his rendition of the song, which he called “Chee Lai” — an Americanized spelling of the first two Chinese characters in the song, qilai, which taken together is March of the Volunteers’ sonorous, urgent call to “Arise”:

Play the video above, in which Robeson says, “This is a song born in the struggle of the brave Chinese people,” before singing in (very good) Mandarin Chinese:

Arise, ye who refuse to be slaves!

With our flesh and blood, let us build a new Great Wall!

As China faces its greatest peril

From each one the urgent call to action comes forth.

Arise! Arise! Arise!

Millions of but one heart

Braving the enemies’ fire! March on!

Braving the enemies’ fire! March on!

March on! March, march on!

Then he does a version in English, substituting the second, third, and fourth lines (which he sang in the original Chinese) to:

Let’s stand up and fight for liberty and true democracy!

All our world is facing the chain of the tyrants,

Everyone who works for freedom is now crying,

Arise…

It’s a classic in the political folk music genre — if not slightly forgotten in our day and age.

After Robeson’s death in 1976, none other than China’s People’s Daily wrote:

In the period of the Chinese people’s war of resistance, he sang “March of the Volunteers” in the Chinese tongue, and supported the war of the Chinese people against the Japanese, becoming a true friend to the people of our nation.

There’s an American story at the heart of China’s national anthem [Quartz]