Photosensitive is a monthly RADII column that focuses on Chinese photographers who are documenting trends, youth, and society in modern China.

Born in Lishui, a small town in China’s Zhejiang province, photojournalist turned art photographer Chen Ronghui initially found himself drawn to the medium of photography at a young age.

“The first time I picked up a camera was in high school,” he recalls. “The local government had just built a photography museum — the first of its kind in the country — and I still remember the otherworldly feeling of looking through a viewfinder for the first time.”

“Modern Shanghai & Runaway World” (2015 & 2019)

In the beginning, Chen’s desire was to pursue the intersection of photography and journalism. “I wanted to follow in [famed American photojournalist] W. Eugene Smith’s footsteps,” he says, “and spend my life documenting the country’s social problems.”

His photojournalistic work, which investigates the individual within developing China, has been covered by the likes of National Geographic, New York Times and Time Magazine. He also previously worked for Sixth Tone as the head of the news outlet’s visual department.

“Modern Shanghai & Runaway World” (2015 & 2019)

Along the line, however, Chen had a change of heart. He explains the circumstances behind him discovering that his fate lay with art photography, rather than photojournalism. “I hit a turning point in 2015, when Rongrong, the co-founder of the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre in Beijing, commented on my work as part of the Jimei-Arles Portfolio Review. He challenged me to do more than just document a story, saying that I should control the frame in ways that would reflect my own personal perspective.”

This led Chen to study the works of famed photographers Walker Evans, Diane Arbus, Alec Soth, and Gregory Crewdson in search of inspiration. It led him to realize that photojournalism was, in fact, not his passion.

“Freezing Land” (2016-2019)

This change of focus brought with it an evolution of his art and the way he views photography. While he admits that photography is always changing, as with any art, he says, “When I was a photojournalist, I felt that news content was more important to some extent. But now, I pay more attention to photography language, and I think a good photography language itself contains good content.”

That epiphany led him to leaving China, however temporarily, to take up a graduate course at Yale University. He saw his life there as considerably different than in China, evident in the works in his “An Ordinary Evening in New Haven” series. Fearful of the spate of crime happening in the city, and conscious of carrying an expensive camera with him, Chen says that for his first year living there, “every night I ran home.”

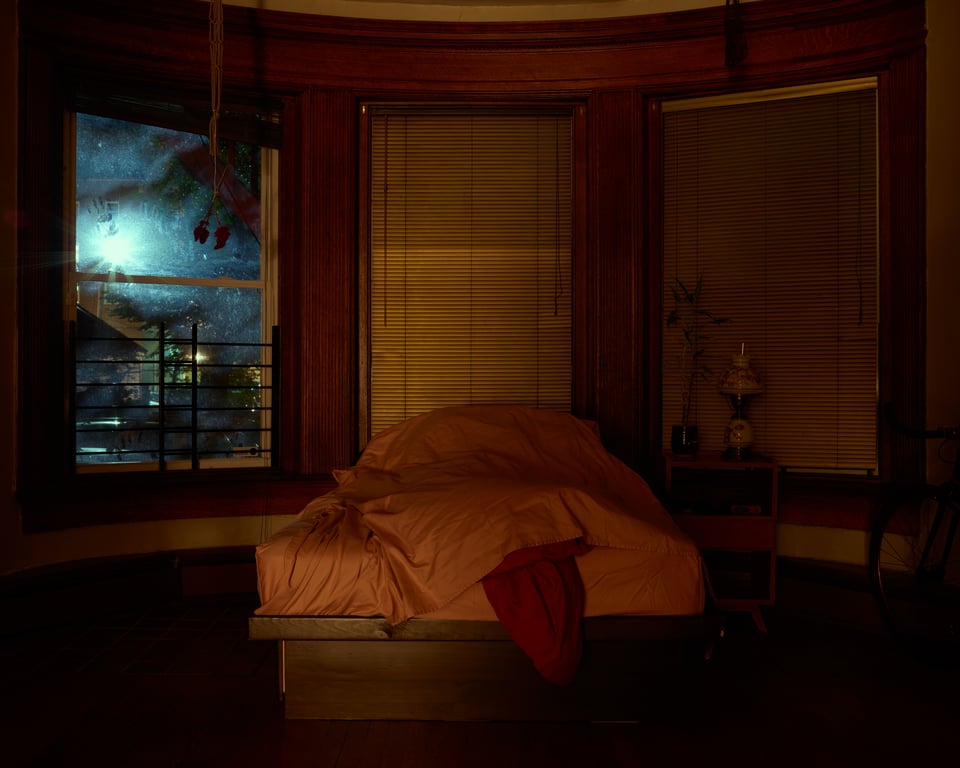

“An Ordinary Evening in New Haven” (2019)

“When I got back, I often had no time to turn on the lights,” he recalls. “I just lay on the sofa and watched the light coming in — which reminded me of my childhood.

“I lived in a rural area in China with my grandparents. They never turned on the lights at night to save on electricity. As a boy full of curiosity, I wanted to catch the light and beauty at night, like fireflies and stars. So I used the long-exposure to capture these lights of glow. I wanted to document the beauty and mystery in the home.”

“An Ordinary Evening in New Haven” (2019)

His heart remains in China, though, something that is obvious while he talks around socioeconomic issues that the country faces. His work documenting pollution crises along the Yangtze River from 2013, for example, saw him traverse thousands of miles to document how China’s longest river has become the site of a number of “cancer towns,” brought on by the “chemical plants standing mere hundreds of meters away from residential districts — with no obvious barriers between them.”

“Petrochemical China” (2013-2015)

One of his more recent works, “Freezing Land,” takes on a more personal view, as it documents the hardships of life in China’s historically poorer northeastern regions. Chen travelled through five cities in the region from 2016 to 2019, capturing lives in towns such as Yichun in Heilongjiang province, Fushun in Liaoning province and Longjing in Jilin province. The project began in December of 2016, and saw Chen return to the region during the winter months over the following years.

The project is a fascinating investigation of young people based in the region, turning the lens on those on the verge of moving away for work or to study at university. Chen chose to focus specifically on young people for this reason, teasing out the anxieties of life in these border towns.

“Freezing Land” (2016-2019)

Chen says about the project:

“During this process, the emotion expressed by these young people — a mixed sense of hesitation, loneliness, and hope — resonated with me.”

Desolation is a tangible theme in this series — a mixture of harsh and snowy landscapes juxtaposed with images of young adults smoking cigarettes in the wintry outdoors, a boy standing over a pile of empty green beer bottles, and another young male dressed in women’s clothes and holding a black wig against his knee.

“Freezing Land” (2016-2019)

Yet the actors that populate this work stand in stark contrast to one another, offering a variety of human stories within this largely overlooked region of the country.

“This [series] made me realize that I’m not just photographing the lost ‘Chinese Dream’ on this freezing northeastern land,” he says, “but also the uncertainty we young people, as individuals, are facing under today’s collectivism in China.

“At this moment, I pressed the shutter.”

All images: courtesy Chen Ronghui