The Chinese language is largely genderless; nouns aren’t associated with any gender, and once upon a time, the same third-person pronouns were applied across gender, such as qí 其, zhī 之 or more modernly, tā 他. But that changed in the early 20th century.

When the New Culture Movement took place in China in the 1910s and 1920s, scholars were translating literature into Chinese to promote the incorporation of Western ideals like democracy and science into Chinese culture. But these scholars found it difficult to translate she/her into Chinese. Thus, tā 她 was created using the female radical 女 (a radical is a basic graphical component of a Chinese character that imparts linguistic meaning). The invention was met with some initial backlash, but gradually it has become widely accepted as part of the standardized written Mandarin system.

As the world incorporates gender-neutral and gender-inclusive pronouns, such as “they/them” or “ze/zir” in English, Chinese queers and gender activists have also been advocating for more gender-friendly Chinese pronouns.

Who Uses X也 And TA?

Instead of the female radical tā, in 2015, an intersex information platform called The Missing Gender 0.972 suggested using the English letter X as a genderfluid radical to create a new pronoun: X也.

Since HK protests I’ve been thinking about newly invented characters & how they can go from art to text you can type out.

X也 is one of those characters that I feel like should get fast tracked to being added to text entry, but there are so many barriers. https://t.co/kJSNpi5omM

— Frankie Huang 黄秋隐 (@ourobororoboruo) November 17, 2020

Another example of new pronouns commonly used in mainland China is the pinyin romanization TA, sidestepping the now masculine 他, with the human radical, and 她, both pronounced as tā.

“Some genderfluid, genderqueer or nonbinary people use TA, and Chinese queer and feminist online communities seem more comfortable with this usage than mainstream media, both when speaking about a generic or anonymous third person and when speaking about a nonbinary individual,” Jinghua Qian, an Australia-based writer, replies via email, who goes by ey/eir/em or they/their/them in English, yi 伊 in Shanghainese or TA in Mandarin.

article on the resurgence of gender-inclusive pronouns in written chinese (afaik spoken pronouns are already gender-inclusive in most chinese languages). the new coinage X也 looks hot but i prefer 伊 which is the standard 3rd-per pronoun in shanghainese https://t.co/C2PmeZoXES

— Jinghua Qian (@qianjinghua) November 18, 2020

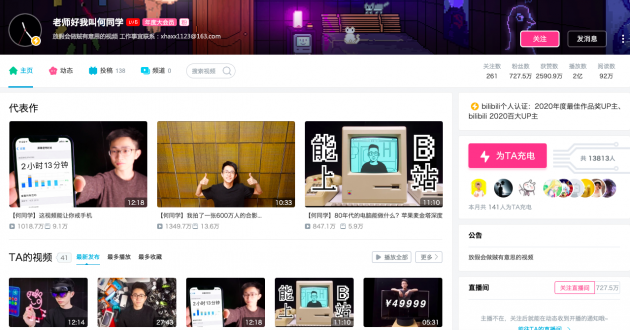

Qian also notices that “TA” has become more mainstream for younger generations beyond Chinese queer and transgender circles. For example, Chinese streaming platform Bilibili uses “Videos of TA” rather than “His/Her Videos” on each creator’s homepage.

Screenshot from tech video creator He Tongxue’s homepage on Bilibili

Though mainstream outlets like CCTV also use TA when referring to a person whose gender remains unknown or irrelevant in context, it seems more accidental than a conscious choice to Lilian Shen (she/her/她), a co-founder of Queer Talks, a biweekly bilingual discussion-based event for LGBTQIA+ individuals.

CCTV used TA on Chinese social media platform Weibo. (Image from Weibo)

“Gender binary trans like Jin Xing are a bit easier for mainstream media to conceptualize because they still go by he or she,” Shen says via voice messages. “Even if people are aware of trans folks and want to use the correct pronouns, they are more likely to use he or she instead of TA.”

Related:

How Transgender Dancer Jin Xing Became A Chinese Icon“There is only one Jin Xing, and Jin Xing’s success cannot be replicated”Article Jun 10, 2021

How Transgender Dancer Jin Xing Became A Chinese Icon“There is only one Jin Xing, and Jin Xing’s success cannot be replicated”Article Jun 10, 2021

Pronouns and Visibility

“I think pronouns actually provide an opportunity to show trans exist,” says Xiao (she/TA), a trans woman and gender studies graduate student in the U.S. TA says via text that correct pronouns are very important for people who disagree with their assigned genders or are frequently misidentified.

Xiao hates being mistaken as he and appreciates being asked preferred pronouns during first encounters. TA recalls an incident where pronouns were not included in a self-introduction in a gender group where TA volunteered.

“At that time, I felt I was discouraged from showing up as a trans,” Xiao says.

Another gender studies scholar Alexwood (she/her/她) explains via voice message that the use of gender pronouns is not only an expression of gender identity but also a political statement. “Ideologically, we are showing resistance and challenging the binary gender system.”

“[Preferred pronoun] is a crucial part of their entire identity construction.”

— Alexwood

Related:

This Video Challenging Gender Stereotypes Went Viral for Women’s Day“We ask females how to balance family and career. But we never ask men the same question”Article Mar 09, 2021

This Video Challenging Gender Stereotypes Went Viral for Women’s Day“We ask females how to balance family and career. But we never ask men the same question”Article Mar 09, 2021

Labels are Limiting

Yang Yinyan, the founder of Xi’an Relax LBT Center, grew up hating having to fill out the gender column in any form. Yang doesn’t like any pronouns and prefers to be called by name.

“Neither is me. I’m both a male and female, I have both characteristics and personalities, I don’t belong to either one,” Yang says, adding that it’s not easy to type TA or X也 on Chinese keyboards. “It’s too inconvenient to switch between Chinese and English input methods in order to type them out. I only use TA when I write official reports. I don’t like to use it on a daily basis.”

Instead, Yang continues using 他, unless the person referred to has a preference, arguing that it’s not a male radical but a human radical.

“It’s ok, we don’t need to differentiate genders. We’re all human.”

— Yang Yinyan

Related:

Queer East Film Festival Finds a Global Audience for Asian LGBTQ+ Stories Amid Covid-19The pandemic forced Queer East Film Festival online, but there, they found a larger, globally-based audienceArticle Aug 12, 2020

Queer East Film Festival Finds a Global Audience for Asian LGBTQ+ Stories Amid Covid-19The pandemic forced Queer East Film Festival online, but there, they found a larger, globally-based audienceArticle Aug 12, 2020

Yang also notices that very few people in the community use gender-neutral pronouns. Some are genderfluid just like Yang, some stopped bothering with it after they pass a certain stage of identity crises, some just haven’t found the best language.

“It makes them feel uncomfortable anyway, so they were like ‘whatever,’” Yang explains.

More importantly, as Qian points out, pronouns make less of a difference in Chinese than in English because 他 and 她 have the same pronunciation in speech.

“In the Chinese languages I speak (Shanghainese and Mandarin), pronouns are already gender-inclusive by default, they’re only gendered in written text and even then it’s kind of subtle, so it makes sense to me that trans communities in China are less preoccupied with pronouns compared to English speakers,” Qian says in the email.

“There are so many other issues that are a higher priority for trans people everywhere, such as access to healthcare and education and protection from discrimination, violence and abuse,” says Qian.

What’s Next?

All the same, most activists believe that establishing proper pronouns can be a good start to addressing some gender issues.

“We should use more gender-friendly pronouns, not just because of trans or queers. I think the use and mindset of binary pronouns hurt everyone. Because gender itself is a fictitious concept,” Shen says.

“Gender-neutral pronouns such as TA make us not need to define others, their identity and expression are their business.”

— Lilian Shen

She has noticed that some customer services on Chinese biggest online shopping platform Taobao have started to use TA to address customers. Shen is unsure if it’s a gender-aware approach but thinks it’s a promising sign.

In another instance, Yang also felt respected when cashiers at clothing store Uniqlo began addressing shoppers as guest, instead of using sir or ma’am.

“I hope that one day the entire society will abandon gender pronouns and only refer to people based on the role they play in certain circumstances,” Yang says.

At the very least, the hope is that gender-neutral pronouns will become more mainstream. Queer director Da Jing (他/TA/they) says that they believe new genderless Chinese pronouns will appear in the future as sex and gender education gradually improve in China.

Jing says, “from my observation, queers who were born after 2000 place great emphasis on individualism, independent thinking, and self-realization. So I am very optimistic that queer culture will completely break the traditional Chinese binary gender education and become the mainstream.”

Cover image designed by Sabina Islas