After student Luo Xixi accused her PhD supervisor Chen Xiaowu of sexual harassment on New Year’s Day, the #MeToo movement in China set universities ablaze.

Former Peking University and Nanjing University professor Shen Yang, Sun Yat-sen University professor Zhang Peng, Communication University of China professor Xie Luncan, and more have been accused of years of sexual harassment by several former students. The schools have announced they will investigate and fire them if found guilty of sexual misconduct.

Now, China’s #MeToo movement is spreading into other sectors. Despite repeated obstacles and attempted suppression, there’s a real feeling that — thanks to some extremely brave individuals — #MeToo is not going to go away in China.

Related:

Why is #MeToo Different in China?Article Jan 24, 2018

Why is #MeToo Different in China?Article Jan 24, 2018

Over the past week, at least ten activists from non-profit organizations, along with former journalists and current public intellectuals, have been accused of sexual harassment or assault by anonymous letters published online or on WeChat Moments.

These included Lei Chuang, the founder of Yiyou Charity, which works to counter public discrimination against HBV carriers; the founder of Nature University, an environment protection learning platform Feng Yongfeng; and the founder of Rainbow China, HIV/AIDS and LGBT activist Zhang Jinxiong. All three admitted wrongdoing and apologized to the victims publicly. Lei Chuang resigned from the organization and attempted to clarify that he and the victim “were in a relationship” (something the victim subsequently disputed); Feng Yongfeng promised he would quit drinking and never let it happen again; Zhang Jinxiong is back to work praying to God.

The accusations centering on intellectuals started with one against Yuan Tianpeng, the only Chinese member of the American National Association of Parliamentarians who has been conducting training for democratic negotiation rules in the non-profit sector.

Chinese media was the next sector to be rocked by allegations after Zhang Wen, veteran political commentator and former editor-in-chief of Oriental Outlook and Xinhuanet’s Global Biweekly, author of three books, and advocator of democracy, was accused of a rape committed on May 15. The accusation drew significant attention and public outrage.

Related:

Wǒ Men Podcast: Let’s Talk About Sexual ConsentArticle May 28, 2018

Wǒ Men Podcast: Let’s Talk About Sexual ConsentArticle May 28, 2018

A long letter “Zhang Wen, Stop Your Assault!” written by a 27-year-old legal worker under the pseudonym 小精灵 Little Spirit went viral on Weibo on July 25, in which she described how Zhang Wen raped her at his teahouse after she got drunk, then threatened her to keep it secret via messages. According to the letter, Zhang Wen also bragged about his network in journalism circles and that he has had sexual intercourse with more than 100 girls, most of whom are his interns or new recruits.

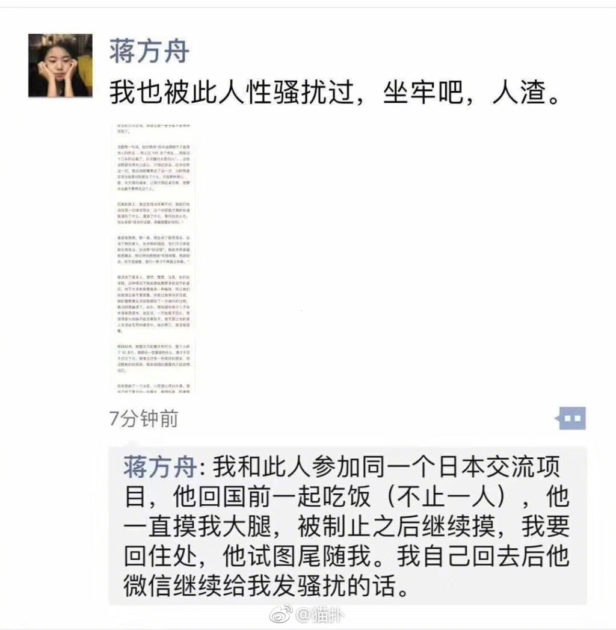

Shortly afterwards, two more women accused Zhang Wen of sexual assault in an article of The Paper. In the following days, Jiang Fangzhou, vice editor in chief of New Weekly and a famous writer with 7.6 million followers on Weibo, together with sports journalist Yi Xiaohe and artist Wang Yanyun all stood up and accused Zhang Wen of sexual harassment.

Jiang Fangzhou’s accusation on WeChat Moments

Zhang Wen’s response was to attempt “slut-shaming”, saying “Jiang is single and has had many boyfriends before” and “Yi is divorced, and frequently goes to parties.” He then refused to comment further in a video call with The Beijing News.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

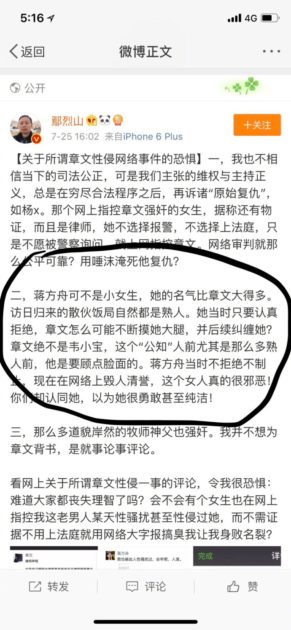

Moreover, male writers such as Yan Lieshan supported Zhang, questioning why Jiang didn’t resist or speak up when Wen was touching her legs under the table, because Jiang “is a lot more famous than Zhang Wen.” The post included the line, “this woman is evil!”

Yan Lieshan’s post

A common thread among many of the male responses was to question why the victims had not sort help from the police or taken their cases to the judicial system. Despite the potential for trauma, Little Spirit decided to report her case. In a public letter posted to WeChat, she wrote about the difficulty of speaking out, but also how she had learned to change her mentality and realize that she had done nothing wrong.

We don’t know how this case will end yet, but what we have seen is that a deep interview with Little Spirit on The Portrait was taken down on WeChat, and an article on newspaper Southern Weekly focused on the allegations can no longer be seen either on Weibo nor the original website.

A commentator Chen Di said on Weibo argued that the emergence of so many allegations in the non-profit and education sectors was not necessarily because assault was more prevalent in these areas, but that these sectors were more willing to support such accusations and investigate them properly: “This movement starting from universities and NPOs doesn’t mean that it’s the worst in those areas, but on the contrary, they are not the worst, so there is still enough healthy energy to support the resistance in the larger environment. What about others? Companies and state organs?”

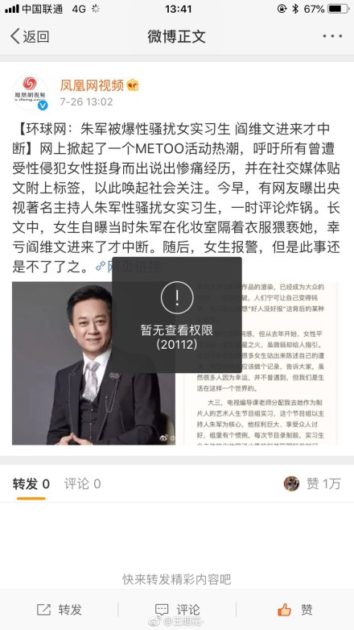

On June 26, Zhu Jun — one of the best-known CCTV personalities and presenter of the “billion-viewed” Spring Festival Gala for 21 years, as well as a host known for his “sentimental-style” of interview with A-list stars on talk show Artistic Life — was anonymously accused of sexual harassment by a former intern.

The familiar story of power-abuse and threats from the industry was treated differently however. Not only did Zhu’s accuser say that she was originally told to drop any complaints by the police because of Zhu and CCTV’s “positive influence on society”, but within a few hours of the Weibo post appearing, all reports containing “Zhu Jun sexual harassment,” including those from prominent news organizations ifeng.com and Caixin, were wiped out. Zhu Jun shut down all commenting on his own Weibo account shortly after.

An ifeng.com post on Weibo regarding allegations against Zhu Jun which was subsequently removed

Yet despite cover-ups and the fact that the Chinese language version of the MeToo hashtag remains blocked on Weibo, the movement is not letting up. Weibo users have found a number of inventive ways to keep the hashtag alive, translating it into a whole host of different languages and using rice (米 “mi”) and rabbit (兔 “tu”) emojis.

As a result, allegations keep finding a way into the public realm. One of the latest accusations came from a volunteer at China’s oldest music festival Midi Festival. On her sixth time volunteering at the self-styled “China’s Woodstock” near Taihu Lake in May 2017, the victim claims she was sexual assaulted by Zhou Yi, the director of Midi Kids, and subsequently suffered bipolar disorder, PTSD and depression for months.

She reached out to the principal and the founder of Midi Music School (established in 1993), Zhang Fan, for help, and hoped to see the abuser punished. According to Zhang Fan’s latest response, he arranged a meeting between the victim and the married abuser in February, suspended Zhou from working in April, and hoped to keep the issue private given that the two parties were in relationships.

The Weibo account 我是落生 (I Am Luosheng) which posted the victim’s testimony received a lawyer’s letter on Sunday from Zhou Yi accusing them of slander. In the meantime, a number of lawyers and KOLs on Weibo have shown their support for the victim.

The truth is yet to be found, but this wave of #MeToo in China is also sparking some necessary discussions related to sexual harassment.

Liu Yu, a political academic at Tsinghua University, expressed her doubts over the current “Big-Character-Poster-style” online movement, instead promoting the legal method for dealing with such claims and emphasizing the presumption of innocence for sexual accusations. Liu also argued that we should look at broader reasons for sexual abuse besides the individual mentality, such as pop culture’s impact on the objectification of women.

Lawyer Zhao Danmiao and commentator Bei Da Fei both contradicted Liu’s opinions with articles entitled “China’s #MeToo is Precious, Don’t Ruin it Easily” and “MeToo is not a conservative virginity movement or cultural revolution,” arguing that given the lack of a sound legal system, there is no more practical path than a social movement to increase society’s awareness of sexual harassment. It’s too early to talk about “rationale and boundaries” before some real change is made, they argued.

Meanwhile, Little Spirit told The Portrait: “I was inspired by #MeToo to step forward. I saw so many people like me, so I’m not afraid any more. I was raped, but it’s not my shame. It’s Zhang Wen’s.”

Hopefully this is just the start. The more people get involved into the discussion, the more we can improve conditions throughout the country, until the hardest wall is broken.

—

Cover image: A viral graphic on Weibo explaining 米兔

Related:

#MeToo Takes a Distinct Form in ChinaArticle Mar 10, 2018

#MeToo Takes a Distinct Form in ChinaArticle Mar 10, 2018

Wǒ Men Podcast: Let’s Talk About Sexual ConsentArticle May 28, 2018

Wǒ Men Podcast: Let’s Talk About Sexual ConsentArticle May 28, 2018