When I was young, I was fascinated by the sensation of my own pulse. I’d press my fingers into the flesh of my neck, or tenaciously probe the layer of baby fat that smothered the veins in my wrist, until I could feel its insistent rhythm against my fingertips. If I couldn’t find my pulse easily, I’d panic, convinced that I was moments from death, and search it out with increasing urgency. My pulse was incontrovertible proof of life; it was continuous, regular, independent of my thought. It spoke to me in a voice that was not my own. The first time a blood pressure cuff tightened against my arm, I feared that my pulse would be smothered.

Pulse-taking, or qiemai (切脉), is an essential diagnostic technique in Traditional Chinese Medicine. It’s one of the four examinations through which a TCM doctor arrives at a diagnosis: wang (望), or observation; wen (闻), or smelling and listening; wen (问), or asking (about a patient’s recent complaints and illness history); and qie (切), pulse-taking. Every TCM clinic I’ve visited is outfitted with a small pillow, often covered in brightly colored silk, that lies on the table in front of the patient’s chair. Some patients place their wrist on the pillow immediately upon sitting at the examination table, anticipating the pulse-reading before the examination has even begun; others obediently proffer one wrist, and then the other, at the doctor’s request.

In the TCM gynecology clinic, after the doctor has finished feeling the patient’s pulse, I occasionally give it a shot myself, gently placing my three middle fingers — index finger closest to the patient’s hand, always — onto the outer edge of her wrist. Here, though, I am not feeling simply for a reassuring beat, the sign of a living body, nor am I attempting to calibrate the pulse to the standard tick of a stopwatch. Instead, I am searching for subtle textures, minute qualities of the pulse that might vary along its length. I am feeling the movement of blood and qi (vital energy, “breath”) through the channels of the patient’s body.

This is a different pulse, an ordinary body speaking to me in an unfamiliar way. Each pulse descriptor, both poetic and precise, discloses details of the patient’s illness to the doctor.

Last Wednesday, one of the gynecologist’s graduate students thrust a patient’s wrist towards me. “Feel that!” she whispered, jolting me from a midmorning daze. “特别弦.” “Tebie xian.” The word 弦 xian literally means “bowstring.” This patient’s pulse was remarkably taut and stringlike, like a bowstring submerged beneath her flesh. Other patient’s pulses are sunken (沉脉 chenmai), sitting deeper in the wrist, or floating (浮脉 fumai), light and at the wrist’s surface, dissipating under pressure. Each descriptor (and there are many), both poetic and precise, discloses details of the patient’s illness to the doctor.

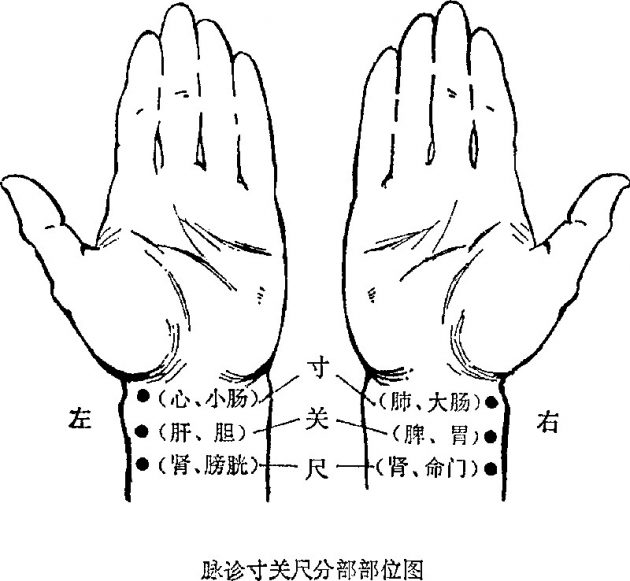

The placement of the pulse, its feel under each of my three fingertips, matters too. Each position (titled 寸 cun, 关 guan, and 尺 chi for each wrist) corresponds to a different organ, like the heart, or the kidneys, or the liver; the pulse at that location provides crucial information on the health of the body’s inner organs. There’s a lot of information dancing beneath my fingers. As Ted Kaptchuk describes in his book on TCM theory, The Web That Has No Weaver, a doctor whose touch is particularly acute — one who has accumulated years of practice feeling pulses, learning textures, speeds, and locations — might be able to make significant strides towards an incredibly accurate diagnosis simply by feeling a patient’s wrist.

This way of feeling the pulse is a remarkably different way of knowing the body — of touching it, speaking about it, determining the source of its pains and discomforts — from that of biomedicine, where the pulse speaks through a blood pressure cuff, divulging its systolic and diastolic pressure. In a gorgeous book titled The Expressiveness of the Body, Shigehisa Kuriyama traces the history of these two different ways of knowing the body back to classical Chinese and Greek pulse-taking studies, exploring how physicians on opposite sides of the ancient world came to differently interpret the eloquence of the pulse, coming in turn to different conclusions about the body’s contents and functions, its disease and cure.

This way of feeling the pulse is a remarkably different way of knowing the body — of touching it, speaking about it, determining the source of its pains and discomforts — from that of Western medicine.

Kuriyama addresses an audience that understands the pulse simply as the regular expansion and contraction of the arteries as they circulate blood, and suggests, compellingly, that it — and the body — could be otherwise. Now, when I wrap my hand around the back of my wrist to feel my own pulse, steadfast and enigmatic, I’m not just looking to reassure myself of my own life. I also can begin to wonder about just how that life works, and how I can come to know it.

Illustration: Marjorie Wang