Mulan is known to Western audiences mostly as the hero of Disney’s 1998 animated feature, Mulan, which netted nominations for an Academy award, Golden Globe and Grammy, grossed $304 million, and treated audiences to deeply ironic sing-a-longs. It was a thoroughly bleached, Disney-ified rendition of the Chinese source material.

As it turns out, Chinese directors have been making and re-making Mulan since as early as 1939, when Xinhua Film Company (新华影业公司) released Bu Wancang’s Mulan Joins the Army (木兰从军, Mulan Congjun) in Shanghai. Similarities in the two versions are apparent. Bu’s Mulan, like Disney’s, outwits her entirely male and typically less-intelligent fellow soldiers, ultimately falling for the captain who follows her into marriage as she returns to domesticity at the close of the film. Both feature a tongue-in-cheek bathing scene with Mulan’s fellow soldiers, who in both versions are depicted as monstrously fat or tiny. Although Bu restrained himself to foot washing, while Disney indulged in full nudity, the correspondence is basically undeniable.

But according to Weihong Bao’s truly exhaustive analysis of Chinese film, Fiery Cinema, Bu’s film received special attention: in 1939, audience members were roused into a “riotous mass” during a screening of Mulan Joins the Army in Chongqing, setting fire to the theater’s stock of film reels in the street outside the establishment. The riot proceeded punctually from the first theater, the Weiyi Theater, to the second, the Cathay Theater, where the aroused audience promptly burned the remaining film reels stored there.

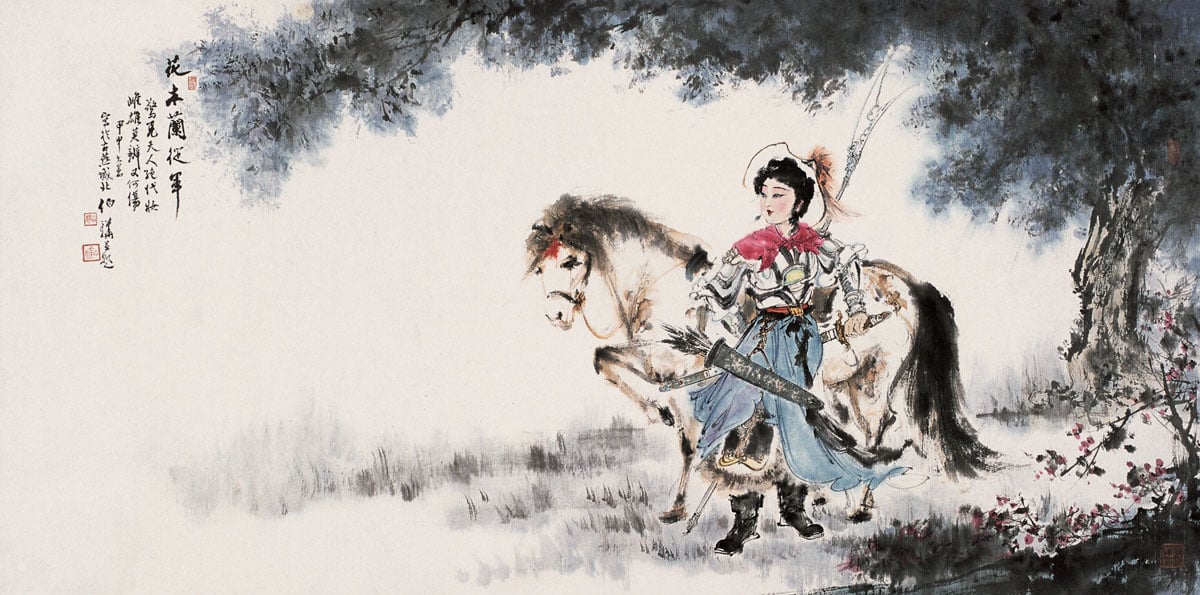

This wasn’t because Mulan Joins the Army was a bad film. It was actually met with critical success, adhering as it did to the generic conventions of the “costume drama,” with lavish costumes and sets and regiments of meticulously garmented soldiers and generals, much like Bu’s previous effort in the genre, Diao Chan, in 1938 (a portrayal of one of China’s “Four Beauties”). Mulan Joins the Army also featured Hong Kong starlet Chen Yushang in the titular role.

So what’s with the fires?

In 1939, Shanghai lay under Japanese occupation – and so too did its film industry. During the middle of the film’s screening, a man stood up on stage and accused Bu Wancang of collaborating with Japanese occupiers. This happened despite the fact that Mulan Joins the Army itself is a not-so-subtle nationalist film in which Hua Mulan takes charge of China’s defense against invading forces. (In Disney’s rendition, Mulan defends against the “Huns,” the epithet commonly applied to Germans during World War Two.)

The allegations against Bu weren’t unfounded: he directed two propaganda films for the Japanese government while they occupied Shanghai: Universal Love in 1942 and The Opium War in 1943. These blemishes in his filmography are emblematic of the complicated politics of Chinese film at that time, when the industry was heavily influenced by leftist directors and critics but operated under a nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) government characterized by a fundamental ambivalence toward socially conscious films. Indeed, Nationalist films were sometimes leftist – they featured poor characters who struggled against the rich and/or powerful, like Hua Mulan. KMT censors struggled to navigate between an imperative that films be socially progressive and a fear of leftist uprisings against nationalist rule.

The riot, according to Weihong Bao, illustrates much about this political moment. Film found its way to the center of a political and violent confrontation between Chinese nationalists and Japanese occupiers. What’s more, the riot was itself a type of orchestrated performance planned by opponents of the film: two dramatists and a filmmaker, who had tried and failed to convince Chongqing newspapers to publish petitions against the movie. Despite all that, Mulan Joins the Army was still better received than Disney’s Mulan II.

And wouldn’t you know it, Disney has a new Mulan in the works, a live-action movie – not a musical! – with a November 2018 slated release. Here’s to hoping it sees a calm, fire-free premiere.

| Column Archive |