Supervised by producer/director Ning Hao and led by actor Xu Zheng, Dying to Survive is currently raking in huge amounts of money at the Chinese box office. But at its heart is a real-life story that drove its protagonist to bankruptcy — and issues that continue to affect millions of people in China today.

Since the movie hit theatres on June 5th, it has garnered rave reviews and earned a score of 9.1 out of 10 among Douban’s notoriously hard to please online movie critics. In its first two days in cinemas, Dying to Survive also took in 150 million RMB (22.6 million USD), on route to accruing 1.3 billion RMB (200 million USD) by Monday morning. It now seems near-inevitable that the film’s total box office receipts will breach the 3 billion RMB (451 million USD) mark, and maybe, just maybe, Wolf Warrior 2‘s mega box office haul of over 5 billion RMB might be in sight. Quite a feat for a film that contains far more social commentary than Chinese blockbusters are generally known for providing.

Somewhat ironically, the film’s story is one of hardship and bankruptcy. In what can be seen as a Chinese Dallas Buyers Club-like tale, the real life protagonist Lu Yong endured illness, a total loss of savings, and legal prosecution, before ultimately becoming an online hero. And his experiences not only make for a dramatic screenplay, but also offer an insight into issues that continue to effect people across China.

CHINA’S DALLAS BUYERS CLUB

Sixteen years ago, Lu Yong, a comfortably well-off textile merchant from Wuxi in Jiangsu Province, was diagnosed with chronic myelogenous/myeloid leukaemia (CML). The doctor told him that he had about three years to live.

Lu was prescribed Gleevec, a cancer treatment drug produced by Swiss company Novartis, which at the time cost 23,500RMB for a box that would last a month. He took the drug for two years until he found he could no longer afford it. His savings had been almost entirely wiped out by the costly medicine.

In 2004 as he looked for alternative treatments, Lu discovered the existence of a generic Gleevec-like generic drug called Veenat, produced by an Indian company called Natco. A box of Veenat was priced at just 4,000RMB. The drugs were almost identical in terms of dosage and effectiveness, but the price was one twentieth of the original. (Years later, Lu would discover an even cheaper variant called Imacy, priced at just 750RMB.)

Related:

Here are China’s Big Summer Blockbusters for 2018Article Jun 30, 2018

Here are China’s Big Summer Blockbusters for 2018Article Jun 30, 2018

With the discovery of a drug at a much cheaper price, Yu’s hope of living reignited. He decided to illegally smuggle the pharmaceutical drugs from India in an attempt to prolong his own life. But he soon realized that there were thousands of patients with CML who, like him, couldn’t afford treatment, and so he began helping others to source the pills. He even helped the Indian suppliers manage Chinese bank accounts has his illicit drug trade took off.

Yet, as with Ron Woodroof in Dallas Buyers Club, who faced opposition from the US’s Food and Drug Administration, Lu also encountered harassment and ultimately legal charges for selling “fake” cancer drugs. On July 21, 2014, the Yuanjiang City authorities charged Lu with “impeding credit card management” and “selling counterfeit drugs”.

Yet more than a thousand patients whom he had helped petitioned the court and on January 27, 2015, the lawsuit was withdrawn. In a note regarding the dropping of charges, the prosecutor wrote:

“If Lu’s behavior is considered as a crime, it will deviate from the values of criminal justice.”

Lu Yong was eventually released without charge.

Lu’s story became national news and was widely discussed on Chinese social media at the time, with many declaring him a hero. But his story — an now this movie — have drawn people’s attention to the broader issue of how expensive cancer treatment is in China and why pharmaceutical giants continue to charge such high prices for drugs.

POVERTY DUE TO ILLNESS

Both In the movie and in reality, patients resort to acquiring “illegal” generic drugs for one reason: genuine patented medicines are too expensive.

In China, treatments for any major disease, but especially cancer, is largely unaffordable for working-class families. Cutting edge anti-cancer drugs, such as PD-1 inhibitors for example, cost at least 100,000USD here.

“Poverty due to illness” has become one of the biggest single causes of poverty in China as malignant tumors become prevalent. Patients are often told by doctors: I know of an effective drug, but telling you is useless: you can’t afford it. There are affordable treatments, but you can’t buy them in China.

Over the course of just two years, Lu Yong spent a total of 564,000RMB (85,172USD) on Gleevec following his diagnosis with leukaemia.

As treatments in China improve, so medical expenses increase — but often far faster than people’s incomes. This leads to people across the country facing a horrific dilemma: either die from disease or die from poverty.

Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry in China, as with many other parts of the world, continues to be a profitable business. Swiss firm Novartis’ annual sales of Gleevec total nearly 5 billion USD, with the market price in the States having doubled in seven years.

Those in the industry point to the expensive costs of research and development as justification for these high prices. While generic pills can cost a fraction of the original, the work that goes into developing pioneering new medicines in the first place is not cheap. According to a 2014 report from the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, the average cost of developing a new prescription drug is 26 million USD, and after it’s been examined and approved by the FDA, there will be a further 3.12 billion USD necessary to research the strength of dosage, different recipes, and potential side effects.

Novartis started its research on CML drugs in 1988, spending huge sums of money on the a pill that can increase a patient’s five-year survival rate from 50% to 90%. Only after more than a decade, did it pass the examination and get approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2001.

After the invention of a drug, pharmaceutical companies usually apply for patents that last for 20 years to make sure their IP is protected and they can recoup their investment.

You might also like:

How China is Leading Genetic TechArticle Aug 22, 2017

How China is Leading Genetic TechArticle Aug 22, 2017

This is a situation that plays out in markets across the world. However, the price of many drugs in mainland China is often higher than in any other country; not only is Gleevec’s price in China double that in the US and South Korea, but also the prices of 80% of imported original drugs in China are higher than those in Hong Kong.

Many people in China are perplexed by this situation, and believe that as the country with the biggest population of patients, China should have more bargaining power.

SO WHY ARE DRUGS SO MUCH MORE EXPENSIVE IN CHINA?

“Unlike Hong Kong, China has 5% tariffs and 17% value-added tax. And the hospitals usually sell the drug to the patients at a price 15% higher than what they bought with,” said Guo Jianying, deputy inspector of the Price Department of the National Development and Reform Commission, according to a recent report by Tide Workshop. In the US, the UK, and Australia, the VAT for medicines is zero and most European countries have policies that ensure lower rates of VAT for drugs.

Another factor is that in China, multinational pharmaceutical companies have the privilege of setting the price for imported original drugs even after their 20-year patents expire, although for domestic drugs the Chinese government sets a “guiding price”.

Additionally, imported drugs have to go through clinical trials before entering China even if they have been approved and used in overseas markets for many years. These trials require a large amount of clinical data and can take three to five years to complete.

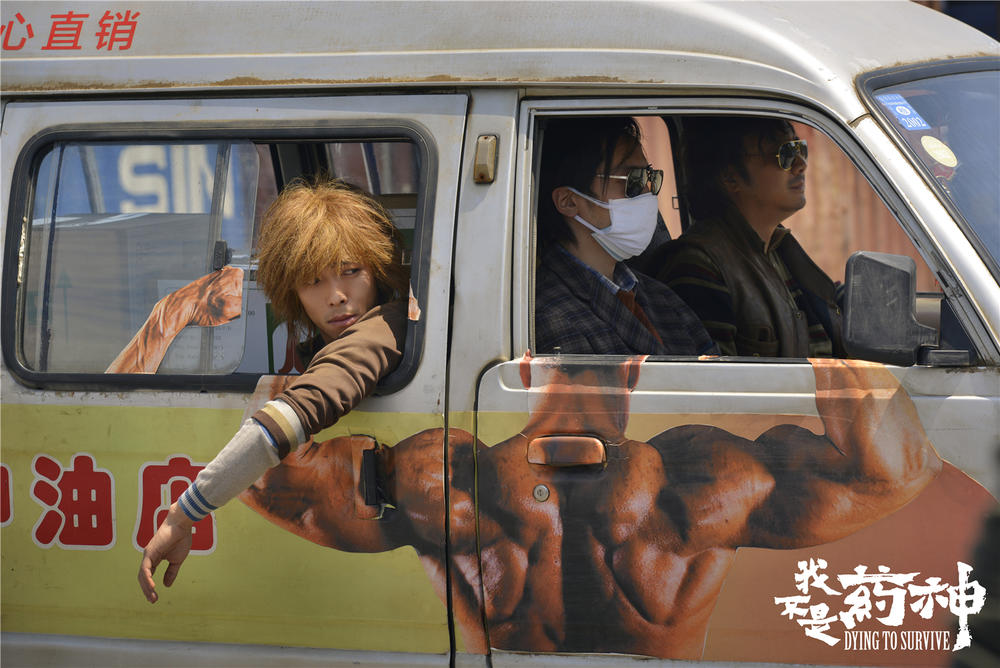

A poster for Dying to Survive

According to data disclosed by Beijing Continental Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. in 2012, the cost of conducting Phase III clinical trials in China is approximately 3-7 million USD. However, in most countries, clinical trials are not needed for imported drugs. To save costs and shorten development time, many countries use drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration directly, but China does not recognize the organization’s data.

Therefore, it’s not surprising that the world’s 15 largest multinational pharmaceutical groups continue to invest huge research expenditures in China. In the past decade, these have seen an annual growth rate of 22.5%. Much of the cost of this scientific research and administration therefore continues to be paid by Chinese patients.

China’s medical environment is improving however. On May 1st, 2018, the Chinese government implemented zero tariffs on 28 kinds of imported drugs. Additionally, the VAT for the import of anti-cancer drugs (including 103 anti-cancer drug preparations and 51 kinds of anti-cancer drug raw materials) was reduced by 3%.

At the same time, the State Food and Drug Administration has accelerated the process of approval for new drugs. Taking cervical cancer vaccine (HPV) as an example, the bivalent and tetravalent vaccines had to undergo 10 years of experiments before being licensed and listed in China. However, it took a mere 8 days for the nine-valent vaccine to be approved.

Moreover, China also joined the International Conference on Harmonization of Human Drug Registration (ICH) last year, which means China will aim to share data and coordinate technical standards with other countries such as the US and Japan in the hopes of reducing the cost of drug development.

The idea that life-saving medicines are a luxury that only the wealthy can afford is understandably a sensitive one in China — as in the US and other countries. Improvements are being made, but there are still important issues at the crux of the pharmaceutical industry that need to be addressed. Dying to Survive may have all the slick drama and whacky moments of classic summer blockbuster fodder, but it does dig a little deeper than most, and it deserves credit for putting these issues back in the public spotlight.

—

Cover photo: Xu Zheng in Dying to Survive

You might also like:

What Do China’s Moviegoers Look For at the Box Office?Article Sep 15, 2017

What Do China’s Moviegoers Look For at the Box Office?Article Sep 15, 2017

China Announces Major Research Centers in Beijing and ShenzhenArticle Apr 11, 2018

China Announces Major Research Centers in Beijing and ShenzhenArticle Apr 11, 2018

China Clones Monkeys, “Races Ahead” in Gene EditingArticle Jan 25, 2018

China Clones Monkeys, “Races Ahead” in Gene EditingArticle Jan 25, 2018