In China, the process of assimilation for a given Western cultural artifact tends to be largely the same. Whether it’s a TV show or a fashion trend, the arc of its travel goes from a state of popularity abroad, to a base of early adopters in China, to a portion of those early adopters creating a China-contextualized version, to mainstream success and popularity. The journey can be slow or fast, but the internet has obviously sped things up considerably. So I guess it only makes sense that vaporwave is pretty much here now.

Vaporwave, of course, being the joking-yet-serious internet-born microgenre of music/art that belongs to no place or time. If you haven’t heard of it, don’t kick yourself. The music is largely defined by its own fleeting nature, building homes in esoteric corners of Soundcloud and Bandcamp, shrouded in Japanese characters and A E S T H E T I C S. It’s been described as the first style of music free of a geographic origin, having been birthed directly out of the anonymous, flickering womb of the internet.

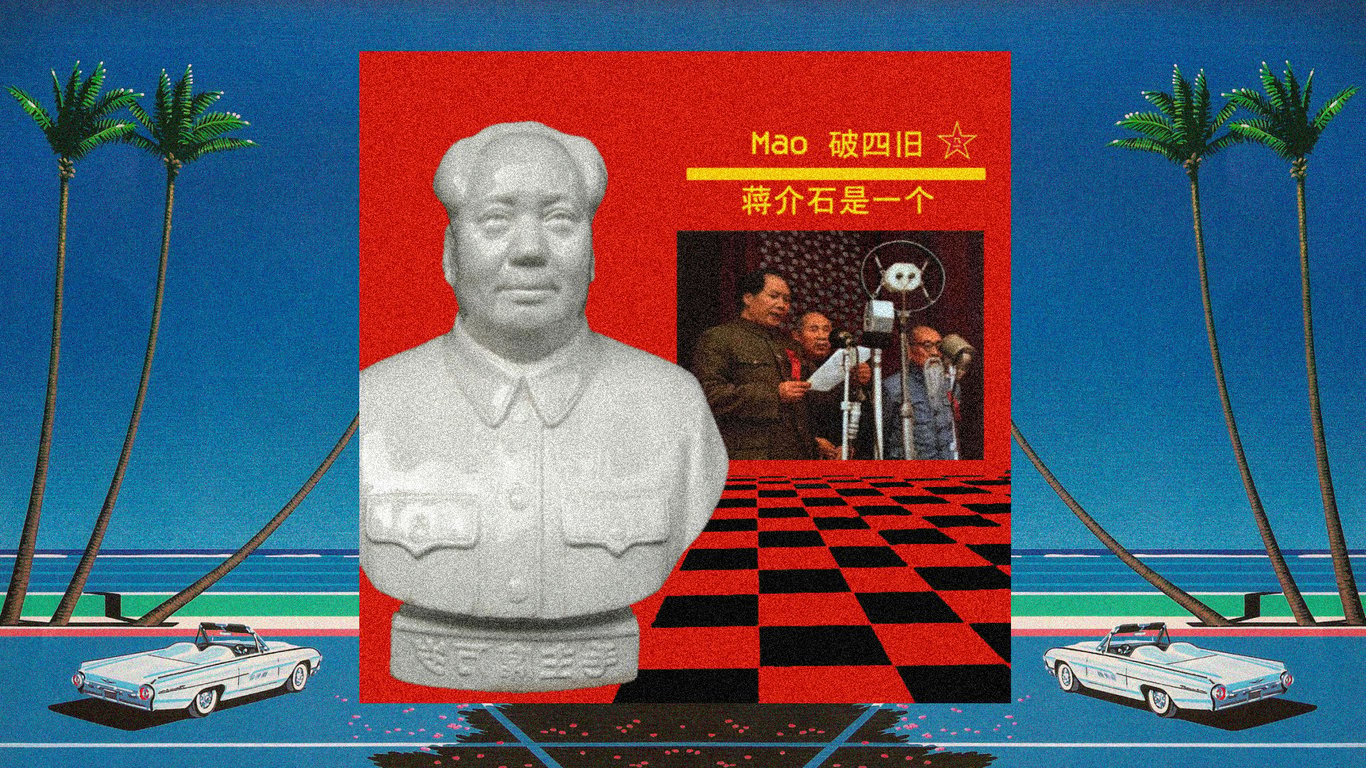

What are we looking at here

It’s driven by a grab bag of diverse influences. Recurring themes include, but aren’t limited to: cynicism toward consumer culture, 1990s nostalgia and computer technology, cyber-dystopian unease, and East Asian iconography. It’s the product of a generation of ’90s kids who arrived at adulthood just in time to see the world burning down around them. Traditionally, the music relies on layered samples of ’90s pop, R&B, and elevator music slowed down past recognition to achieve its eerie, anachronistic vibe. It’s calming, but also somehow distinctly unnerving. The visual aesthetic is equally important — old-school 3D, classical statues, and the Windows 95 user interface have all found themselves absorbed into vaporwave culture.

We’ve talked a lot recently about how hip hop has finally eked its way into China’s mainstream. Honestly, that took forever. But could you really expect anything different? We’re talking about a genre that was created in the ’70s by black and Puerto Rican youth in the Bronx. When hip hop was invented, not only was the idea of electronically editing music a completely new concept, but China was in the throes of the Cultural Revolution, where non-Maoist music wasn’t even allowed to exist. So by the time that ended, China had to build its own concept of pop culture from the ground up, in an era when phones had wires, all while simultaneously trying to re-orient itself as a functioning modern state — China can be forgiven for not rushing to “get” hip hop music.

China had to build its own concept of pop culture from the ground up, in an era when phones had wires, all while simultaneously trying to re-orient itself as a functioning modern state

Hip hop, China, and vaporwave collide in a Nivea skincare ad featuring Rap of China finalist Brant.B

But with vaporwave, the process was almost immediate. Culture is becoming uniform across the world, with the ideological gap between places shrinking, and this is especially true of youth culture, since young people are the most plugged in to the internet.

Vaporwave having come from the collective internet itself, it’s not much of a jump for Chinese audiences to understand it, despite not having grown up around certain themes of nostalgia that it’s based in. And if a bunch of American millennials can decide to actively incorporate Japanese Coca-Cola ads from the ’80s into an art movement, then China can damn well appreciate heavy imagery of Arizona iced tea (these themes sound weirder and weirder the more I write).

If the global unification of culture is the result of our increased capacity for communication via the internet, one might feel tempted to jump out and say Hey Adan, that’s all well and good, but what about INTERNET CENSORSHIP IN CHINA, and I would say woah, man, cool it with the all caps.

Yes China’s internet is censored, but it doesn’t really halt the spread of trends like this, and that’s mostly because wherever there is a gap in coverage, local platforms step in to fill it.

So while listeners might not be able to search up the tracks they want on Spotify, they definitely can on QQ Music. They can’t follow a vaporwave tumblr for all their aesthetic needs, but they can follow a WeChat page. The Chinese internet exists as a mirror to the greater internet, that for the most part kind of has all the same stuff. As an American, I instinctively recoil at the thought of the government choosing what goes on the internet. But for most Chinese people I’ve talked to, it’s not a huge deal — they’d likely rather use the Chinese version anyway.

No shortage of vaporwave content on WeChat

The last thing I’ll mention is that in an increasingly capitalist China, someone’s always looking to make some renminbi. Major brands are always looking to capitalize on something hip, leading to greater exposure for the thing, which makes more brands want to use it. It’s a vicious cycle.

Banner from the front page of Taobao

The one true rule of Taobao: if it exists, it exists as a phone case

Not really sure what the takeaway is here, but it is mind boggling to see how fast something that is supposedly niche and esoteric is processed, packaged, and shipped overseas to a swarm of eager young minds in China all looking for the next big thing, in an age where “bigness” lasts about fifteen minutes. I asked my friend Raven, a vaporwave fan from Nanjing, about her thoughts on all this:

I first heard about vaporwave as a recommendation from the music app Wangyiyun. I found out the music videos for it always had the same style so I Googled it and started liking it a lot. I like psychedelic music, and vaporwave had the same vibe, with a strong sense of future. Vaporwave is kind of a niche subculture right now in China, but once you get the spirit of it you can find it easily in daily life.

I asked her how she felt about the commodification of an anti-consumerist art movement, and how Chinese millennials would feel about products like the above being marketed via vaporwave.

“I believe young people will definitely love it.”

Semi-related:

Twitter Bits: Deep TaobaoArticle Oct 18, 2017

Twitter Bits: Deep TaobaoArticle Oct 18, 2017