The filmmaking and video content creation world are constantly evolving with the advent of new technology. Today, high-quality images are accessible to anyone who dares to learn the craft — you no longer need a massive budget or industry connections to bring your vision to life.

Leonardo Dalessandri’s journey into the cinematic world began with neither. The Italian filmmaker received his first camera — a large Panasonic — from his father at age 11, which he would use to document the family adventures of his youth.

In the years since, he has turned his camera towards the wider world, using his lens and unique vision to capture the lives of strangers beyond his Mediterranean homeland.

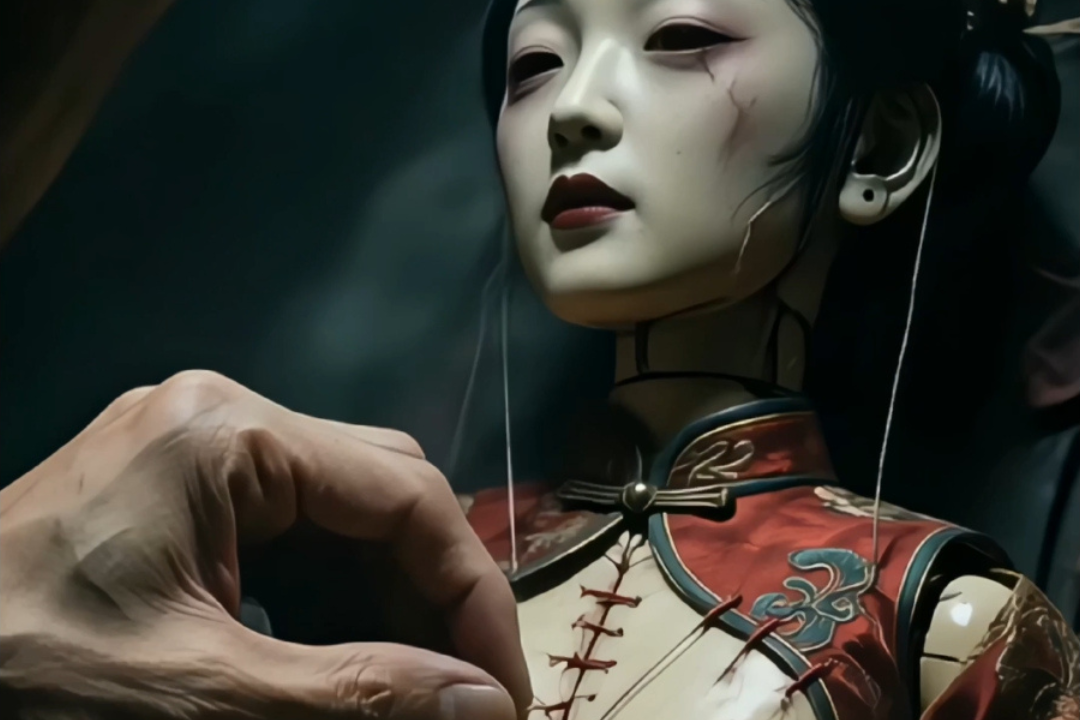

With the 2014 release of Watchtower of Turkey, the relatively unknown Dalessandri sent a shockwave through both the YouTube content creator community and professional film and commercial industries with his visually stunning and profoundly emotional short film spanning the transcontinental Eurasian nation.

After nearly eight years, Dalessandri has blessed the world with another sonic boom — introducing viewers to the sights and sounds of the most populous nation on Earth like you’ve never seen them before.

Watchtower of China has all the signature stylings of his previous works, while pushing beyond the ambition of his earlier masterpieces. Volume up. It’s worth it.

Dalessandri’s style is hard to describe. The ever-flowing motion of his camera work combined with his seamless edits, and the way he captures raw humanity — the faces, essence, and souls of his subjects — is astounding, to put it simply.

“This film is not a statement to China. I’d like it to be a personal vision of a foreigner about their country,” said Dalessandri in an article for Final Cut Pro, his preferred editing software.

“You can find literally everything you want in China, from the most extreme to the most basic, poetic, and cultural things. But when you get to know this country a little bit, you start to feel its real spirit.

“It took me a few months to get in this mindset, to find the right pace and quiet. It’s a big place full of people that are connected through energy. And you feel this in how they live, in how seriously they take their work, in their dignity, in their honesty, in how they do yoga, tai chi, ballet, in how they make music, in how they prepare food.”

Dalessandri’s visual journey took more than five years to complete. He shot the footage in three-month periods over three years, with a crew of 20 people traveling in a minibus to 72 cities and sites across China. He then spent two years editing from his place of residence in Istanbul throughout the Covid-19 pandemic.

Chinese producer Polo Zhao was a pivotal contributor to the film’s success. When Zhao heard that China was the destination for the next Watchtower project, he reached out to help with production.

“The director of Watchtower of Turkey is looking for assistants to make Watchtower of China,” Zhao posted to his personal blog before shooting began.

Many students and film lovers soon responded, offering to help for free, for both the learning experience and as a gift to their home country.

Throughout the years of shooting, Dalessandri had two assistant directors: Jolien from Amsterdam and Ricky from Hong Kong, as well as three to four people behind the cameras at any given time, one recording ambient sound, and many others helping with administration, organization, and other roles.

Reflecting on the undertaking, Dalessandri emphasized his appreciation for the passion and commitment of his team.

“During one of our trips, we spent a few nights in the mountains. We had been hiking all day and were very tired. When I woke up early in the morning, the crew was already hard at work. Someone surprised me with a time-lapse he had shot a few hours before, and another one showed me some interesting spots he had found where we could take beautiful pictures,” he said, adding, “I feel a deep love and respect for everyone I have worked with on this project.”

Dalessandri and his crew used a wide variety of lightweight equipment. DSLR and mirrorless were the obvious choices for cameras, namely the Sony A7 ll, A7 lll, and RX-100, as well as a China-made Z-cam on his last visit to Hong Kong.

The crew also used Edelkrone sliders, DJI drones, and 40 different lenses, including Chinese-made Dulens prime lenses, to capture a variety of unique motions and perspectives.

The four-minute final edit contains 297 video clips and many hundreds of audio clips selected from a 300-terabyte library of footage. In the end, there were over 24,000 clips to choose from.

Furthermore, there are no transitions in the film — the final edit utilizes cuts only. Many are composite clips with multiple layers, masks, color corrections, and de-noise filters.

“It’s mainly about developing a directing style that is 100% connected to the edit […] My style is based around creating cinematic cuts that are driven by matching camera movements or matching content between shots,” said Dalessandri.

“Creating this feeling of permanent continuity in the edit has actually a lot to do with the way the shots are recorded […] How should I move the camera during the shoot to achieve the edit I want? It’s very important to think about this during the shoot. If you have to ‘fix’ things in post, you often lose the power and the natural flow of your edit.”

The combination of camera movements, fluid, invisible cuts, and sound design were all motivated by the pace of Dalessandri’s chosen music — compositions by multifaceted Italian composer Ezio Bosso (1971-2020).

Dalessandri combined two Bosso compositions — ‘Rain, In Your Black Eyes’ and ‘Thunders and Lightnings’ — into a single soundtrack. Bosso’s repetitive yet ever-changing verses are layered atop one another, creating an earthquake of emotional crescendos.

The four-minute track played on repeat while Dalessandri walked around Turkey and Italy, imagining all the while how the China film would play out.

“I heard the music of my film on TV with the news that Ezio Bosso had passed away. I was in tears. I had spent the past five years with that music in my head, and I had hoped to send Watchtower of China to him as a tribute to his work,” said Dalessandri.

“I cannot tell you how many times I have walked through my room in the dark, listening to the music and trying to imagine what images would work best with the feelings I want to convey.”

Visitors to China will see a country of great contrast: fast-paced and hectic, slow and rhythmic, ancient, traditional, modern, dynamic, and constantly evolving.

Dalessandri’s visual journey across China portrays these concurrent and contradictory realities “by constantly changing the rhythm in the movie, mixing fast-paced images and city sounds with moments of calm, of reflection, of human interaction.”

Above all else, the people of China are at the forefront of this monumental undertaking. His subjects’ smiles, rituals, and daily lives encapsulate the essence of a nation that is difficult to put into words.

“That’s the message of this film. This is not commercial. It’s a constant flow of impressions and images that convey everything I felt when traveling through this beautiful country,” said the filmmaker.

“If my new Watchtower can make you so intrigued by what you see […] that you want to learn more about China and its people, I will consider this a success.”

Cover image: screengrab via YouTube