Art and China After 1989: The Theater of The World opened on October 6 at the Guggenheim in New York with a heavily modified version of its eponymous work, and absent two other installations originally included in its program. All three facets of the blockbuster exhibition were targeted by a swift and brutal internet campaign by animal rights activists. Curators at the Guggenheim eventually claimed threats received by the museum jeopardized public safety — they contacted the police, and the art in question disappeared from the exhibition.

Chinese Art Provokes Innovation, Protests and Censorship AbroadArticle Sep 28, 2017

Chinese Art Provokes Innovation, Protests and Censorship AbroadArticle Sep 28, 2017

The irony is delicious. The New York Times wrote in a preview on September 25 that “The uninhibited avant-garde art at the Guggenheim will offer a jagged contrast to Mr. Xi’s stiff internet censorship.” September 25, according to a report in the same pages two weeks later, happened to be the same day on which “the museum decided to pull the three works.” At perhaps the exact moment the Times was scribbling the praises of “uninhibited” avant-garde art, curators were huddled somewhere in the Guggenheim’s back offices pulling the plug.

Art and China After 1989 made headlines for the removal or modification of those three works, but it is still vast in scale, featuring 147 pieces by 71 artists. The exhibition is also accompanied by a documentary film series, Turn It On: China on Film 2000-2017. I recently had the chance to catch two days of poorly attended screenings in the series at the Guggenheim’s New Media Theater.

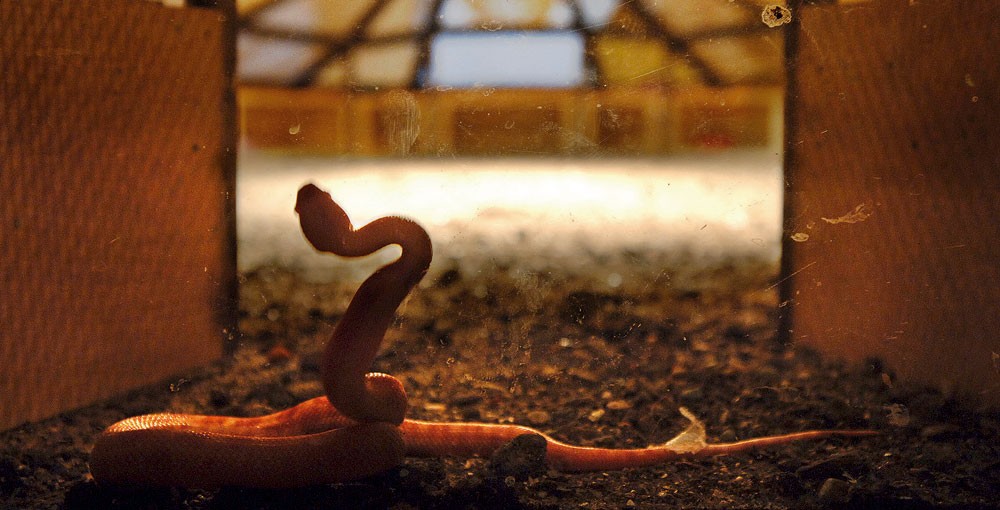

Art and China after 1989 installation view

According to the museum’s press release:

The works in this series offer urgent and often raw insight into issues of personal struggle and social justice…[the films] are made by writers and artists with little to no cinematography training.

This is true. The films were selected by internationally renowned artist Ai Weiwei and Wang Fen, who told CFI, “Admittedly, some of the films we are showing this time are really long, much longer than the films we usually see in movie theaters.”

On a recent Saturday afternoon I saw Apuda, a film about an impoverished Nakhi father and son living in Yunnan. The widowed father is bedridden, and requires constant care from his son, who cannot work the fields. The film is two and a half hours long, and I do not believe it contains a single shot shorter than three minutes. The camera never tracks, and patches of dialogue are few and far between. There was much less movement on-screen than in the theater. People wandered in for a few minutes — one shot, on average — became bored, and wandered out again. It could and probably should have been a photography series.

Related:

Looking Back to the Future of Chinese FilmArticle Oct 03, 2017

Looking Back to the Future of Chinese FilmArticle Oct 03, 2017

Nightingale, Not The Only Voice, screened the previous day, is a three-hour film shot by artist Tang Danhong that follows the lives of three artists: two severely depressed, including Tang, and one severely alcoholic. The work is reminiscent of Suzhou River in terms of composition and tone: both portray alienated, lost souls with the shaky ambience of hand-held cameras.

In what passes for a climax, all three artists unite with their friends in a Western-style bar for New Year’s 1999, where the alcoholic gets belligerent and the depressives get sad. “The pub is a spaceship,” says Tang in voiceover. The film eventually closes as she interviews her parents about the emotional and physical abuse she suffered at the hands of her father, which her mother blames on the lingering violence of the Cultural Revolution, while he stares silently through the shot. Curtain.

It is an extremely disaffecting work that begins to haunt after an hour, when you realize you would very much like it to end. It continues to screech onwards for another 120 minutes. The film strikes me as embodying everything everyone hates or loves about Kerouac, but for the 1990s artistic class in Beijing.

The shorter films had more to them, and one of them in particular stood out. Readymade (现成品) is a short biopic by artist Zhang Bingjian, known for his portraits of corrupt officials, and features two of the approximately twenty Mao impersonators active in Mainland China: Chen Yan, a woman, and Peng Tian, a man.

Chen Yan

Peng Tian enrolls himself at the Beijing Film Academy in order to study acting and improve his Mao. He listens to recordings of the Chairman’s speeches and meticulously rehearses his stringy, high-pitched smoker’s whine. His tuition is financed by his wife, whom he left in Hunan, where she runs a small grocery stand in Zhangjiajie National Park. Unlike Chen Yan’s husband, Peng’s wife agreed to be interviewed. She speaks admiringly of his dedication, but breaks into tears when pressed about the financial and emotional strain his studies in Beijing have put on the family. For a moment she turns away from the camera and wipes her eyes behind a rack of instant noodles.

Chen Yan sheds some tears, too, when asked about her husband’s intense hatred of her hobby. The film glosses over it, but near the end it becomes clear that for Chen Yan (and certainly for her husband) her obsessive pursuit of the perfect Mao — the mole she places on her chin, her total silence in character, and a pair of specialized platform shoes that add 27 centimeters to her frame — calls into question a kind of gender politics. Chen’s devotion is inescapably comparable to drag, and perhaps the complex politics of gender can explain why Chen is sanctioned by the police, who end one of her street procession performances early and without explanation, but Peng Tian is not.

It is Chen’s makeup artist who most clearly articulates her intense devotion to the craft and her anguish at her family’s lack of support. The platform shoes Chen wears cost 17-18,000 RMB (about $2,700), though luckily she received support from her cobbler early on, and the shoes were donated to her cause. The makeup artist in the film isn’t sure if Chen is even reimbursed for her ten or twenty performances a year, although according to the South China Morning Post, Chen’s circumstances have since improved: they estimate she earns 2,000 RMB (~ $300) per performance, and report that she and her husband have reconciled.

What exactly Chen Yan and Peng Tian’s motivations might be is a more complicated affair, and it probably depends who you ask. There is a stark difference between the way Peng and Chen’s work is treated in the film, and the way they view it themselves.

On the one hand, it’s obvious that their audience treats them as street performers. In the film they precede Michael Jackson impersonators or teenage dance crews on improvised stages in bars and light-hearted street festivals. They elicit smiles, laughter, and smartphone cameras, but not devotion or anything resembling the adoring treatment granted actors or “real artists.” In the eyes of their audience, Peng Tian and Chen Yan do not have what Walter Benjamin called “aura.”

Still from Readymade (现成品)

In Chen Yan and Peng Tian’s eyes, on the other hand, Mao is all aura. It is abundantly clear they see their work as a holy labor of devotion and worship — some might call it idolatry. Chen Yan has a shrine to Mao in her home, where she has hung portraits of herself in costume beneath actual pictures of Mao, and where she prays to him every morning. They cannot quite explain why they do what they do, but both share stories about the first time their likeness to the Chairman was noticed by a friend, and as if by divine providence, their paths were laid clear before them.

The film’s title does contain a hint as to what the larger artistic and political implications of Chen Yan and Peng Tian’s art, if we can call it that, could be. “Readymade” as a concept has an international legacy in contemporary art. The term originated in the United States in the early 20th century, referring to quotidian, mass-produced and commercially available products like bicycles, shovels, and hammers. Marcel Duchamp famously appropriated the term, and introduced a revolution in the world of contemporary art when he began submitting these products to art juries for exhibition. The revolution was consummated when such juries began accepting these “readymades” — most notably, Duchamp’s Fountain, a repurposed urinal.

Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei has riffed on this concept in works like Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (above) and Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Logo, where the veneration of “ancient” and “traditional” Chinese culture is manipulated and perhaps critiqued by juxtaposition with quotidian materials like the Coca-Cola logo, or destruction by an artist who sees veneration and idolatry in a dusty old vase.

Both of these works appear in the Guggenheim exhibit, and we should remember that Ai Weiwei co-curated the series in which this film about the manipulation of Mao’s image — an idol if there ever was one — is featured. The everyday veneration of urns and of Mao is juxtaposed with Ai’s casual destruction, on the one hand, and Chen and Peng’s near-religious worship, on the other. These artists’ work might flatter themselves, but for the masses, it is cheap entertainment.

Zhang Bingjian’s Hall of Fame series (source)

David Moser, writing about Mao impersonators in 2004, said that “There is, in fact, no political satire at all in China.” Yes and no. Certainly Chen Yan and Peng Tian would not consider themselves engaged in Western-style political satire. Moser is looking narrowly for a particular Western form when as asks where the “Chinese Lenny Bruces, Dick Gregorys, or Richard Pryors are.” That misses the point. Chinese political satire must necessarily take a different form, and it might be useful to ask in parallel: Where are the American Zhang Bingjianses?

And how does Zhang ask us to look at Chen Yan and Peng Tian, ultimately? Considering his work on those many hundreds of portraits of corrupt politicians in the pinkish hue of 100 RMB notes (above), one might conclude, contrary to Pete Brook of Wired, that irony is the dominant motif. Readymade begins with shots of the Forbidden City, decorated with Mao’s gigantic portrait and facing his mausoleum. In this framing, Mao-as-symbol has surpassed Mao-the-human.

But the sincerity with which Peng Tian and Chen Yan assume Mao Zedong characteristics while believing that their performances are apolitical poses a mesmerizing question begging the kind of artistic exploration Zhang Bingjian delivers. With Readymades, Zhang has taken note of his culture’s tragicomic potential. If only the New York Times would do the same of theirs.

The Turn it On Film Series continues at the Guggenheim through January 4; find the program here.

Cover image: Zhang Bingjian (Rancho Las Voces)