China’s Digital Renaissance is a series exploring new currents in Chinese contemporary art, created in partnership with East West Bank. This article centers on Xu Bing, who paradoxically uses text to create powerful visual art.

Xu Bing is one of the biggest names in Chinese contemporary art, whose innovative work explores the way that language, words, and text shape our perception of reality,

“I have a distance from others, but when I give this work to society, this sense of distance is gone.”

Xu Bing has been active in the art community for over four decades, even serving as Vice President of China’s Central Academy of Fine Arts, and as an A.D. White Professor-at-Large at Cornell University. As if those accolades weren’t enough, he’s also won awards including the Fukuoka Prize and the MacArthur Fellowship “Genius Grant.”

Born in Chongqing in 1955, Xu Bing moved with his family to Beijing soon after, where his father was the head of Peking University’s history department. Xu’s own scholarly journey began when he enrolled at the Central Academy of Fine Arts to study printmaking.

That experience in printmaking set the foundation for Xu Bing’s unique artistic style, using language and text in novel and unorthodox ways.

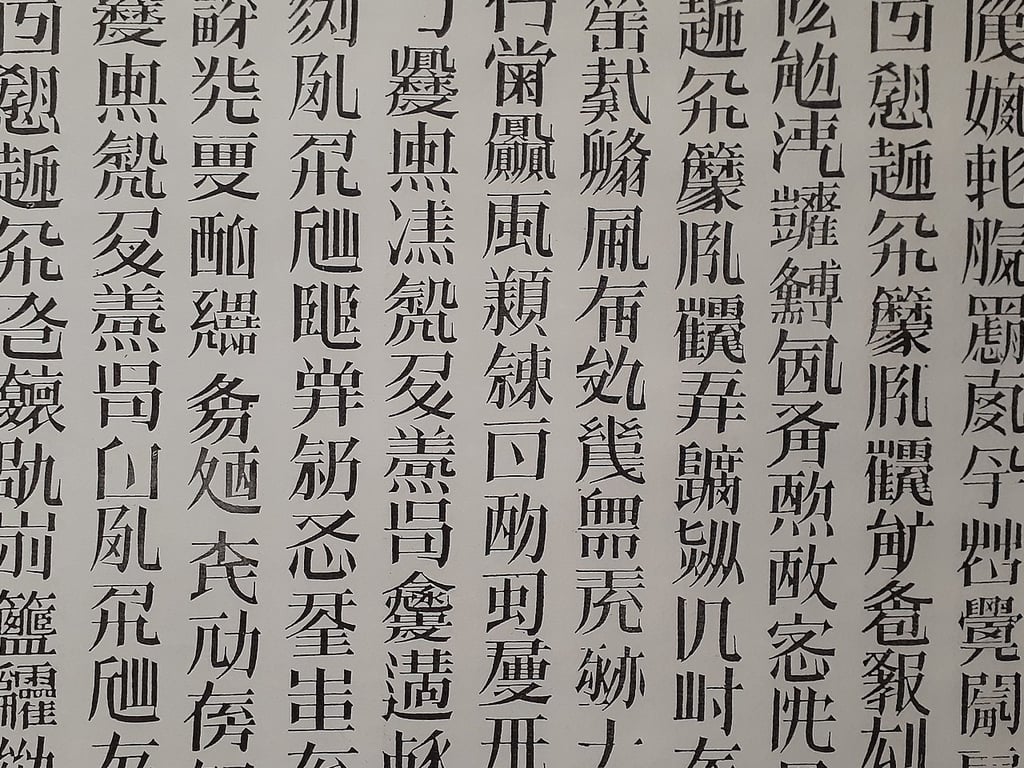

In “A Book from the Sky”, for instance, Xu Bing invented 4,000 brand-new “Chinese characters.” The characters weren’t real — they were essentially unreadable gibberish. Xu made them into movable type, printing books and scrolls which covered floors and ceilings.

“The audience looks and wonders why some words seem unfamiliar. Then they look again and find more words they don’t know,” Xu explained. “Finally, when they realize they don’t know any of the words, they begin to doubt, because the whole world is a bit upside down.”

“Actually, I used the special rules of Chinese character formation. I wanted it to look as much like Chinese characters as possible, without being Chinese characters,” he added.

It took Xu almost four years to complete the project, but he doesn’t regret a minute of it.

“I really had a sense of nobility at that time. I felt that locking myself in the room and carving these Chinese characters was more noble than queuing up to buy vegetables in life,” he recalls.

Xu’s more recent works haven’t lost that experimental feeling. Last year’s Gravitational Arena played with the theme of gravity — the installation piece presenting a “vortex” of 1600 characters, elongated as though being sucked through a wormhole. The piece extends down to the ground from a height of over 30 meters, where it meets a large mirror on the floor, creating a sense of movement and depth.

“The shape of the work and the mirror reflection are similar to the ‘wormhole model’, and the ‘arena’ reveals the dramatic experience when viewed from different angles on different floors,” Xu said. “By simulating the entanglement between matter in the universe, I hope this work can evoke the audience’s thinking about the tension, interaction and wrestling relationship between different civilizations.”

Today, Xu’s work continues to evolve, as he explores the use of tools like AI.

“I’ve never loved art more, and in the future, as AI develops, humanity will need art even more,” he told RADII.

Cover image via Meikowkmeomi Othumddroa