Artist Zheng Chongbin was born in Shanghai in 1961, and has been based in the San Francisco Bay Area since 1988. This condensed biography might at first glance suggest a straightforward equation for understanding his diverse practice: Chinese roots plus American modernity. Yet even as this succinct breakdown offers an opening into his work, it fails to capture the complexity of the paintings, installations, videos, and more he has crafted over the past four decades. Merging techniques from traditional Chinese ink painting and Western abstraction with conceptual thinking inspired by Daoism, the California Light and Space movement, and New Materialism, Zheng’s art blurs distinctions between styles and orthodoxies, inviting viewers to embrace the innate qualities of his materials and their interactions with light.

Zheng came of age in the 1980s, as China’s art world went through a period of radical change, leading to the birth of Chinese contemporary art. However, his early artistic education was grounded in tradition: he studied ink painting with masters Mu Yilin and Chen Jialing before heading to the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (today the China Academy of Art) in Hangzhou. In these years, he learned to use maobi (soft-bristled narrow brushes) to subtly control the flow of ink of across xuan paper, the medium of choice for Chinese painting and calligraphy for more than a millennium.

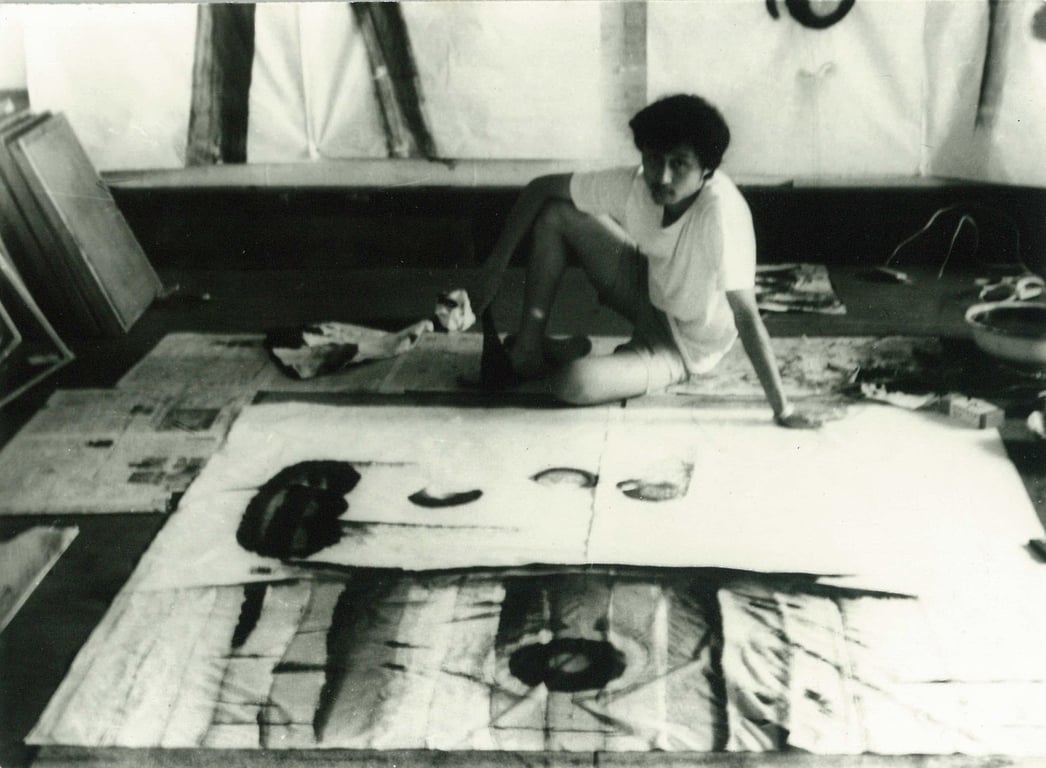

Graduating in 1984, Zheng would teach at his alma mater for the next four years. It was a time of creative ferment. As new cultural influences flooded into China, artists, critics, and curators coalesced into the ’85 New Wave movement, with the art academy in Hangzhou serving as a key node for intellectual debates. Zheng himself moved towards abstraction, experimented with wider and stiffer paibi brushes to break out of established patterns of painting, and mixed white acrylic and ink to create what he called “white ink.”

Another State of Man No. 24 (1988), held in the collection of Hong Kong’s M+, provides a snapshot of his style at the time: though still based on vague, surreal figuration rather than pure abstraction, the nearly three-meter-tall painting’s dimensions and wide elemental brushstrokes seem to foreshadow the massive installations he would make in the years to come. Indeed, not long after staging his first solo exhibition at the Shanghai Art Museum in 1988, Zheng received a fellowship to study for his Master’s at the San Francisco Art Institute, where he would dive into installation, performance, and conceptual art.

Working from his new home base, Zheng’s art was shaped not only by the contemporary mediums he encountered in his Master’s studies, but also the Bay Area’s natural environment — its unique interplay between land and sea, light and atmosphere. Today, these influences are fully incorporated with insights gleaned from Daoism and pre-modern Chinese thought, namely the idea that world is in a constant state of flux. Zheng’s conceptual thinking has fuelled the creation of artworks in which ink and other materials become art in their own right, imbued with a sense of agency and mutability, taking on different aspects depending on lighting and the perspective of the viewer.

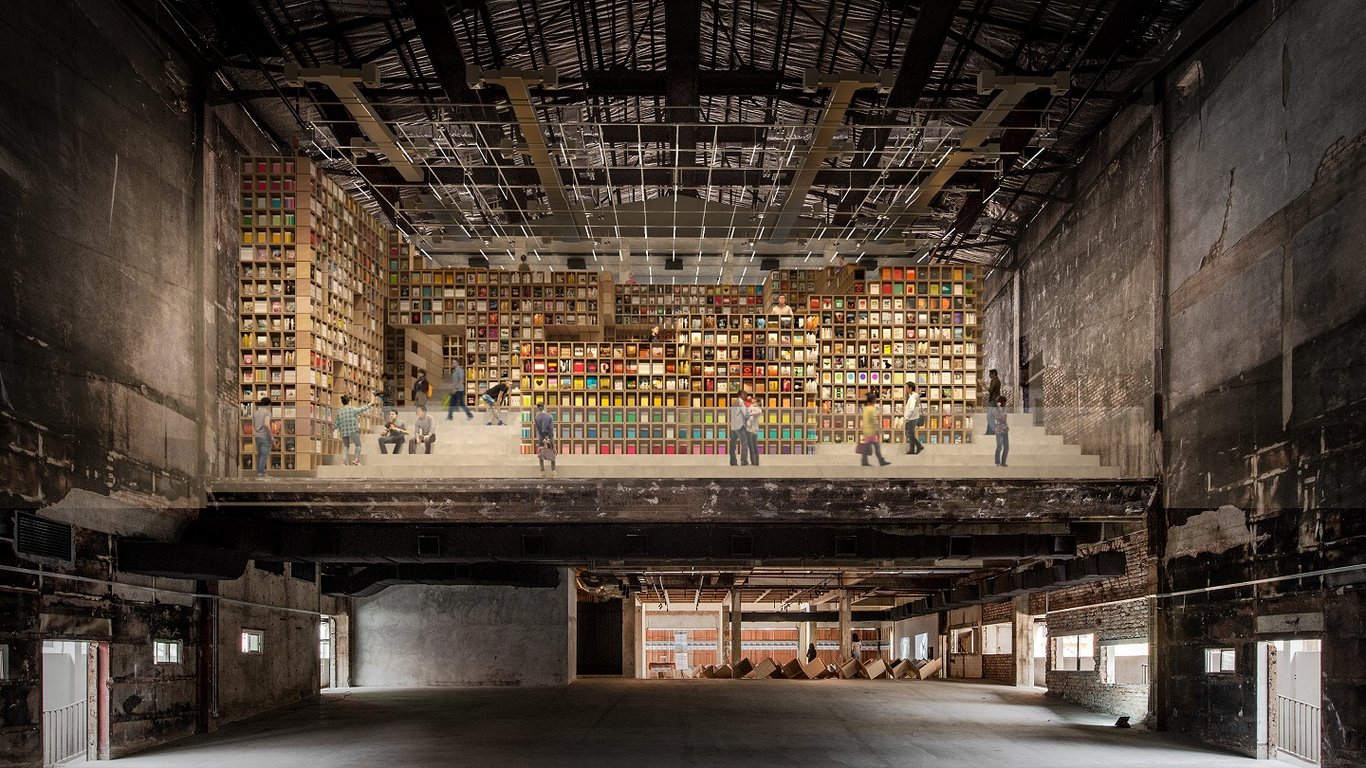

In the 2015 video installation Chimeric Landscape, evolving topologies emerge out of blots of ink, metaphorically transforming the substance into the legendary hybrid creature of the title, while Wall of Skies, an installation featured in the 2016 Shanghai Biennale, juxtaposes ink on paper with semi-reflective floors and custom slanted walls to create an ethereal, immersive experience that shifts according to each viewer’s vantage point. More recently, for “I Look for the Sky,” a 2020 solo exhibition at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum, Zheng presented an installation of the same title, using transparent textiles and acrylics to alter light conditions in the museum and craft a quasi-virtual space in which visitors could imagine new possibilities.

Speaking on the occasion of the exhibition, Zheng commented, “Sometimes I use the words ‘living paintings’ […] I look at this entire process of building this work, constructing this work [as] a process of how to sort of treat the light as a really living form.” It seems fitting that for Zheng, even a bracingly contemporary art installation links back to painting, and with it, an approach towards perspective shaped by New Materialism merged with Daoist convention, all reflecting the philosophical underpinnings of his work.

Banner image shows I Look for the Sky (2020). All images courtesy Zheng Chongbin.